A culinary incursion in Canada

Updated: 2016-11-04 07:25

By Hatty Liu(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||

Authentic Chinese flavors find a vibrant home in Vancouver on the Pacific Coast

As China's economy grows and Chinese dishes such as steamed buns and pancakes begin to appear in the bistros of US cities, a recent headline in The Atlantic was confident enough to predict, The Future is Expensive Chinese Food.

If that's true, the future arrived 30 years ago in Vancouver, a Canadian city on the Pacific Coast, and it has been changing so fast that few can keep up.

"Excluding wine, Chinese food is some of the most expensive food in Vancouver," says Lee Man, food writer and judge of Vancouver's Chinese Restaurant Awards.

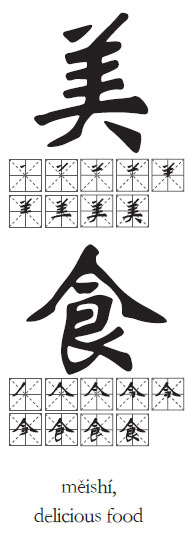

"It's a really unique city in that way. The word that really describes Vancouver's Chinese dining scene is ‘deep'; you can find any regional cuisine (地方菜 dìfāng cài), and different price ranges at Chinese restaurants - not just in Chinatown

(中国城 zhōngguó chéng) but all over the city," he says.

Chinese immigration to the Vancouver region, Canada's Pacific gateway, began with gold miners from San Francisco and picked up pace when thousands of workers were brought from impoverished regions of southeastern China to help build the Canadian Pacific Railroad.

When the work was finished and locals were suddenly no longer interested in hiring Chinese - or preferred they leave town altogether - the Chinese headed north and east and fanned out across cities and small communities across the country. Those who stayed banded together in some of Canada's first Chinatowns.

Faced with nativist laws that barred them from most sectors of business, restaurants became one of the few economic prospects open to these early migrants.

The foods they created reflected these harsh conditions and experiences of marginality. In Lily Cho's Eating Chinese, the two dishes emblematic of early and "inauthentic" Chinese dishes, goo lo yok (sweet-and-sour pork, a homophone of "white man's meat") and chop suey, were said to have been invented in the railroad camps and defined by the limitations of available ingredients and willing palates.

The vinegar (醋 cù) and bone (骨头 gǔtou) were left out of traditional Cantonese sweet-and-sour pork in favor of batter-coated sweetness, while the name chop suey literally referred to mixing together whatever ingredients (原料 yuánliào) one could find in the kitchen.

Over time, these dishes acquired a life of their own. They influenced the flavors of imported or invented dishes in migrant restaurants. They have also become a kind of comfort food, the Friday night take-out ritual.

Chinese restaurants became watering holes for the larger community, places where migrant and Canadian experiences intersect during pub-crawl nights and hockey games.

These stories are familiar ones, repeated in cities and towns across Canada as well as the United States. Late 20th-century Vancouver, however, saw a pattern in immigration that was decidedly unique.

Vancouver was their major destination because of its weather, relative proximity to Asia and Canadian immigration policies that rewarded those with high education and plenty of money to start businesses.

An estimated 167,000 Hong Kong immigrants settled in Canada between 1988 and 1991. Around 30,000 immigrants were said to have settled each year in the decade until the handover. Compared with the pioneers of the early century, these migrants were backed by sheer numbers and wealth, as well as business connections and better communication with their homeland - all the necessary ingredients for a food revolution.

Main course

With a culture that places food at the center of social and business interaction, it probably surprises no one that the English word "restaurant" could be translated from several different Chinese words, each with a different connotation for their price range, amenities, and social function.

The translation of one phrase connotes a mom-and-pop establishment, probably rather small, serving ordinary meals mostly for those who don't want to cook at home or for simple gatherings between friends.

On the other hand, another phrases refers to a type of restaurant whose main draw tends to be for "conspicuous consumption". That is, they are restaurants with multiple floors, teams of hosts and hostesses, glittery decor and, most important, private banquet rooms. They are places where you treat your business clients and friends, with emphasis on making the experience a real treat.

New mainland restaurants that have opened up in Vancouver in the past two to three years are often in line with the concept of the 酒楼(jiúlóu), or as food critics would call it, "fine dining".

As China's economy has grown, creating not only an expanding middle class but also millionaires, Vancouver has once again become a favorite destination for the transnational elite. Clean air, natural scenery, safe food and good education are the main selling points of the region.

On arrival, they start businesses, invest in local enterprises or homes, take vacations (while doing business back in China) and start influencing dining culture in their own way.

At establishments like Vancouver's Peninsula Restaurant (established in 2013) and Fortune Terrace (2016), banquet halls occupy one-third to half of the available seating in the restaurant. And there are no kitschy dragon motifs or fortune cookies in sight.

Instead, the decor consists of familiar mainland features like chandeliers and shiny drapes, though with more wood paneling.

On a regular evening, you might find a local Chinese-run company hosting a staff banquet or courting new business partners in the private rooms, or a table of Chinese businessmen toasting another day on the golf course.

Prices reflect the new clientele. At Richmond Sea Harbour Restaurant, located inside Richmond's River Rock Casino, appetizers cost around $18 on average.

At Chang'an, which is not a seafood restaurant and might be expected to save on the cost of ingredients, a conservative estimate, according to Zomato.com, for average price per person is around $50, roughly on a par with some fine French and Japanese restaurants in the city.

A "fine dining" category has been included in lists of local restaurant awards - for example the one by Vancouver Magazine, since at least 2007.

Traditional roots

It's important to note, however, that these glitzy newcomers are not isolated from the dining trends of the Hong Kong years. In 2014, for instance, a mainland investor who also owned a golf course bought Richmond's Sun Sui Wah Seafood Restaurant, one of the old-school Cantonese establishments from the early '90s, from the Cantonese family that owned it.

In addition to its regular services - the current manager is adamant that the menu has not been changed - the restaurant is now offered as a package deal with the golf course, so that tour groups and other players can patronize both establishments on the same itinerary.

Along with a bigger consumer market come higher standards for authenticity, quality and innovation in the product.

Chang'an's Shaanxi-style cuisine, and new restaurants specializing in Sichuan and Hunan fare are cooking at a level of specialization unseen in any other North American city.

Lee Man, the food writer, refers to this phenomenon as "confidence". "This new batch of restaurants, this new wave of immigrants from the mainland, have a swagger, have ambition," he says.

"This new wave of energy from the Chinese mainland is about celebration and bigness: big rooms, crazy prices, beautifully renovated, beautiful clay pots imported from China. They are who they are, and they don't have to dumb it down to please anybody."

Reverberation

The growing Vancouver market for authenticity and "newness" in Chinese food is starting to reverberate back in China, with the mainland corporations and even the government taking note of opportunities for investment and exchange.

According to Hellen Ran,

Liuyishou's North American general manager, it simply made business sense in the past to start with Vancouver.

But with a cuisine that has always adapted to circumstance, positive or negative, through the past 100 years, it's hard for anyone to tell what new tricks it has up its sleeve.

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com

The World of Chinese

(China Daily European Weekly 11/04/2016 page23)

Today's Top News

High Court rules against government over Brexit

Court to instruct how to trigger formal EU exit

Premier emphasizes fight against terror

Italian authorities vow to rebuild earthquake-hit areas

Li arrives in Kyrgyzstan for visit, SCO meeting

Xi affirms one-China policy

France to begin moving migrant minors from Calais

Red Arrows flying high for first China display

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|