Food from the Forbidden City

Updated: 2016-01-15 07:44

By Pauline D. Loh(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

"For the people, food is heaven," according to Sima Qian, a historian in the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24). Today, these words still ring true. The Chinese respect and passion for food is firmly entrenched in the cultural landscape, creating a culinary scene that reflects the vast geographical footprint of the world's most populous country. Pauline D. Loh offers a view from the table.

In a country where good food is a prime motivator cutting through every social strata, the capital is where the Chinese Paradox reigns.

When the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) ruled, masters of Lu (now modern-day Shandong province) cuisine loaded the imperial tables with exotic delicacies such as sea cucumber braised in onion oil and top stock, abalone, squid roe consomme, and Peking duck.

Even in Beijing today, the residual frugality is still reflected in the way diners are less willing to spend compared with, for instance, those in Shanghai or Hong Kong.

Perhaps the flavors of China had congregated in the palace together with the best ingredients and chefs, but northerners still preferred their food hale, hearty, strongly flavored and, most of all, filling.

The parochial palate again reflected the city's past when caravans from the Silk Road dispersed at its very gates. Thus, cumin, star anise and Sichuan peppercorn were introduced and widely used to spice up daily meals.

Noodles were staples, as were steamed breads. They still are. Stuffed with meat, they are called baozi, or are known as mantou without the filling.

Beijingers ate a lot of tripe and intestines. The off-cuts of meat were turned into the city's signature dishes like chaogan (fried liver) or baodu (beef tripe). Chaogan is a starchy brown stew with bits of liver, lung, tripe and intestines braised in an aromatic gravy. A bowl of this is usually accompanied by a few sticks of fried dough, shaobing, or a couple of mantou for a substantial meal.

The true test for the determined gourmet in Beijing is a bowl of douzhi, fermented bean juice, a tart and pungent concoction reminiscent of a ripe gutter.

This is a byproduct of making beancurd, and native Beijingers swear by its health benefits. To the uninitiated, it's a little like drinking overnight liquid blue cheese.

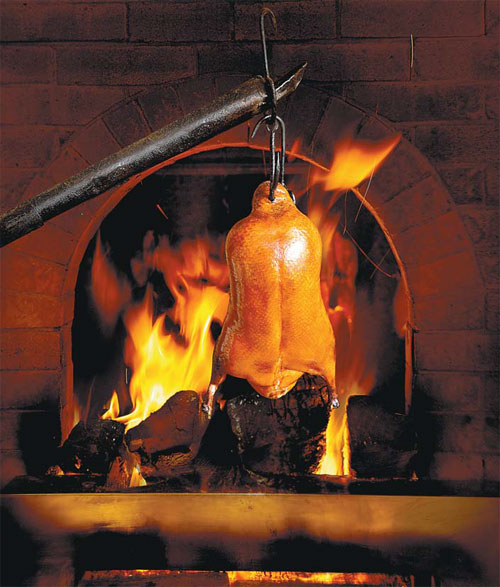

There is, of course, the famous bird named after the city - Peking duck, which is barbecued over an open fire of fruit wood, usually cut from the native Chinese jujube growing around Beijing.

The ducks are force-fed so they have a thick layer of fat under the skin. This keeps the meat moist and flavorful.

It may be just a roast duck, but it is the almost ritualistic way it is served that makes it Peking duck. The craftsmanship goes beyond the kitchen and is extended tableside when chef and duck go before the diners. The knife flies as the chef shaves first the duck skin and then the meat into exactly numbered slivers, enough to serve a full meal for four or five.

The slices are delicately smeared with a sweet bean paste, rested on a bed of shredded cucumber, spring onions or radishes, and wrapped in a bite-sized, wafer-thin crepe.

Rolled into little envelopes, these duck pancakes are a taste and tactile experience that most characterizes the sophisticated palate and pragmatism of the city.

Beijingers also like to dip the fatty duck skin in sugar to emphasize the crunch.

The bird carcass goes into a pot with white cabbage, and a rich duck broth is served. Sometimes, any extra meat is stripped from the bones, shredded and stir-fried with garlic chives or asparagus. Nothing is wasted.

Next week: Heart-touching Southern food

Where to eat Peking duck in Beijing

Quanjude

This is the original restaurant that has been serving traditional Peking duck since 1864. It is now state-owned and is probably the capital's most iconic duck restaurant. During the 2008 Olympics, it gave international athletes staying at the Games Village a taste of Beijing. At the same time, it also switched from using traditional wood ovens to gas. It has many branches in Beijing, but the most famous is still at Qianmen in the heart of the city.

Da Dong

Named after the chef, this is where you go for a modern take on Peking duck, and a taste of Lu cuisine, the de facto representative of imperial cooking. Da Dong's ducks are leaner, and more suited to suits and skirts with an eye on the waistlines. The birds are still cooked over fruit wood. The chef's signature dish is sea cucumber braised in leek-infused oil. Prices are steep, but you get to enjoy pretty platings that are often lyrical.

Shang Palace, Beijing Shangri-la Hotel

Very popular with the business set, this restaurant serves an efficient version of the old favorite. Ducks are a lot less fatty, and every slice is carefully cut to include meat and skin. The traditional garnishes are all present, even down to the tiny saucer of sugar. Besides, you can also order dim sum.

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese firms making inroads in UK

Value addition

IS claims Jakarta attack, targets Indonesia for 1st time

Chinese people most optimistic in global survey

COSCO offers 700m euros for Greece’s Piraeus Port

Istanbul bomber entered Turkey as refugee

Bird flu case confirmed in eastern Scotland

Cosco poised for Piraeus control

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|