Chinese skilled laborers look overseas

Updated: 2014-01-03 10:00

By Zhang yuchen (China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

Many blue-collar workers hope to emigrate, but admission policies are being tightened

Before he emigrated to Australia in 2005, Yin Fagang was a migrant worker in Shenzhen, a coastal city in the south of China. The quality of his welding work was so high that some foreign colleagues urged him to emigrate to Australia, where there were opportunities aplenty.

As a result of their prompting, Yin, who now lives in Perth in Western Australia, was one of the first of many hundreds from Xiaoli, Shandong province, to emigrate - about 1,000 skilled workers followed him to Australia between 2005 and 2007. At the time, the immigration quota was generous and authorities were relaxed about admitting people with a comparatively poor grasp of English.

Today, however, there is a labor surplus in many developing countries and a lack of workers in developed economies. That imbalance has forced politicians to tighten immigration regulations and quotas, making it harder for skilled workers to flow freely between countries.

The intense international competition for workers has resulted in countries devoting a great deal of thought to how to attract the most talented individuals, from skilled workers to wealthy investors.

In Australia, the immigration policy for 2013-14 will allow roughly 190,000 people into the country, two-thirds of them skilled workers. Meanwhile, in Canada, the policy for skilled workers has been amended and the annual quota has been reduced to a mere 5,000, with applications for each eligible occupation capped at 300. However, the immigration trend globally has become more complicated for low-end workers.

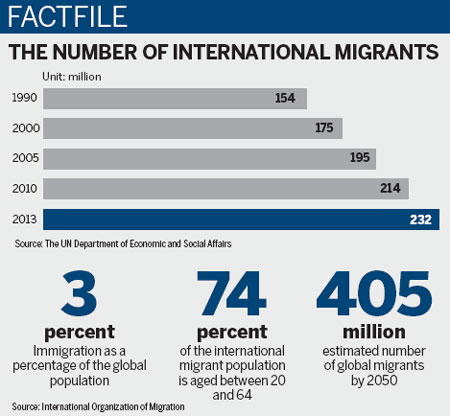

In 2012, about 13 percent of the global adult population, approximately 63 million people, was willing to up sticks and move overseas as permanent residents, according to a poll conducted by Gallup.

Asians form the largest single group among the world's migratory labor population, according to John Wilmoth, director of the Population Division at the United Nations' Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

Currently, approximately 19 million Asians are resident in European countries, while there are 16 million living on the North American continent and 3 million in Australia. Moreover, around 19 million Chinese would like to choose the US as a destination.

At the same time, Asia itself is seeing huge internal labor flows as a result of the continent's economic rise since 2000.

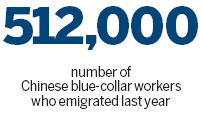

Although a large number of Chinese emigrants are high-level professionals and investors, skilled blue-collar workers are also in great demand. Last year, 512,000 of them left China to seek work overseas.

"There is global competition for a limited pool of talent. Countries are increasingly in competition to attract the best migrants via preferential visa regimes, fast-track settlement options and other methods," says Khalid Koser, deputy director and academic dean at the Geneva Centre for Security Policy.

While the big picture shows that specific immigration policies have been amended to take domestic labor markets and the international economic environment into account, the most popular destination countries have been tightening immigration measures.

In July, Australia revamped its immigration policy for skilled workers policy and reduced the number of skill categories for temporary visa applications - known as Subclass 457 visas - to 187, around one-third of the previous number.

The 457 visa allows skilled workers to travel to Australia - which absorbs the largest number of skilled global talent every year - and work in their nominated occupation for an approved sponsor for up to four years. It has traditionally been the easiest visa for new immigrants to obtain and from February 2012 to February 2013, 107,500 people from across the world were granted a 457.

Among those 187 categories, around 40 are related to skilled blue-collar employees, such as pipeline workers, welders and carpenters. Every year, millions of blue-collar workers leave China. While the fact that they start work earlier than their foreign counterparts means that they usually have greater work experience, their language skills are often poor. In July 2009, the Australian immigration department raised the bar in English language skills.

The problem is not how many people want to emigrate, it's how wide the door will be opened for the free flow of immigrants, says Mei Xinyu, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of International Trade and Economic Cooperation, quoted by China News Agency in May.

In 2005, Yin Fagang paid an agency 120,000 yuan ($19,800; 14,400 euros) to deal with all the matters arising from his visa application. By 2007, when the last batch of skilled youngsters left Xiaoli and set off overseas, the agent's fee had risen to 150,000 yuan.

The Australian government recently reached an agreement with China to regulate agents dealing with visa applications for skilled blue-collar workers. A detailed list of agents and the issues in which they will be allowed to intervene will be finalized in the near future.

Most skilled Chinese workers in Australia live in the west of the country and earn an average A$800 ($716; 516 euros) per week. However, their lifestyles are not much different from when they lived in China; they generally keep to themselves, eat Chinese food and watch satellite TV channels to maintain contact with their home country.

"On the whole, skilled migrants live safely in good conditions," says Koser.

"The exceptions are those working in unstable countries or countries affected by natural disasters, but their employers usually insure them well."

Under the "10-pound Poms" policy inaugurated after World War II, Australia offered assisted passages to around 1 million British immigrants who were willing to move and help reduce the labor shortage in the "Lucky Country". However, the most recent flow of international immigration has seen prosperous Chinatowns springing up across the world in the past decade or so.

Li Guilan's son Wang Qingkui moved to Australia in 2007. Like Yin before him, Wang is a welder and lives in Perth. Li says her son has plenty of Chinese neighbors, but they don't mix much and there's no indication of a cohesive Chinese community in the city.

"We didn't talk too much," says Li, 60, who had just returned to her hometown of Chuzhuang in Xiaoli after a 12-month visit to take care of her newborn grandson, an Australian citizen by birth. "However, the locals said hello to me. I couldn't understand what they said, but I recognized the welcoming smiles on their faces."

Because many countries have amended the bureaucratic obstacles to skilled immigrants gaining entry, the main challenges are now social and cultural and mostly center around quality of life and schools for the children, says Koser.

For Mei Xinyu, those issues mean that modern international migration management will become essential in the years to come, and NGOs will be deeply involved in the process.

"Cultural conflicts and risks are unavoidable, but they can be dealt with in the long run," he says.

Li is unsure if her son will stay in Australia permanently. After six years working for a number of employers, Wang has bought a house. But he is wary of applying for permanent residence, which means he has to give up Chinese nationality, but he may wish to return to China later in life.

"With the blue skies and clean air, the environment in Australia is really good - but who really wants to live and work so far from home?"

zhangyuchen@chinadaily.com.cn

|

A resident of Xiaoli town, Jinan, capital of Shandong province, talks online with a relative in Australia. Many young people from the town have emigrated. Chen Ning / for China Daily |

|

A worker learns how to weld at a boiler factory in Xiaoli. The factory is one of the town's main bases for the training of blue-collar workers. Provided to China Daily |

|

Li Guilan has just returned to Xiaoli after a 12-month visit to Australia, where she looked after her newborn grandson. In 2007, Li's son moved to Perth to work as a welder. Zhang Wei / China Daily |

(China Daily European Weekly 01/03/2014 page24)

Today's Top News

Merkel fractures pelvis skiing, cancels visits

Portugal declares three-day mourning for Eusebio

Forbidden City to be closed every Monday

Icebreaker prepares for breakout

Beijing rejects Abe's call

Illegal ivory stash destroyed

Israeli ex-PM Sharon's condition in steady decline

Yahoo says ads in Europe spread malware

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|