'Rotten legs': a lifetime of suffering

Updated: 2016-07-07 07:52

By Zhao Xu(China Daily)

|

|||||||||

Researchers say residents of villages in the provinces of Zhejiang and Jiangxi were probably infected with anthrax by the Japanese army during WWII. Zhao Xu reports.

Situated in the center of Quzhou, Zhejiang province, is the Quhua Hospital, affiliated with Quzhou Chemicals, one of China's largest producers of industrial chemical products. The hospital has a reputation for treating chemical burns. Zhang Yuanhai, a wound specialist and the hospital's deputy director, has personally operated on many of the patients with the condition.

"'Rotten-leg disease' - that's how it's known here," the 49-year-old said. "Our treatment basically has two stages. First, the ulcers on the patient's legs are thoroughly removed and the area is cleaned. All the relapses over time have produced a thick, hard layer of tissue, like a board, within the damaged area. This has to be thinned to prepare for the skin graft that usually takes place 10 days after the initial surgery."

Skin from the head is used for the graft. "Skin from the scalp is preferred because it's thicker, more elastic and easier to grow. This gives the skin graft a higher success rate," Zhang said. "It usually takes about a week for the skin on the patient's head to grow back together and repair itself."

Five months after surgery, 79-year-old Chen Chunhua was recovering well. But for her children, the memories are still raw. "At one time, my mother's legs were rotting so terribly that the bones were almost visible," said Zheng Zhongguang, 56, Chen's oldest son. "The rotten part, so unsightly as to be almost beyond description, reminded me of the dregs left on a millstone after beans have been ground."

For many years, Chen relied on a herbal remedy for relief, using leaves picked from the nearby mountains. In the 1980s and 90s, she twice sought a cure in hospitals in Zhejiang and elsewhere, but was told that the only possible solution was amputation. She baulked at the idea, resorting instead to regular injections of antibiotics to battle the constant inflammation and occasional bleeding.

When the nightmare began, Chen had no idea what was happening. "I remember noticing a little red dot on my left leg. It soon turned into an itchy but painless blister which, after some scratching, bled and burst to form an ulcer with a hard center," she said. "That was really the beginning of my ordeal. I was about age 6 or 7 at the time, and my job was to tend the cattle every day."

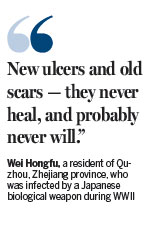

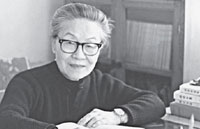

For Wang Xuan, a long-time researcher into the Japanese army's use of biological weapons during World War II, Chen's words were the key that opened a door into the darkest chapter in the contemporary history of Zhejiang and neighboring Jiangxi province.

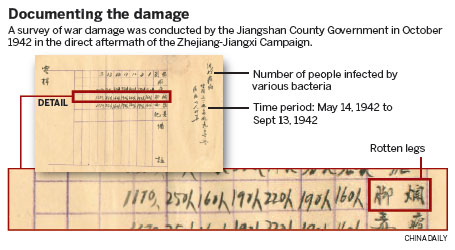

Between May and September 1942, Japanese troops launched a well-planned campaign against civilians in the two provinces as retaliation for a US Airforce bombing raid on Tokyo and other large Japanese cities.

The Japanese aimed to take control of the Zhejiang-Jiangxi Railway and also to destroy several airfields in the area that were used as Allied bases.

"Throughout the Zhejiang-Jiangxi campaign, the Japanese engaged in full-scale biological warfare. That operation was one of the largest germ warfare attacks they mounted in China during WWII, but there were also lots of ground troops," said Wang, whose interest in the subject dates back to 1994, when she was working for a company in the Kansai area of Japan and paid a visit to her hometown in Jinhua, Zhejiang.

"They used everything, from bombs containing germs and plague-infected fleas, to food and clothes carrying the same bacteria. The result was the outbreak of deadly diseases including bubonic plague, typhoid and cholera," she said.

Trail of devastation

By mid-August 1941, the Japanese, having accomplished most of their goals and lacking the troops to guard the entire region, began to move out. They left a trail of devastation.

"Locals who had gone into hiding in the mountains returned to their homes, only to discover little black or red dots similar to Chen's, usually on their legs. What happened in the following years was a heartbreaking yet familiar story in that part of Zhejiang. The cause of their suffering was a bacteria called bacillus anthracis, or anthrax," Wang said.

"Although ulcers were seen on other parts of the body, in most cases they appeared on the legs. That's because cutaneous anthrax, where the bacteria makes a breach through an opening in the skin, constitutes the most prevalent form of anthrax infection. Imagine a farmer working barefoot in the paddy fields of southern China - it would be virtually impossible for them not to have some minor injuries on their feet or legs. That's as true today as it was 70 years ago," she added.

"Compared with victims of bubonic plague, a large number of those infected with anthrax survived, only to live in an ever-worsening nightmare, that followed many of them into their graves, many years after the war. It's a nightmare for which no explanation has been offered, at least until very recently."

Eight years into her investigation, she took three internationally renowned scholars from the US to her hometown in Zhejiang: Sheldon Harris, author of Factories of Death, the definitive book about the activities of Unit 731; Michael Franzblau, professor of dermatology and medical ethics; and Martin Furmanski, a medical scientist of pathology and expert on the prevention of biological warfare.

Historical documents

Last year, Furmanski returned to China to deliver university lectures about rotten leg infection and Japan's use of germ warfare.

"There is ample historical documentation and epidemiological evidence to confirm that these attacks (using biological weapons) had occurred," he wrote in an email to China Daily. "The onset of this large body of rotten leg victims begins dramatically in the summer of 1942, with essentially none before that time."

According to Furmanski, although other conditions - diabetes and vascular diseases for instance - can also cause ulcers that won't heal because of poor circulation, they almost always occur in older adults, while almost all of the people with rotten leg ailments who are still alive were teenagers or even toddlers when they first developed the symptoms.

Reflecting on the fact that many people were infected not in the summer of 1942, but in the years that followed, Furmanski said: "This is not unexpected: anthrax spores can survive for many years in soil or on objects."

Over the past two decades, Wang and her team of volunteer researchers have interviewed more than 1,000 men and women believed to have anthrax. Most of the victims have since died. "One can only get a glimpse of their tortured lives through a few interview notes and photographs in our research database," said Wang, who has concentrated on raising social awareness of this "disease from history", as she calls it, and providing medical aid to patients.

Since 2014, when she began launching programs to help people with rotten legs, several hospitals in Shanghai have provided effective treatment - some for free - for elderly patients from Zhejiang, and moves are in progress to also help patients from Jiangxi in the near future.

In March last year, the 64-year-old launched a project to raise funds on the micro blog platform of Tencent, one of the world's biggest internet companies. So far, more than 1 million yuan ($152,400) has been collected. The money pays for treatment at four participating hospitals: the Shanghai Ninth People's Hospital, the Shanghai TCM-Integrated Hospital, the Quhua Hospital and the Jinhua Central Hospital. Some of the country's leading wound experts are also involved, providing the project with much-needed medical guidance.

"Zhejiang has a higher per capita GDP than France. The government should be doing more," Wang said.

The project started at the Quhua Hospital in September, 85 years after Japan invaded Northeast China.

"I can clearly remember a patient called Tu Maojiang," said Zhang, the head doctor at the Quhua hospital. "When I first saw him at the hospital, his wounded legs were wrapped in dirty cloths and cardboard. When he left the hospital a month later, having undergone the operation, he told me that for the first time in his life, he could wear leather shoes and visit his relatives," he said.

"Patients who have had the surgery must wear elastic bandages to increase blood flow. And to prevent a relapse, they must safeguard the healed wound from damage or contamination," he continued. "It still takes some time, a year probably, before we can declare victory."

Persistent memories

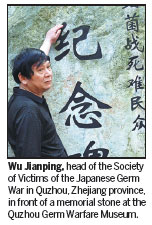

Since the start of the project, Wu has traveled around Quzhou trying to persuade people to visit the hospital. He said his biggest thrill came when he saw two men, both in their 80s, who were having their rotten legs treated. "They were walking towards the door at the end of the hospital's long corridor, arm in arm," said the 54-year-old, whose paternal uncle and aunt died from bubonic plague after an airborne attack by Unit 731's Biological Warfare Unit in 1940.

Dramatic and disastrous, the bubonic plague started in Quzhou, continued to spread across Zhejiang during the war and reached Wang's own village, Chongshan, in Jinhua, in 1942.

About 400 people - one-third of the village's population - was wiped out. "We all share the same surname," Wang said.

After seeing so many rotten legs, she still finds it hard to shake the memory of a man who had lost his legs. "I met him in 1996 in Yushan, Jiangxi, in a village near a wartime air base. He 'walked' up to me with his hands, his body supported by a wooden board. He told me that the whole village had rotted to death and he was the only survivor," she said.

"Once you see that sort of suffering, it's impossible to turn your back on the victims."

Contact the writer at zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

|

Xu Yusheng's legs began to rot when he was age 13. The 88yearold's left leg had to be amputated. Photos By Zou Hong / China Daily And Provided To China Daily |

|

|

|

Zhang Yuanhai, a wound specialist, inspects the legs of Chen Chunhua, who had an operation at the Quhua Hospital in Zhejiang in January. |

|

Wang Xuan visits patients with rotten legs at the Quhua Hospital in April. |

|

Following treatment on his rotten legs, 79yearold Tu Maojiang can finally wear leather shoes. |

(China Daily 07/07/2016 page6)

Today's Top News

Chilcot report: Iraq war based on flawed intelligence

UK invasion of Iraq was not last resort: Report

Berlusconi accepts Chinese offer for AC Milan

UK consultancy loses license, Chinese graduates being told to leave

Chinese online retailers offer 'Brexit sales' as sterling hits record lows

British PM race cut to 3 hopefuls

Suicide bombers hit three Saudi cities

Response to 'fully depend' on Manila

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|