Another one on the way

Updated: 2014-02-14 08:47

By Joseph Catanzaro, Yan Yiqi and Li Aoxue (China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

|

Childhood antics in Taizhou, Zhejiang province. About 20 million Chinese couples are eligible for a second child under the new family planning policy. Provided to China Daily |

|

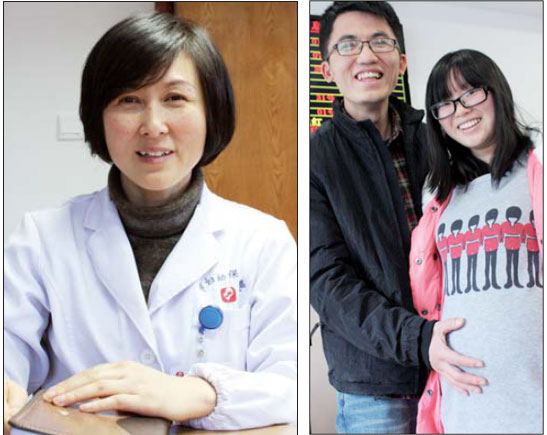

Left: Mao Yafei, vice-dean of Zhoushan Women's Hospital. Right: Le Zhangfeng and Zhou Na in Zhoushan are expecting their second child. Joseph Catanzaro / China Daily |

The recent relaxation of one-child policy has huge demographic implications for China and the world

In an unremarkable hospital waiting room on the island city of Zhoushan, Le Zhangfeng places his hand on the protruding curve of his wife Zhou Na's stomach and flashes an expectant father's proud smile.

"This will be our second child," he says.

Those simple words, so frequently uttered elsewhere in the world, have a special gravity in China. In a nation of more than 1.3 billion people, where for almost 40 years more than 60 percent of the population have lived under the one-child policy, Zhou's unborn baby is the harbinger - perhaps even the very first - of a new generation of second children who will be born under China's recently-relaxed family planning rules.

Le, a tall and quiet 31-year-old real estate agent, seems unconscious of the broader implications the birth of his new son or daughter will represent.

"We just love children," he says. "I think the more the merrier."

But in the halls of power in Beijing, and in the boardrooms of big business, the gentle bulge pressing against the front of 23-year-old Zhou's shirt represents more than just another new life.

Through a series of exclusive interviews and new figures obtained from government officials on the ground, we present the first glimmers of an answer to the question that has captivated the world: Will Chinese couples have a second child, now that a huge number of them can?

China's maternal predilection is not just a domestic issue.

The birth rate in the world's second-largest economy is tantamount to the tip of a demographic iceberg that afftects not just China's fortunes.

Indeed, for businesses and entire economies around the globe, Chinese babies and balance sheets have become inextricably linked.

The family planning policy, rolled out across the nation in the 1970s in an effort to speed development and increase per capita income, is estimated to have prevented some 400 million births at a time when it was reasoned China could least afford them.

But in 2012 the world's most populous nation saw an alarming decline of 3.45 million working-age Chinese, the result of a plummeting birthrate and rapidly aging population. Predicted to continue falling for the next 20 years, economists and demographers warn the shrinking number of workers will stunt growth as a shortage of labor sparks wage rises and inflation that drives businesses to cheaper pastures.

Currently, about 14 percent of the population has reached or passed the male retirement age of 60, and conservative projections suggest that by the early 2030s, about 400 million people - almost a third of China's population - will fall into a demographic of people aged 60 years or older that will be roughly equivalent in size to the population of the United States.

Wang Pei'an, deputy director of the National Health and Family Planning Commission, says China's working-age population will fall by an average of about 8 million people annually from 2023 as the aging problem continues to grow.

The latest census figures, from 2010, show there is now an average of 1.54 births per Chinese woman, well down from the estimated six children per woman in the early 1970s, but also below the replacement rate of 2.1 percent.

For China's manufacturing and export-based economy, these combined factors present a serious threat to future prosperity. And unlike the plethora of other countries - including Japan and South Korea - that are also grappling with declining births and aging, China is getting old before it has reached its prime.

Kerry Brown, executive director of Sydney University's China Studies Center, is unequivocal in his assessment of the problem.

"The scale of it is extraordinary, and the speed of it. It's kind of like a meteorite striking the planet."

It's already evident that a change in China's fortunes can produce an economic butterfly effect. A recent flutter in Australia's under-performing manufacturing sector, reported by HSBC, caused the Australian dollar to slump from 0.8836 to 0.8793 in January. It is a minor, but telling, example that the trade and investment links tethering nations and companies to China can just as easily become anchor lines to pull them down.

Brown says the erosion of China's working age demographic will create a labor supply problem that will have "an inflationary impact on Chinese, and therefore global, wage levels".

A world away from the debate about demographics and possible ramifications, on Nov 19, Le and Zhou received some welcome news.

In a major policy shift, the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China announced an estimated 20 million couples would be eligible to have a second child, providing at least one parent had been an only child.

And in the wake of that decision, Le and Zhou's relatively sleepy island home of Zhoushan became the very first region in China to implement the new policy.

For the couple, the flurry of speculation and opinion about whether the policy change would address China's demographic woes was superceded by the fact it had provided the solution to a more immediate and personal problem: Zhou's accidental, but welcome, second pregnancy.

Instead of facing a crippling fine for breaching family planning rules, Zhou is now six months along.

Her unintentional head start puts her in a very small group of pregnant women whose newborn could be the first delivered under the new policy, nationwide.

"I feel really lucky to be qualified for the new policy," Zhou says. "There are people I know who want a second child but don't qualify."

Located just off the coast of East China's Zhejiang province, Zhoushan is the largest island metropolis in the sprawling Zhoushan archipelago.

With a population of about 970,000, spread primarily across 12 of the more than 1,000 islands in the chain, it is considered sparsely populated by Chinese standards.

In 1841, British officer Captain Charles Elliot was severely reprimanded for giving up the then captured island of Zhoushan in a deal under which the trading empire took possession of what was seen as a lesser prize, a "barren" backwater named Hong Kong.

These days, Zhoushan is a popular holiday destination, a lively trading port and a marine industry hub.

It is also a demographic time bomb.

Today's Top News

Germany, France eye new data network

No much progress in Syria peace talks

Lantern Festival fires kill 6 in China

China urges US to respect history

KMT leader to visit mainland

11 terrorists dead in Xinjiang

Illegal detention reports probed

4 die in Austrian train-car crash

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|