Art that speaks a new language

Updated: 2016-02-26 08:59

By Mei Jia(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||

|

|

Some critics say Lao Shu's paintings have the same patterns as ancient masterpieces, but others argue that his mastery of photography and graphics make his works seem alive

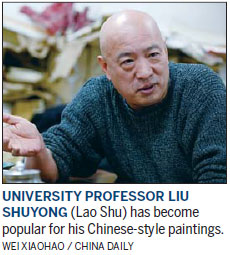

Liu Shuyong is a university professor specializing in Chinese language and literature.

But he is famous for Chinese-style paintings and photography. He is better known by his pen name, Lao Shu.

Now, a French firm is publishing a collection of his works.

His signature image, of a man in a Chinese long gown wearing a Western bowler hat and lacking facial features, has gained him more than 1 million fans on Sina Weibo, China's answer to Twitter, since he started posting his work online in 2011.

Each work is accompanied by a short poem.

His works cover subjects like the Monday syndrome, waiting for the annual bonus, and being bored of checking WeChat updates.

Critics and fans say his works offer new perspectives and help ease the stresses of modern living.

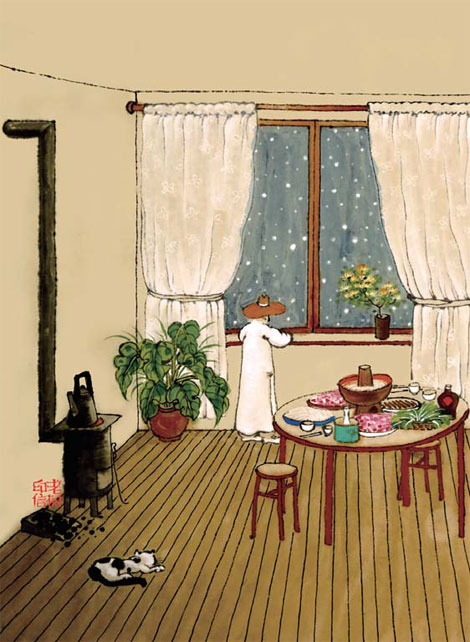

In his works, Liu's main character is Mr Long Gown, and his works portray him in various situations - in the mountains or among flowers, or even hugging a big fish.

His works show his main character against a backdrop found mainly in traditional Chinese landscape paintings, and include everyday elements and flourishes of modernity - from high-speed trains and ladies' lingerie to submarines and a dinner table scene, all drawn using a brush and ink.

"Nothing is impossible for me. There is too much confinement in real life, so why not be true to your heart and be free about time and space on paper," he says in his office and workshop at the Central University of Finance and Economics in Beijing, where he teaches.

The room is piled high with paper, most unlike the neat and Zen-like spaces he creates in his works.

The only clues to his art one finds in his room are scattered ceramics with either the dried or fresh plants that dot his drawings.

When he speaks, his language is peppered with expletives and academic terms. Somehow he does not sound impolite, but exudes a sense of humor, like he manages with the rhymes of his poems.

As for his popularity, Liu's works were shown on CCTV's annual Spring Festival Gala in 2015. He also held an exhibition of his paintings under the name Fun last year.

In January, online giant Tencent and China Publishing and Media Journal listed his book, An Inch of Spare Dreams, as the top original Chinese title of 2015, based on professional recommendations and readers voting online.

Liu Lihua, an editor with the book's publisher, New Star Press, says the title was popular beyond expectation given its price of 300 yuan ($46; 41 euros).

The press is reprinting the book as the first print run sold out shortly after being released in October.

Meanwhile, other publishers are pursuing him because some of their editors are longtime fans, as in the case of Wang Jiasheng, an editor from Guangxi Normal University Press that published another of his books, Zai Jiang Hu, in July.

"I use Lao Shu's works to take a breather when I am busy. His words and paintings are a cure for urban solitude," says Wang.

Some critics say his paintings are much like ancient masterpieces, with drawings, poems written in calligraphy, and signature seals, but art critic Zhong Ming says they are different "both because of his mastery of photography and graphics, which make his works alive and unique".

Liu, born in 1962 in a village in Shandong province, is also an established photographer and curator.

Speaking of Liu, Edward L. Davis' Encyclopedia of Contemporary Chinese Culture, published by Routledge in 2011, says: "Focusing on ordinary people - workers, peasants, and teachers - Liu is concerned with extraordinary themes - death, sex, ruins, social crisis - through a representation of non-dramatic, everyday-life-like images."

As Liu says: "When I'm drawing, my eyes drift apart from my body. I'm actually observing behind the lens.

"Cameras overcome the limitations that our ancestors had, enabling me to look at things from various angles, including from space."

Liu, who graduated from Tianjin's Nankai University in 1983, where he was attracted to traditional Chinese paintings, took up his job at the Central University of Finance and Economics' Chinese Language Department "as the capital offers more chances for art exhibitions".

"I was drawing like crazy in my university days, mimicking masters like Qi Baishi," he recalls, adding there was only one desk in the dormitory, so he had to seize the nights and noon breaks to practice drawing.

He says he took a break in 1986, because although "I can draw beautifully, I could not find my own style".

It was only in 2007, when he was looking after his sick father, that he picked up painting again to deal with insomnia.

"When I found that I did not need to prove myself to others anymore, I could find my own style," he says.

Describing his works, he says: "I paint for fun, and I don't take it really seriously."

meijia@chinadaily.com.cn

'I am true to my everyday anxieties'

Q: You mentioned that, at first, there were voices saying you don't know how to paint?

A: They were just judging me from their own experience and knowledge. When they put you inside their regime, and you do something that's beyond it, they say you're bad at it. It's the same problem for a man and a woman madly in love, who are zealous about turning "you" into "me".

So I always hate to judge good from bad. Instead, I prefer talking about yes or no. For me, artistic endeavors are creating yes from no, or we say, from "there isn't" to "there is". But showing off what you consumed at luxurious restaurants or what handbag you are carrying on WeChat? It's talking about "there is" from "there already is".

Q: How about your early education in art?

A: There was no art education for a village boy who was struggling with finding enough to eat. The only connection was the big-sized calligraphy that the old gentlemen in schools ordered us to practice in grades three or four.

A difficult childhood left many traces. I know how to save money and things and got used to that. For example, if I'm drawing on a piece of rare, high-quality paper, I feel reluctant. And after hours of hard work I finally ruin the precious paper. It's always on a random cigarette box, or delivery box, that I do my best works after a burst of inspiration.

Q: What is it in your paintings and verses that hit the softest point of each heart? Why do they touch so many?

A: I'm true to myself, without any disguises and pretending. I'm true to my everyday anxieties, too. If I feel horrible about going back to work on Sunday night, I express it.

Besides, for my teaching career, I've been on a long path of re-education, during which time I came to understand more about our past and present. Traditional Chinese verses were based on an agrarian culture, but we're using them to describe a busy urban life.

One of my merits is that I have been in vast rural lands for many years. So I kind of can bridge the two clashing cultures. I understand the group of people that curse the big, evil cities but at the same time refuse to leave and go back to their villages.

Q: How did Mr Long Gown, with no facial expressions, come into being?

A: First, he does have facial expressions. I was looking after my father after his operation to treat gastric cancer in 2007. Though I always slept well earlier, I couldn't sleep for days during that period. So I grabbed a piece of paper, and there he was. I guess then that I was too submerged in studies of the Minguo period (1912-49) to clothe him naturally in the outfits of the period.

Later, I found that it was OK and even better if I drew him without eyes, a nose and a mouth.

Today's Top News

Points of view

Small island makes a big difference

Rubio, Cruz gang up on Trump in debate ploy

'Invented-in-China’ products to the fore at MWC

Beijing edges NYC as home to most billionaires

110,000 refugees, migrants reach EU by sea in 2016

Tech giants reveal 5G innovations in Barcelona

Mechanism to be built to monitor ceasefire in Syria

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|