Mid-priced brands ready for the boom

Updated: 2014-03-07 09:43

By Todd Balazovic (China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

As Chinese winemakers corner more of the domestic market, foreign brands are still fine-tuning their marketing strategies

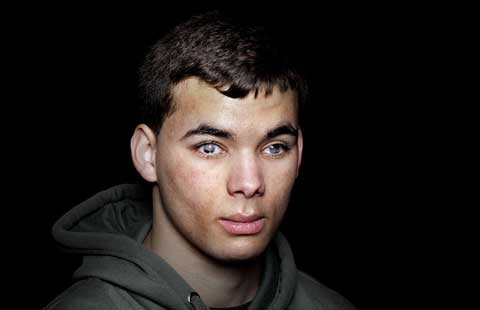

Taking a measured sip of a vintage Bordeaux, Libin Gao swirls the dark liquid in his mouth, pausing to reflect before scratching down a few notes on the form beside him.

It's a Saturday afternoon in Beijing and class is in session. For Gao and the 12 other students occupying Dragon-Phoenix Wine Consulting's packed 8th floor classroom it's a chance to make Chinese wine history.

Gao, a member of the pilot program that teaches Level 3 Wine Spirit Education Trust Certification in Mandarin, will, on successful completion of the course, become one of the highest-ranked wine experts in China.

As regional manager for Joyvio, Lenovo's food and agriculture venture, Gao knows that getting an international certification would give him an upper hand in one of China's most lucrative industries.

"In the Chinese market right now, much of the focus is on the packaging of wine. I want to be a part of the movement that will shift the focus from packaging to what's actually in the bottle" Gao says, during a 5-minute breather from the 8-hour class.

For Gao, the course is a chance to gain a competitive edge. But for wine producers, changing the way Chinese perceive and consume wine is a necessity for an industry that is undergoing tumultuous change.

Huge appetite

In the past five years China has had a ravenous thirst for wine, fueled by middle-class consumers flexing their spending power and a shift in drinking habits from beer and baijiu (white spirits) to purportedly more healthy red wines.

Sales of imported wine grew from $1.29 billion in 2008 to $5.49 billion last year, enjoying annual growth rates as high as 50 percent, according to a report published by Vinexpo, a leading French wine fair operator.

In 2013, China was the largest consumer of red wines globally, overtaking France and Italy where the quantity imbibed has been falling, and accounted for consumption of more than 1.86 billion bottles, the report said.

However, during the past five years, wine sales have also polarized in China, with purchases of either high-end or low-price wines dominating sales figures, says Edward Ragg, co-founder of Dragon Phoenix Wine Consulting, a leading independent wine consulting company in China. "Traditionally, there hasn't been a real market for middle-priced wines," he says.

Ragg, who helped found Dragon Phoenix Wine Consulting in 2007, has been assisting foreign wine producers and educating consumers in China.

"China was, and still is for the most part, a market where sellers can name their price," he says.

"If you, as a wine importer, were more likely to sell a 100 yuan ($16; 12 euros) bottle for 200 yuan, and the buyer was more eager to buy the more expensive product, why wouldn't you?"

He says while the past five years have seen a boom in wine sales, growth is slowing as bulk purchases by state and corporate clients dry up, with producers emphasizing more high-quality, low-priced wines.

"There are a lot of people who got on the bandwagon selling wine during the early boom years and they're realizing that China is not the massive wine market in the way people think it is," Ragg says.

Recent austerity measures to curb gift-giving and spending at official banquets have shrunk large orders of fine wines, with sales growth slowing from 18 percent in 2012 to just over 5 percent in 2013.

With an overabundance of up-market wines and distributors eager to find buyers, sales of top-end wines in China have hit a plateau, with prices of some of the most expensive brands dropping, in some cases by more than 50 percent.

In 2013, the price of a 2008 Lafite wine tumbled 53.4 percent to 7,230 yuan ($1,180), and the price of a 2004 Lafite wine fell to 2,850 yuan from 4,900 yuan.

The shift has seen dozens of distributors, who once catered solely to the fine wine market, go bankrupt, with stocks of high-priced wines remaining buried in warehouses.

"The top end of the market has pretty much become flat," says Nikki Palun from De Bortoli Wines, Australia's fifth-largest exporter of wine.

"Most of the businesses that focused on the government and corporate channels have become bankrupt or are saddled with excess inventories."

She says as a result, many producers have had to promote sales of entry-level, lower-price wines.

"To stay afloat in the wine industry in China you have to target those people who are using their own money to buy wine. As a result the prices have dropped."

China's wine drinkers have traditionally stuck to domestic brands. More than 80 percent of the wines drunk in China are domestically produced, with imports hovering between 15 and 20 percent in the past five years.

The biggest advantage Chinese vineyards have is in understanding how to effectively establish operations and market to Chinese clients, says Judy Leissner, owner of Grace Vineyard, the only family-owned boutique winery in China.

"An obvious advantage that a domestic producer has is the understanding of the local market. This is something that foreign producers can expect to gain only over years," she says.

"Domestic producers also understand better how to operate in China, for example how to set up a winery, which department to deal with, how to deal with the growers and government, and what incentives are available."

Set up in 1997, Grace Vineyard has won several international awards and is one of a handful of Chinese vineyards pushing the envelope to get Chinese wineries global recognition.

Leissner says the relatively low number of Chinese wine producers catering to high domestic demand has given Chinese producers an edge when marketing Made in China wines.

"It's easier to market a Made in China wine because there is still far less competition. Bordeaux itself has over 10,000 wineries. China as a whole has fewer than 1,000. It's easier to stand out as a Chinese winery in China," she says.

Despite ample success in the past five years, she says Chinese wineries have also felt the pressure from government austerity measures. Last year marked the first time since 2003 operations did not turn over double-digit growth, Leissner says.

Shrinking demand for premium wines has created an opportunity for Chinese drinkers to get access to quality foreign wines at low prices. Competing with low-priced and often less-sophisticated Chinese wines is an environment where taste, rather than packaging, is the primary selling point.

"Traditionally, people in China have looked to wine to give a sense of status. It's all about projecting this image," says Jim Boyce, author of Beijing-based wine blog, the Grape Wall of China.

He says this has changed with government measures to deter lavish gifts.

"In the past decade, taste has been a minor reason for people buying wine in China.

"Now sellers have to find customers who actually want their wine because they like it. I think we're moving into an era where consumers have a lot more power.

"By bringing the consumer forward it's creating a healthier market. It's creating a market where people will buy wine based on taste and value rather than price, a famous name or because the buyer has a big budget to spend."

The gradual move away from premium wines with a well-established name has opened doors for smaller foreign wine producers willing to cater to changing Chinese tastes.

Despite sluggish sales for China's mid-level wines, Helene Le Ponty moved to Beijing from her small village in Bordeaux hoping to find a niche for her family's wines.

Opening Le Ponty Wine's first international office in Beijing in 2012, the fourth generation owner of the 105-year-old Fronsac-based chateau says she wanted to avoid traditional distribution channels to market directly to China's wine drinkers.

"When I first arrived here, everyone was telling me that there wouldn't be a market for my wine. They said you have to be either very cheap or very expensive," she says.

"I thought to myself there is an interest in mid-level wines, people are just over-pricing them."

With low-end wines starting at 100 yuan and higher-end going for up to 1,200 yuan, Le Ponty has so far found hungry demand for her wines. Last year, she sold roughly 24,000 bottles in China, 33 percent of the 72,000 bottles Le Ponty Chateau produces every year.

Pushing to make her product more identifiable to Chinese drinkers, the chateau has translated the names of their wines on offer in China, transforming French names like Grand Renouil, the name of the river near Le Ponty's vineyard, into Mandarin-friendly Ge Hua Lu, roughly translated as "a heavenly drink".

Le Ponty says for a small brand, targeting a specific city, rather than trying to go national immediately, has been the foundation of her success.

"The problem with China is that to be a national brand is almost impossible because of cost. Only a few brands can do it. To be a local brand, even in the city of Beijing with 20 million people, if you're a small winery you just cannot serve the city," she says.

"This is such a large country and you only need a small slice of people to care about your brand to make it viable."

New frontiers

While for smaller operations, starting local is crucial, established brands are looking beyond first-tier cities for growth.

Palun of De Bortoli Wines, which has been operating in China since 2006, says getting out of over-supplied and highly competitive cities like Beijing and Shanghai has been the company's key strategy to sustaining high growth.

"What's really exciting now are the second-tier cities. New wine consumers and new wine businesses are springing up all over the country," she says.

Though sales figures in major cities have started slowing, she says growth in second-and third-tier cities has continued to flourish.

With many international businesses also seeking expansion in second-tier cities, utilizing wine's role in business entertainment has proven successful for De Bortoli.

"The great thing about China in terms of future potential growth is that wine has become an essential part of business," Palun says.

"This is where we are very lucky. Chinese people love to do business therefore they will be drinking a lot of red wine."

But, like many in the industry, seeing the dip in sales for corporate occasions following the austerity measures, Palun says she feels the real growth lies in educating and establishing a knowledgeable consumer market.

"What I'd love to see is that the market moves away from being just a business-related activity to something where people actually enjoy the product, buy it in shops and take it home," she says.

For many wine producers, this means targeting China's young, more internationally savvy generation of wine drinkers.

Few have made better efforts to attract China's next generation of wine drinkers more than Claudia Masueger, founder of Beijing-based wine wholesaler CHEERS!.

Beginning with MG Wines distribution company in 2008, Masueger has grown her wine wholesale chain to include 15 locations in just over five years.

Talking above bass-heavy pop music on the second floor of her most recent location in Beijing's traditional Gulou neighborhood, the Swiss describes arriving in China just before the country's wine industry took off.

"The first thing I noticed when I arrived was that there was a huge interest from the younger generation," she says.

"The second is that all the wines in China were way overpriced."

While working as a distributor, she says many of her clients would mark up the price of her wines by as much as 100 or 200 yuan.

"That made me crazy. I thought 'this is unfair'," she says.

On the first floor of her shop, imported wines from top wine-producing countries sell for as low as 28 yuan, with only a few reaching beyond 100 yuan.

Focusing on selling in volume rather than high margins on individual bottles, Masueger is trying to change the way people look at wine, she says.

Receiving endorsement to begin WSET classes in mid-February, Masueger's next step is teaching the next generation of Chinese how to understand and appreciate wine, while enjoying themselves in the process.

"We want to take this stiff wine image away," she says.

"So often, drinking wine is seen as this rich, stuffy activity. I don't believe that has to be the case," she says.

"I think life is difficult enough, so let's make the best out of it. I think drinking a glass of wine is a good way to do that."

toddbalazovic@chinadaily.com.cn

|

Customers select imported wine at a shopping mall in Yiwu, Zhejiang province, in January. Lu Bin / for China Daily |

(China Daily European Weekly 03/07/2014 page16)

Today's Top News

The search for flight 370 goes on

Obama to meet Ukrainian PM

China to curtail death penalty

Tougher penalty for underage prostitutes

Dailai Lama 'sabotaged ties'

777 vanishes: Malaysia Airlines says so far no evidence of any wreckage

Malaysia plane crashed off coast of Vietnam

'I was supposed to be on that plane'

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|