Tears for the 'river pig'

Updated: 2011-10-27 10:49

By Wang Ru (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

|

A volunteer is distraught after seeing the Yangtze River finless porpoise rescued in Shishou, Hubei province, in May. Gao Baoyan / For China Daily |

|

|

Volunteers from Hohai University interview people living near the Yangtze River in Nanjing, Jiangsu province. Chen Chenghao / For China Daily |

Increasing pollution of the Yangtze River and the threat this poses to the finless porpoise is also a warning for a third of the nation's population that depends on these waters. Wang Ru reports.

Growing up in Huanggang, a city by the Yangtze River in Central China's Hubei province, He Dan had heard from elderly fishermen about a rare fish, dubbed the "river pig" by locals.

|

The fishermen described them as shy animals that often chased their boats, making a whistling sound. However, the term "river pig" was not really appropriate for the clever animal, that fishermen recall leaping out of the water in pairs or as a group.

He says she never spotted a "river pig" in her childhood, but did witness the increasing dredging of the river to feed the construction sites on its banks, and the resulting muddying of its waters.

He, a junior student of Chinese literature at Central South University in Hunan province, recalls how shocked she was to see a photograph that stirred much online discussion. It was of a rescued dolphin-like animal seemingly shedding tears. She learnt it was the "river pig" - the Yangtze finless porpoise - of her childhood.

"I didn't know dolphins could really cry until I joined the volunteer program funded by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) to protect the lovely but highly-endangered animal, but I now believe they do," He says.

Even as World Freshwater Dolphin Day was marked on Oct 24, the finless porpoise in the Yangtze River is likely to meet the same fate as the baiji, the Yangtze River dolphin known as "the Yangtze goddess", and declared "functionally extinct" in 2006.

According to WWF, after years of efforts by scientists and environment protection organizations, China's Ministry of Agriculture upgraded the conservation level of the finless porpoise from grade 2 to grade 1 in June. The move is awaiting final approval from the State Council.

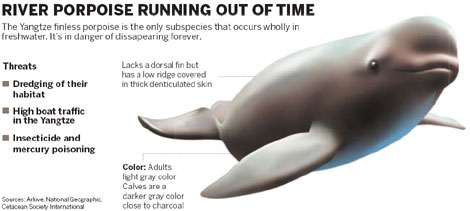

Scientists estimate that the finless porpoise, a freshwater dolphin which has lived in the Yangtze River and adjacent lakes for over 20 millions years, will become extinct within 15 years.

According to surveys done by the Hydrobiology Institute of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the population of the Yangtze finless porpoise was about 2,700 in 1991.

By 2006, however, the numbers had dropped to between 1,200 and 1,400, with between 700 and 900 in the Yangtze River and 500 in Poyang and Dongting lakes.

Now, scientists estimate the number of Yangtze finless porpoises is around 1,000 (there are more giant pandas), and the number is decreasing at the rate of 5 percent every year.

|

The picture of the "crying finless porpoise" was taken in May, when a severe drought hit Central China and lowered water levels in the Swan Island National Nature Reserve in Shishou, Hubei province, which is inhabited by some 30 finless porpoises. The river section favored by the dolphins has shrunk to a 10-20 km area, commented Wang Ding, a dolphin expert at the Hydrobiology Institute, in an earlier report.

The porpoises stay in shallow waters close to the bank - waters with a soft or sandy riverbed - eating fish and shrimp. A porpoise has a lifespan of about 20 years and can grow to anywhere between 1.2 and 1.9 meters long.

"If their activity area is reduced, they might become stranded on the bank and will die if they cannot swim back," he says.

Besides the extreme weather, human activities are a crucial reason for the deterioration of the environment.

"Human activities continue to severely threaten the finless porpoise. We have not learnt the lesson from the extinction of the baiji," says Wang Kexiong, another expert from the Institute of Hydrobiology, who conducted a three-day survey of Dongting Lake in Hunan province.

According to Wang, dredging, overfishing, heavy traffic and pollution are the major factors threatening the animal.

Dredging makes the waters of the lake muddier, so the finless porpoises cannot see as far as they once could and have to rely on their highly developed sonar systems to avoid obstacles and look for food.

Large ships enter and leave the lake at the rate of two a minute, and this means the porpoises have difficulty locating their food, and also cannot swim freely from one bank to the other.

In the research conducted in January, Wang found that dredging had cut off the only channel through which the finless porpoises could travel between the lake and the river, and this could have disrupted possible genetic exchanges among different groups of the species.

"Protecting the finless porpoise is about much more than maintaining wildlife diversity. If they die, it is a warning that the Yangtze River is not suitable for humans as well," Wang says.

Since June, WWF has recruited 15 volunteer teams, comprising college students involved in environment protection, experts and concerned citizens, to help protect the finless porpoise.

"Chinese people are familiar with the sad story of baiji, but few realize the finless porpoise is now on the brink of extinction. We hope the volunteer program can raise awareness about this lovely animal and the environmental changes in the Yangtze River," says Zeng Ming, a WWF officer in charge of the program, titled "Saving the Smile of the Finless Porpoise".

The teams have traveled to different sections of the central and lower reaches of the Yangtze River and adjacent lakes to research, survey and record the stories of the finless porpoise.

Li Xiuyuan, a volunteer from Hohai University in Nanjing, Jiangsu province, along with 18 other student volunteers, walked through these sections of the Yangtze for two days, interviewing people and distributing and collecting questionnaires.

It was reported that at the beginning of the year, many people in Nanjing saw finless porpoises under Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge.

"Some elderly citizens said they could see the porpoises jumping out of water in the 1970s and 80s, but they are rarely seen now," says Li, who majored in hydrology and water-resource management.

"The worsening water quality of the Yangtze River impacts the survival of the porpoises. If they become extinct, it will definitely be bad news for a third of China's population, who rely on the Yangtze River."

He Dan, who joined the Central South University team to travel to two towns and villages near Dongting Lake and investigate, says: "Some fishermen still use illegal fishing, such as electrofishing and gillnetting, which could be fatal to the porpoises," He says. "To avoid being fined, they often go fishing at night."

She is afraid she may never see a wild porpoise.

"I was moved by the picture of the smiling face of the lovely animal which has disappeared in my hometown. If they eventually disappear due to human activities, future generations will never forgive us," she says.