From powerhouse to poor relation

Updated: 2015-08-13 07:52

By Zhou Huiying(China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

In the 1950s, coal miners earned high incomes and benefited from a raft of government welfare measures, so the job was popular among young people in Hegang. Today, the decline of the industry means fewer and fewer young people are staying in the city. According to data from the 2000 national census, the northeast region had the country's highest unemployment rate, with ex-miners accounting for the largest group of jobless workers.

"The pillar industries in the three provinces are strikingly similar and focus on the primary sector, including equipment manufacturing, petrochemicals and agricultural products," Feng Lei, an expert at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, told China Youth Daily in July.

"Given the industrial structure of the northeast, the decline in domestic investment and the drop in international commodity prices is bound to have a great effect on the three provinces, so it's no surprise they're experiencing an economic downturn," he said.

Feng said the region is being hit twice over because the depressed economy is accelerating the population outflow and the declining population is hampering economic revitalization efforts.

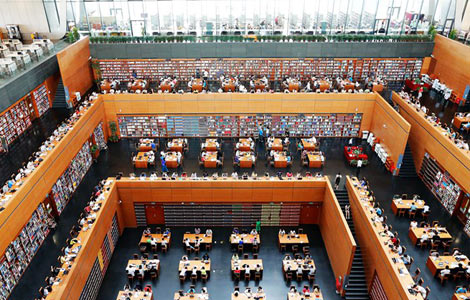

The regional economy isn't the only thing affected by the population outflow, and other areas, such as education, are also suffering.

Universities in the three provinces are experiencing a severe shortage of students. Last year, 28,335 graduates were admitted to 50 colleges and research establishments in Liaoning, 2,259 fewer than the total enrollment plan for the province, according to a report published by China Education Online.

Moreover, an increasing number of graduates from the three provinces are opting to move to southern cities in search of work. "This phenomenon is obvious at our university. Not only do students from the south choose to return to their hometowns, but more northeastern students are heading south because they believe the economically developed areas can provide more job opportunities," said Li Lianying, a teacher who works at the Employment Guidance Center at Jilin University.

Family matters

The effects of the outflow of labor and talent are being exacerbated by a falling birth rate. Data from the 2010 census show that the figure was 1.03 percent in Liaoning and Jilin, and 1 percent in Heilongjiang, well below the national 1.5 percent average, and lower than in Japan and South Korea. The UN's Population Division defines a birth rate below 1.3 percent as "ultra-low".

At the end of 2013, the National People's Congress, China's top legislative body, adopted a central government proposal under which couples would be allowed to have a second child if one of the partners was an only child.

Heilongjiang implemented the policy in April last year, but so far just 6,484 qualified couples, accounting for 1.6 percent, have obtained a second-child certificate, as opposed to the national average of 8.3 percent.

Interest has also been low in Jilin and Liaoning. "Since March 2014, only 70 qualified couples, about one-tenth of the total in our community, have submitted applications," said Zhao Xin, an official in Yizhongmingcheng, a residential community in Changchun, the capital of Jilin. "I know that not everyone who gets the certificate really wants to have another kid," he said, with reference to couples who obtain permission simply to ensure they will be allowed to have another child at an unspecified time in the future.

Fu Cheng, a researcher at the Jilin Academy of Social Sciences, said a wide range of factors influence couples thinking of having a second child. "More young people nowadays prefer small families. Factors such as finances, housing, education and age are also involved in making these plans. Most young couples want to give their children favorable conditions to grow up in, which involves high financial outlay. Many abandon the idea once they understand the difficulties," he said.

Liu Chang, 31, has just returned to work as a journalist at a newspaper in Harbin after maternity leave. She definitely doesn't want another child. "Absolutely not. My husband and I made this decision after much consideration, including finances, energy, emotion and self-development," she said. "In the past half-year, we found it much more difficult to raise a kid than we ever expected."

Liu's husband is a civil servant, and their combined monthly income is about 7,000 yuan, a reasonable sum in the city, but the birth of their daughter brought severe financial pressure. "We spent about 30,000 yuan alone on obstetric examinations during pregnancy and the natural birth of my daughter," Liu said. "That's about average in this city, but I know some families who paid several times more than that."

Furthermore, as an only child herself, the 30-year-old isn't certain she would be able to deal with the relationship between two children. "Recently, I have read several reports about how an older child refused to accept the truth that they would soon have a younger brother or sister," Liu said. "It really scared me when I learned that some kids had threatened to end their own lives if their parents decided to have a second child."

Today's Top News

12 firefighters among 44 killed in explosions

Chinese yuan extends fall Thursday

Tibetan drivers to finally see the end of 'death road'

China becomes world's largest robots market for second consecutive year

Yuan may stumble, but will not fall

Third Greek bailout deal submitted

to parliament

Pearson to sell 50% stake in Economist Group

Heatwave in Egypt kills at least 61

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|