Trusting in wisdom of the crowds

Updated: 2015-07-17 09:05

By Cecily Liu(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

Chinese companies give own spin to West's platform business model for selling goods and services

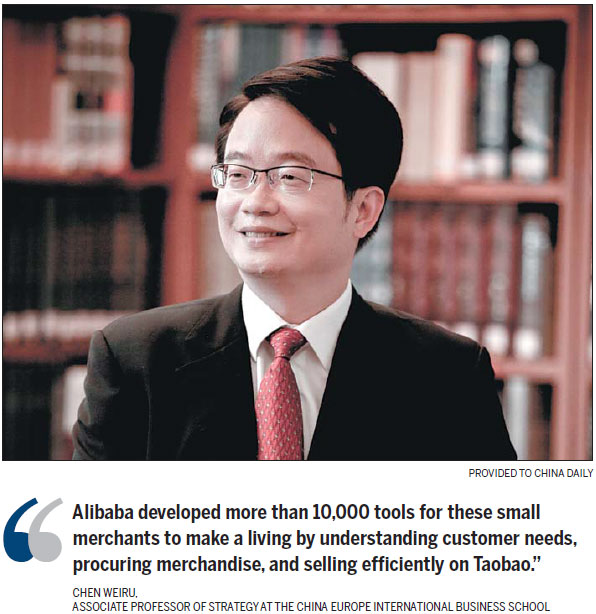

Chinese companies such as online shopping giant Taobao and smartphone maker Xiaomi are booming after revolutionizing a business model pioneered by Western Internet giants such as Facebook and Amazon, says business strategy expert Chen Weiru.

These Chinese companies have adapted the user-contribution or "platform" business model, developing it far beyond its original scope, says Chen.

In doing so, they are using it to beat big Western firms at their own game in the Chinese market.

The platform strategy first emerged in the West about two decades ago, as the Internet started to grow rapidly, says Chen, who became one of the first academics to study the system. He is an associate professor of strategy at the China Europe International Business School in Shanghai.

The original model was simple. Rather than selling a product, businesses would profit by creating a marketplace where buyers and sellers interact.

Chinese companies in recent years have taken this one step further by establishing institutional trust, Chen says. That has enabled the model to flourish in China's relatively primitive markets, creating huge profits because of the country's large population, he says.

One key reason that Chinese firms were compelled to establish institutional trust is that they realized China lacked reliable institutions to provide customers with standardized services, known as an institutional void.

In a developed market, if a company wants to find a good employee, or to commission a quality research report, there are reliable institutions that can provide such services. There also are recognized and respected rating systems that allow the company to judge the quality of the product or service.

But in a market such as China, where no such established institutions existed, there was a market for platforms to emerge to provide those functions. Taobao, which has features similar to Amazon and eBay, helps vet the quality of suppliers and works to ensure delivery is convenient for customers. Taobao is owned by Alibaba Group, which has become the world's biggest e-commerce company.

Chen bases his conclusions on a study of the platform business model based on 40 Chinese companies and 20 global entities. In 2013, Chen published a book based on that study, Platform Strategy - Business Model in Revolution, which became an award-winner that has sold 150,000 copies.

Chen notes that platform businesses also are rapidly taking hold in China's financial sector. China's state-run banks, which prefer to loan money to big, state companies, are less adept at loaning money to small and medium-sized enterprises than banks in mature markets.

As a result, peer-to-peer lending has grown rapidly in China. In P2P lending, companies borrow directly from individuals who have excess savings. This is facilitated by P2P companies.

While P2P lending is an idea that originated in the United Kingdom some 10 years ago, there still are only a few dozen P2P lending firms in the UK market. In China, there are about 2,000 P2P firms of various sizes.

"These P2P lending firms in China greatly increase liquidity for SMEs that otherwise can only go to the shadow banking sector to borrow money at very high cost. Meanwhile, P2P has allowed savers to increase returns on their savings. The growth of sectors like P2P lending in China is really driven by user demand," Chen says.

Another area where Chinese firms have made good use of a platform approach is in the taxi- hailing app industry, where Didi Dache and Kuaidi Dache revolutionized the local taxi market. The two companies merged this year to form Didi Kuaidi.

Prior to the emergence of such apps, taxi drivers had to work long hours to make enough money given the fixed fares and large fees they are charged by taxi companies. With taxi-hailing apps, the owner-drivers can efficiently find customers and earn more, giving them much more motivation to work harder to reap the benefits of their work, Chen says.

Such a platform would not work in markets such as Singapore, Hong Kong or Taiwan, he says, because the taxi-hailing systems developed by the leading taxi companies are already organized and efficient, meaning customers can easily call for taxis that belong to the largest companies.

In Singapore, for example, there are at least two incumbent taxi-hailing companies that have good mobile technology and a large fleet of taxis, meaning there is little room in the marketplace for new services.

While Didi Kuaidi's main rival, US-based Uber, moved faster on crowd-sourced P2P rides provided by drivers who don't operate taxis, the Chinese company has launched a P2P service that also has grown quickly. Didi Kuaidi also is hoping to do one better by making its app the answer to all commuters' transportation needs.

China's large population is another important condition that has allowed companies to benefit from a platform strategy. This is because the users of the platforms often are also its key contributors.

Chinese restaurant review site Dianping, for example, has gained credibility with customers because it has lots of users, which helps to attract even more users. This would be less effective in a country with a smaller population.

Chen says one reason that the platform strategy often has emerged from Internet industries or Silicon Valley in the United States is because old institutions are not efficient or innovative. As the economy continues to develop, institutions within the old ecosystem can no longer support growth, creating new business opportunities.

PayPal's emergence resulted from a lack of trust on the part of users of Visa and MasterCard in the security of online transactions, and Uber sprang up due to inefficiency in traditional taxi hailing.

Chinese platform businesses initially began as imitators of such ideas, but once they succeeded in the Chinese market, their scale exploded and they adapted their business plans to that market.

Alibaba, originally inspired by Western firms like Amazon and eBay, grew incredibly fast, achieving the largest initial public offering in the world last year.

"Unlike eBay, where most sellers are amateurs, most Taobao sellers are professional small merchants or individuals. Alibaba developed more than 10,000 tools for these small merchants to make a living by understanding customer needs, procuring merchandise, and selling efficiently on Taobao," Chen says.

"A company like eBay was familiar with markets where credit cards are widely used and accepted, but its business model could not work in China 10 years ago because, back then, Chinese people did not believe in online transactions. Alibaba created Alipay to protect online transactions and won the acceptance of buyers and sellers," he says.

Building on this expertise, last year Alibaba Group's finance arm launched a credit rating system called Ant Financial, which collects user data to establish a customer's credit rating.

"The Chinese market is unique in the sense that many consumers do not have a trustworthy credit rating, as many of them do not use credit cards. To establish a user's trustworthiness, Ant Financial collects behavioral data such as whether someone has ever been rude, canceled a taxi reservation without legitimate reasons, or not paid for a bus ticket.

"This is a great example of innovation specific to the Chinese market, a completely new way to think about credit history, because people's day-to-day behavior is reflective of their credit worthiness," Chen says.

In certain sectors where multinationals already dominate the market, some Chinese companies have broken into the market by building a two-sided platform business model. One example is the Chinese smartphone manufacturer Xiaomi, Chen says.

As a latecomer to the smartphone market, Xiaomi introduced cellphones with top specifications priced much lower than its competitors.

The company cut costs through selling its products largely online, taking many of its phone features from user input, and aiming for its primary profit center to come from software and services, not its handsets. It is exploring the revenue model of charging for Xiaomi apps on Xiaomi phones to control smart or connected homes. The apps would help them control their TVs, kitchen cookware, lighting systems and security, Chen says.

Xiaomi has moved its two-sided market strategy from hardware to services. In a recent promotional event, it was selling an interior decorating service for homes for 699 yuan ($112; 101 euros) per square meter, guaranteeing a fixed price and a completion period of 20 days, compared with competitors who may charge more than 1,000 yuan, with completion in 60 days.

The interior decoration service became popular in China, especially among young professionals who are first-time homebuyers and have little time to personalize their homes themselves.

Xiaomi has also invested in many home services companies, so that their strategic interests and future growth will be aligned with Xiaomi's.

"Xiaomi's profits are currently low. It is most likely Xiaomi's strategy to realize the majority of its profit from the platform it creates. To do so, it will need to build a platform that will be efficient for others to profit from before it sees any profits itself. But in the end, the platform's profit may be the largest," Chen says.

Although Xiaomi has not yet succeeded in achieving this home services platform, it may become as competitive as Apple or Samsung in the smartphone market if it does accomplish this.

Chen says he believes more companies like Xiaomi will emerge to take advantage of a platform strategy and find their own competitive edge in their respective markets against multinational incumbents.

"The inclusiveness inherent in the Chinese culture, as well as the fierce competition in the Chinese market, are all great elements that contribute to China's ability to develop platform businesses in the future and create game-changing business models," he says.

cecily.liu@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 07/17/2015 page21)

Today's Top News

China, World Bank pledge $50m for poor

Industries should be on digital Silk Road to expand market

'Occupy Central' leaders to stand trial

Europe moves to restore funding to Greece after bailout vote

MH17 final report to be published in October

ECB raises Greek bank funding as Europe backs new loan

Greek parliament approves debt deal and reforms

British boy with eczema wins support from Chinese Internet users

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|