It takes two to tango

Updated: 2011-10-28 09:26

By Wang Chao (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

Huge potential of co-productions attracts global filmmakers to China

For several years, despite its rich promise, China never figured prominently on the agenda of global filmmakers and distributors as the path to success was riddled with obstacles like strict regulations, piracy and a not too receptive audience.

| ||||

Not only has China become a market that commands the attention of buyers and sellers, but also an integral market in box-office returns for global film companies.

Industry sources say that China could surpass Japan and India in box-office receipts next year to take the second position globally and pose a strong threat to market leader US by the end of the decade. Lending credence to these claims are industry growth rates in excess of 64 percent and collections of over $1.5 billion (1.1 billion euros). Rough estimates for 2011 indicate that the industry could end up with receipts of over $2 billion.

During the past five years, domestic box-office revenue has grown by nearly 400 percent to 10 billion yuan ($1.57 billion, 1.13 billion euros) in 2010.

By current estimates there are more than 6,000 movie screens in China and another 20,000 will be added in the next 20 years. With such huge growth potential in the offing, there is no doubt that every filmmaker worth his salt wants a slice of the China pie.

Yu Dong, president of Polybona, one of the biggest film distributors in China, feels that box-office receipts could grow by another 15 billion yuan, as there are still more than 2,000 counties with no cinemas.

Teaming up

When Italian director Bernardo Bertolucci made his Academy Award winning film The Last Emperor on the life of the last imperial Chinese ruler Aisin-Gioro Pu Yi in 1987, he became the first foreign director to co-produce a film with Chinese partners.

However, the Chinese participation in the movie remained limited to some Chinese actors and actresses, without any real involvement in the story or other technical aspects.

While the film brought several accolades to Bertolucci, for China it was the first taste of Western filmmaking and filmmakers. Though The Last Emperor was screened in China in 1988, it did not make much in terms of box-office receipts.

While Bertolucci made the initial sorties, in 2011 the Chinese film industry has now become the calling card for big-ticket co-productions.

Wendi Deng Murdoch, the wife of newspaper baron Rupert Murdoch who owns the global film house 20th Century Fox, teamed up with a group of Chinese investors to produce the 2011 movie Snow Flower and the Secret Fan.

Since 2009, the number of co-productions with China has risen to 60 on average every year, a year-on-year growth rate in excess of 10 percent. In 2011, the growth rate is expected to surpass 30 percent, according to China Film Coproduction Corp (CFCC), which is responsible for co-production filings.

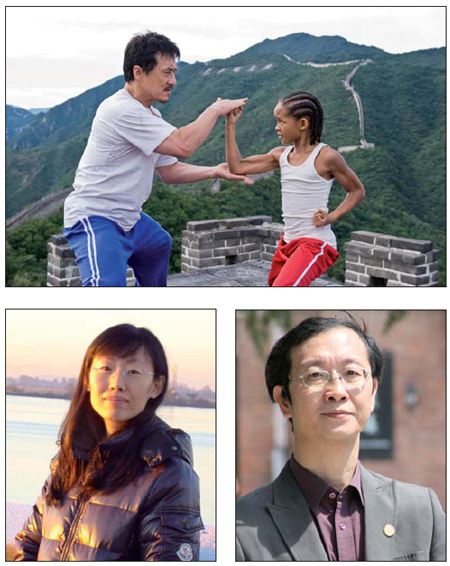

Co-produced films such as The Karate Kid released last year have brought big bucks to its investors. The film, co-produced by Columbia Pictures and China Film Group Corporation, cost $40 million to make and has so far earned $359 million worldwide.

"Making films in Hollywood is becoming more and more difficult as US film studios are getting increasingly worried over failures," says Dany Wolf, executive producer of The Karate Kid.

"The cost of making films in Hollywood is far higher than in China and the marketing costs for some moves can outstrip even the production budget.

"China's long history and rich literature is full of amazing stories that would make wonderful films. I am reading books and screenplays and constantly looking for new films ideas," he says.

Thrilled by the success of The Karate Kid, Wolf says he is planning other co-production ventures in China to create exciting films that will appeal to Chinese, US and global audiences.

"The future of Chinese cinema is very bright and co-productions are the key to making that light shine around the world," Wolf says.

It is not just the Chinese element that is drawing foreign directors to Chinese shores, says Shi Nan-Sun, a Hong Kong-based producer. She says the real motivator for most foreign filmmakers to come up with co-productions is the higher revenue realization.

According to regulations passed by the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television, an imported Hollywood blockbuster can get only 17 percent of the box-office revenue from China, while co-productions can get as much as 30 percent to 40 percent.

"Everyone is jumping on to the bandwagon," says Hong Kong-based producer Bill Kong. Kong co-produced the 2000 hit Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, directed by noted Chinese director Ang Lee.

"Ten years ago if you made $3 million in China you would be jumping up and down, today it's more like one or two hundred million," Kong says.

US-China co-production films such as The Forbidden Kingdom and The Mummy: Tomb Of The Dragon Emperor, released in 2008, got global returns of $120 million and $400 million respectively. Notably, the films, while incorporating Chinese elements in the story, had US directors at the helm.

Quota muddle

While no one doubts the huge potential of the Chinese market, the major hurdle for most filmmakers is the import quota system whereby screenings of just 20 big-ticket foreign films are permitted every year. To some extent that also explains the reason why most of the global players are keen on co-productions.

Under the quota systems foreign filmmakers need to share box-office revenues with Chinese distributors such as China Film Group Corp, and the cinemas. After fees and taxes, the share foreign producers get is roughly around 13 percent to 17 percent.

Another 20 to 30 overseas films, or "flat-rate films", usually with less potential to sell as many tickets as the "revenue-sharing" ones, are bought by Chinese distributors at international film festivals. The Chinese distributors, however, hold exclusive screening rights for the movies in China.

Compared with the 4,000 films produced worldwide every year, the 40 to 50 foreign films allowed in China is just a meager number, meaning nearly 99 percent of the global films are locked out of the Chinese market.

Ten years ago when China signed the WTO agreements, the government made a promise that it would drop the import quota on films in 2011.

"Though theoretically there is no import quota after 2011, foreign films still have to go through the censorship laws of the Chinese government," says Yin Hong, associate dean of the School of Journalism and Communication, Tsinghua University and an expert on the Chinese film industry.

"Co-production is a good way to bypass the quota system and even censorship in China," he says.

Yin feels that the cooperation route is also a strategic consideration for foreign filmmakers as Chinese policies are far more unpredictable than those in the US and European markets. "By partnering with Chinese film companies, foreign companies can avoid most of the regulatory problems."

Deng Meng, director of cooperation and contracts at China Film Group Corporation, says foreign film studios did not realize the importance of the Chinese market until the success of blockbusters such as Avatar and 2012.

"Distributors never thought that China could surpass Germany, France and Japan, and become the largest overseas market in terms of collections for Avatar, behind North America. That's why the crew of Transformers: Dark of the Moon flew to China specially to promote the film earlier this year."

After Bertolucci, co-production of films went into hibernation until the 1990s, when the TV series Shaolin Temple was shot in Henan province along with Hong Kong partners. But at that time, policies towards partners were very stringent and the Hong Kong side had to revise storylines and characters in accordance with mainland requirements.

The real surge for co-production of films started in 2004 when the government lowered the standards. Under the norms, for co-production films, only some scenes need to be shot in China, while Chinese actors/actresses should make up just one-third of the star cast. Adherence to these norms helps the movie to be classified and screened as a domestically produced venture.

Europe connection

Besides co-producing films with Hollywood, China has also teamed up with filmmakers from the United Kingdom, Italy, New Zealand and Australia. But most of the co-production ventures are still between mainland and Hong Kong filmmakers. Foreign partners only account for 10 percent to 20 percent of the total, although the number is growing quickly.

"The worldwide trend is co-production, since films are essentially international products," Yin says. "Nowadays most Hollywood films are co-produced. By this way it can also take advantage of local resources like distributors and cinemas."

With co-productions surging, some foreign companies are not just satisfied with individual alliances and rather prefer to establish joint-venture companies that are dedicated to co-production films in China.

|

|

In August Hollywood production house Legendary Entertainment teamed up with Chinese media company Huayi Brothers Media Corporation to set up Legendry East. The two companies said in a statement that the new venture will produce English films that draw on Chinese ties.

During the same month, another Hollywood company Relativity Media LLC signed an agreement with SkyLand, a China-based production venture, to release several Relativity films including Immortals and a fairy tale about Snow White starring Julia Roberts.

Experts compare this move to "moving the Hollywood school to the front door".

"We can learn mature production systems from Hollywood and other Western film companies," Deng says. "For example, Hollywood has a very clear division of script writers - some write dialogues and some write stories. But in China, these career paths are not clearly defined. I am confident that gradually we will also pick up these nuances."

Huge potential

It is not just the big studios that are in the China film mart. Several small and independent producers are also vying with each other to grab a slice of the huge pie.

Former journalist Richard Trombly was one of those who decided to leave his fourth estate career for a stint with the camera. Starting off as a scriptwriter, he launched his movie career with a co-production called Waiting in 2008. The film narrates the stories of left-behind children of migrant workers in China. The film was screened at various film festivals and then sold to a foreign website.

"Thousands of independent foreign filmmakers like me are making co-production films in China," he says. "We don't think the mainstream market here will accept our work, plus I don't have the money, like the big studios have, to promote it. So most of the time I sell my work to the foreign market. If it receives good comments or wins awards, they can be brought back to China at a flat-rate."

Trombly, however, says that he is not sure whether co-production films will win in both the foreign and the Chinese market at the same time, be it the small-budget films or Hollywood blockbusters.

"There are so many restrictions - you cannot touch some topics, and you are not allowed to show bloody scenes or nudity, which can prove fatal for many films."

For such films the only route left is the string of film festivals across the world.

How to cater to audiences in both markets is an issue that even big filmmakers are grappling with. Due to the cultural disparity between the East and the West, many producers find it hard to win both the markets, even though the film is co-produced.

An example of this is The Karate Kid, which earned just $7 million in China, less than 1/20 of the earnings in North America. "You cannot assume that an idea or story that was successful in the US will always be successful in China," says Wolf.

"The Chinese audience is sophisticated and does not accept that a young foreign boy can be bullied around by a group of Chinese students. The plotline of bullies beating a new student worked well in the original film but unfortunately it does not translate smoothly into Beijing settings."

Wendi Deng Murdoch also admits that it is hard to attract audiences from different cultural backgrounds - the $6 million budget Snow Flower and Secret Fan earned just $1.35 million in the US and $302,258 outside of the US, says Box Office Mojo, an online box-office database affiliated to IMDB.

Experts also suggest that having co-production should not just mean Chinese scenes or several Chinese characters. "It should be much more than that," says Zhang Xun, managing director of CFCC.

"We received some scripts which are totally Western-oriented. They just changed the foreign character into a Chinese face and obviously had no idea of Chinese culture. Such plots do not go down well with Chinese audiences."

Deng also echoes similar views. "The Chinese market has its own characteristics. For example, there is no rating system in the market, so it is inappropriate to screen bloody and adult content to some audiences. If the foreign partners really want to make profit in China, they must adapt to the situation."

|

Clockwise from top: A scene from US-China co-produced The Karate Kid featuring Jackie Chan; Yin Hong, associate dean of the School of Journalism and Communication, Tsinghua University; Deng Meng, director of cooperation and contracts at China Film Group Corp. Photos Provided to China Daily |