Labor of war for Chinese

Updated: 2014-07-18 08:29

By Cecily Liu (China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

|

Former Chinese foreign minister Li Zhaoxing visits a cemetery of Chinese workers who served on the Western Front during World War I in Noyelles-sur-Mer of France on July 15. Li was in France to attend events to mark the 100th anniversary of WWI. Tuo Yannan / China Daily |

|

Entrance to the cemetery where Chinese workers are buried. Tuo Yannan / China Daily |

Renewed interest in Chinese workers' contributions during WWI helps shed new light.

Many people have forgotten, or are even unaware, that 140,000 Chinese workers served on the Western Front during World War I. These workers' contributions as manual labor during the war were significant, scholars say. Most of them were volunteers, farmers in search of better wages. One hundred thousand of them formed the Chinese Labour Corps under British forces, and 40,000 were employed by French factories and farms.

Chinese intellectuals then believed that the contributions of the Chinese workers would even give China an added advantage during negotiations at the Treaty of Versailles following the war, but their hopes turned out to be futile.

After the war, the contributions of the Chinese workers were largely forgotten by both Chinese and Europeans.

It is only in the past decade that academic interest in the subject began to grow. Amid the run-up to the war's centenary events, many believe that the focus will help shed new light on how China should view its relationship with Europe.

"This is about our history meeting your history. I think that's important because having a common history creates an opportunity for meeting and discussion," said Dominiek Dendooven, a senior curator at the In Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres, Belgium.

"Secondly, this is an important part of our history and your history. It is a major influx of Chinese immigrants that directly links China and Belgium, and is an important moment in our history," Dendooven said.

To remember this part of history, In Flanders Fields organized an exhibition in 2010 which showed visitors the story of the Chinese workers' arrival in Europe, their lives there and what happened to them after the war ended.

The exhibition, from April to August 2010, spanned 450 square meters and attracted 70,000 visitors.

Author Mark O'Neill has also written a book about the forgotten Chinese laborers of World War I, which was published by Penguin as part of its collection of new books on the war.

Similarly, independent film producer Helen Fitzwilliam made a short film and wrote an article on this issue, which was presented at London think tank Chatham House in June.

A new book on Chinese overseas labor and globalization in the early 20th century, written by historian Paul Bailey, will be published in November.

Dendooven said the revival of interest on Chinese workers' roles during World War I started around 2004 and 2005, and coincided with the re-emergence of China on the world stage.

Bailey said one reason for Western countries' increasing willingness to revisit this part of history is the tourism element associated with historical events.

For example, the French government is keen to promote towns like Montague, where many of the Chinese workers lived, and where they later came into contact with Chinese students studying in France at the time.

Bailey said that it is also in line with the Chinese government's intention to depict China as a responsible rising global power in recent years.

"It fits in with this wider agenda of promoting China's globalization and positive interaction with the world," Bailey said.

Life of Chinese workers

The Chinese workers were seen by many scholars as passive victims. They dug trenches, buried the dead, worked in munitions factories and cleaned up the shells, grenades and cartridges after the Nov 11, 1918 armistice.

They were treated badly by the French and British. They were segregated in camps under armed guards, and punishments inflicted on them included beatings, prison sentences for strikers and fines for insubordination.

One source showing this mistreatment is a diary kept by Father John Van Welleghen, a Belgian parish priest in Flanders. His diary entries showed the sympathetic attitude of the local people toward victims of the British army's harsh methods.

He wrote: "I passed by the camp and saw three of them tied with arms outstretched on the wire of the perimeter fence. One of them also had his legs tied. It can't have been pleasant in this wintery weather. Today it has been freezing hard."

O'Neill said he believes one reason the Chinese were mistreated is because the British and French armies suffered enormous casualties during the war and their spirits were low.

"They just wanted to get the war finished. They were not in the mood to welcome or understand new people," O'Neill said.

The second reason for the mistreatment was because they were under the colonial mindset that white people were the superior race, he said. "That is not correct, but it was the common attitude at the time," O'Neill said.

The British and French also did not understand the Chinese as they had no prior knowledge of these workers' culture and country. They believed that treating them strictly would make them easier to control, O'Neill said.

Like Van Welleghen, O'Neill's grandfather Frederick O'Neill came in contact with the Chinese workers in his role as a minister of the church. He spent two years in France serving the Chinese Labour Corps and wrote a diary about his experiences.

Frederick O'Neill lived among the Chinese workers, providing them with spiritual support. He would help them write letters to send to their relatives in China, and help them organize recreational activities like sports events and singing and dance performances, to help the workers take their minds off the war.

O'Neill said his grandfather's attitude toward Chinese workers was very different from most others.

"He believed that everyone is the same, as everyone is a child of God. He saw all of them as individuals, someone with soul, spirit and family," he said.

Frederick O'Neill's work inspired Mark O'Neill's interest in this period of history, which led to the publication of his book. In the book, O'Neill also devotes considerable attention to the fate of the Chinese workers after the war.

O'Neill gathered most of this information from Zhang Yan, a researcher in the history department of the University of Shandong, who interviewed the descendants of 65 returnees, largely in the Zhoucun district of Zibo in Shandong province.

"The workers came back from the war, some of them had money which they earned during the war, but many were traumatized by what they had seen-the shelling, killing, mines and horrific injury of people. They didn't want to speak about it," O'Neill said.

Returning to China had been almost a cultural shock for them as rural Shandong was very different from Western countries. Many Chinese workers became literate during their time abroad, but these skills were no longer useful after they returned. Many Chinese workers had earned money during the war, but this money was likely to be divided up between relatives.

Some of the workers had married French women and brought them back to Shandong, but the relationships did not work out because the French wives did not speak Mandarin and could not gain acceptance from the local community. Many of them went back to France.

Others had married French women and stayed in France. Very often they had happy marriages and had children, O'Neill said.

Implication for history

The Chinese workers may have felt forsaken but so did Chinese intellectuals. Many scholars say China's role prevented a German victory, but politically it seemed that China had gained nothing from the war.

After the armistice, the 1919 Treaty of Versailles saw Germany's concession ports in China handed to Japan, despite China's objections.

News of the fate of Shandong triggered an uproar in Paris, as Chinese students and activists surrounded the Hotel Lutetia where Chinese diplomats were staying.

At home, unhappiness over the treaty led to the May 4 protest movement, which was an anti-imperialist, cultural and political movement growing out of student demonstrations in Beijing on May 4, 1919. It marked the beginning of the New Democratic Revolution, and contributed to the rise of the Communist Party of China.

Another important link between the Chinese workers and modern China is their interaction with many Chinese students in France in the 1920s, including Chinese leaders Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping.

Dendooven said it is still unclear as to what influence the Chinese workers had on Zhou and Deng, and this is a question that historians and academics are still striving to answer.

"Zhou and Deng would have read about the working and living circumstances of these Chinese workers, so they must have influenced them indirectly," Dendooven.

Looking into the future, Dendooven said he believes the involvement of Chinese workers in World War I will gain increasing attention as more books, television programs and exhibitions focus on this topic.

At the same time, the discovery of important written and oral evidence will help the body of scholarly work on this topic grow.

"So (the interest) is now trickling down to the broader public level, but it could still take us many years," Dendooven said.

cecily.liu@chinadaily.com.cn

|

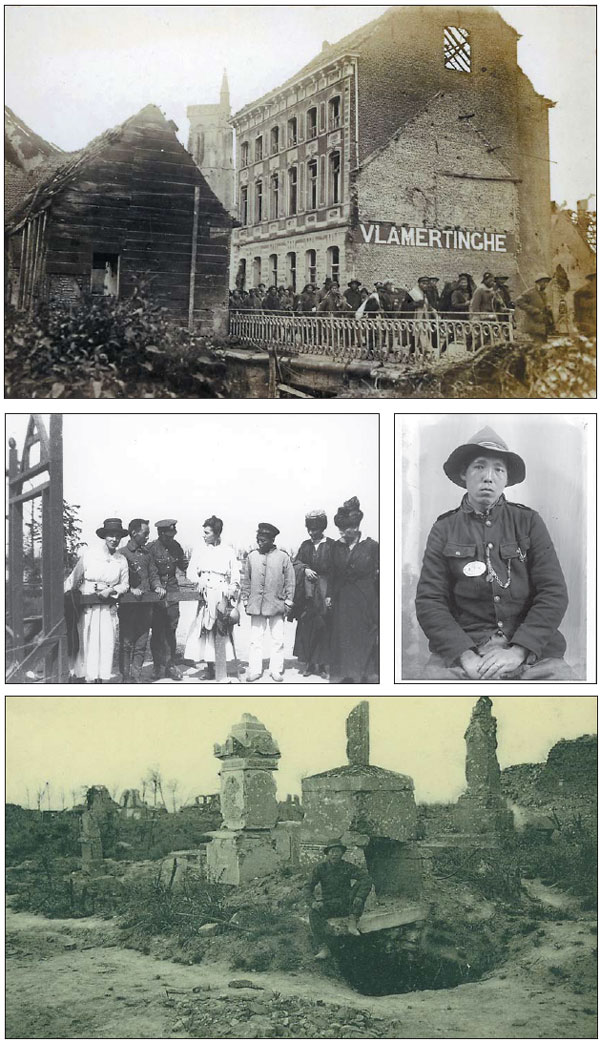

Top: A unit of the Chinese Labour Corps passing through the ruined village of Vlamertinghe near Ypres, Belgium. Center left: Visitors to the former battlefields meeting Chinese laborers and their British officer in Flanders, Belgium in 1919. Center right: Wang Jinyong, a Chinese laborer. Above: A Chinese laborer amid the destroyed graves in the churchyard of the village of Dikkebus near Ypres of Belgium. Photos Provided by in Flanders Fields Museum to China Daily |

(China Daily European Weekly 07/18/2014 page24)

Today's Top News

Burning wreckage, bodies scattered after jet downed

US widens sanctions on Russia over Ukraine

Hamas agrees on 5-hr ceasefire

Chinese killed in Moscow metro derailment

Obama vows info co-op to Merkel

Filipinos flee as typhoon hits coast

China ends drilling operations in South China Sea

Economic ties with Latin America grow

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|