She followed her heart

Updated: 2016-06-10 08:34

By Yang Yang(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||

Yang Jiang will long be remembered for her witty writing and translations, but her independent outlook may be her greatest legacy

Among all the apartments in the 19 three-story buildings near Yuyuantan Park in Beijing, only one has maintained its original look, with neither interior decoration nor the balcony enclosed with glass.

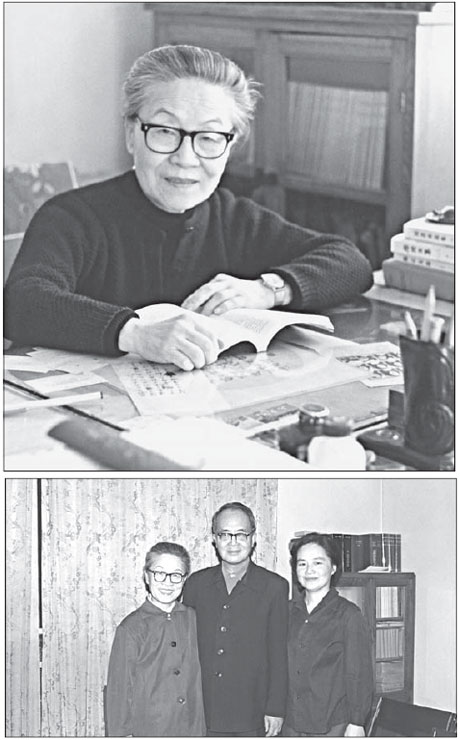

The apartment in Nanshagou Community, where the famed Chinese writer and translator Yang Jiang lived until her death on May 25 at the age of 104, is typical of her modesty. The space is almost unadorned - white walls, cement flooring, an old-fashioned sofa and desks worn by years of use.

|

|

Yang and her equally famous husband, Qian Zhongshu, moved into the unit in 1977, just after the "cultural revolution" (1966-76). But Yang lived there alone for nearly two decades after the deaths of Qian and their only daughter, Qian Yuan. While the couple had become household names in the 1980s, they were always indifferent to fame or wealth, and few reporters or readers visited them.

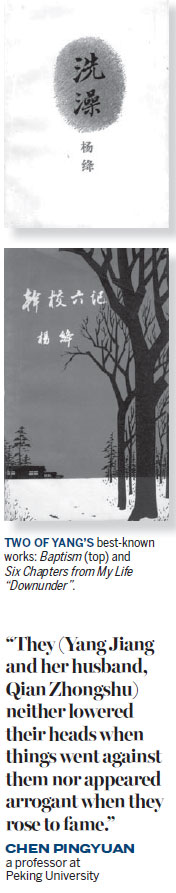

Known for her subtle and witty writing style, Yang wrote her first play in 1941. A prolific writer, she became famous for her novels, essays, plays and translated works. Her most popular novel, Baptism, was translated into English, French and Italian. It depicts a group of intellectuals from the old society adjusting to a new one in the early 1950s.

Yang never stopped writing. At 94, she started writing a book, Walking onto the Brink of Life, to reflect on her life. It won China's top book award in 2007. At 100, she was still writing articles for newspapers.

Qian Zhongshu, meanwhile, was a scholar and author of the best-selling novel Fortress Besieged.

In 2001, on behalf of her family, Yang set up a scholarship fund at Tsinghua University, where the couple had studied and worked, to encourage students, especially those from poor families, to read. They donated all their royalties, which totaled more than 24 million yuan ($3.6 million; 3.3 million euros) over the years.

Chen Pingyuan, a professor at Peking University, remembers a woman whose achievements had come despite the turmoil of the collapse of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), China's civil war and the "cultural revolution".

In an article mourning Yang, he writes, "The older generations had experienced much fiercer waves, but many of them stood up. They read books out of interest, were led by their hearts, and never followed the stream. Although they had to compromise to some extent, they kept their honesty, which is not really easy."

Born Yang Jikang in 1911, the year China's feudal empire collapsed, she faced tough years before and after the founding of New China. Whether living in poverty or affluence, however, Yang always followed her heart, living a simple and honest life.

Yang was raised in a family of open-minded intellectuals. Her father, Yang Yinhang, a renowned wit and intellect from Wuxi, Jiangsu province, graduated from the University of Pennsylvania with a master's degree in law. The fourth daughter in the family, she, along with her sisters, were all sent by her father to good schools to receive a Western-style education. Later she would adopt the pen name Yang Jiang.

Like her father, Yang Jiang turned out to be a person of spirit, good at both Chinese and English. She had long known what she wanted - to study arts at Tsinghua University.

"Initially I chose arts because I was determined to read good novels from home and abroad to understand the art of fiction writing, so that I could write good fiction," she wrote in the preface to The Complete Collection of Yang Jiang.

Her happy marriage with Qian Zhongshu was another example of her free thinking and independence. The two bookworms met in 1932 at Tsinghua by coincidence and quickly fell in love. Their love never weakened. After getting married, in 1935 the couple went to Britain and studied at Oxford University, returning to China three years later.

By 1952, the couple was working at the Institute of Foreign Literature part of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

At that time, women in China started to wear Lenin-style clothes - gray double-breasted shirts and long trousers with a leather belt fastened around the waist, a symbol of the equality of the working class. Yang, however, still wore a slim qipao, took a rickshaw and held a parasol over her head.

During the "cultural revolution", many intellectuals were forced to "disclose" each other's "guilt". Yang, already denounced as a devil, was put on stage to face her husband's accusers. "It's not the truth! It's not the truth!" she repeated, stamping her foot, recalls Ye Tingfang, a researcher at the Institute of Foreign Literature.

In the late 1960s, intellectuals at the institute were sent to the countryside to work, and Qian and Yang, almost 60, were among them.

Yang later compiled her stories of that time into a book, Six Chapters from My Life "Downunder".

Lu Jiande, deputy director of the institute, says unlike other memoirs of the time, Yang's contains no complaint or anger. It was a difficult time for intellectuals, but he admires Yang for her positive attitude.

Yang spent her leisure time writing, and when Qian passed by, she would give him the work to read. Then, the couple would often sit, chatting and laughing, though there were plenty of serious moments, too.

During this time, their son-in-law committed suicide. In Six Chapters, Yang captures the event in a single sentence, but the sadness fills the page.

After Yang's translation of French writer Alain-Rene Lesage's Gil Blas into Chinese was well-received in 1956, she was picked to translate Don Quixote from Spanish. She began to learn the language in 1959, at the age of 48.

"They neither lowered their heads when things went against them nor appeared arrogant when they rose to fame," remembers Peking University's Chen.

"Such people deserve our younger generations' respect."

yangyangs@chinadaily.com.cn

Today's Top News

The can-do generation to the fore

Riding the wave

China lists first sovereign offshore RMB bond on LSE

British PM denounces Brexit's 'complete untruths'

47% of European businesses would expand in China

Xi urges Washington to boost trust

Council of Europe unveils security convention

Former PM warns of chaos in case of Brexit

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|