In Japan, the sun also sets

Updated: 2013-02-01 09:13

By Giles Chance (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

Ructions in Tokyo could have implications on china, rest of the world

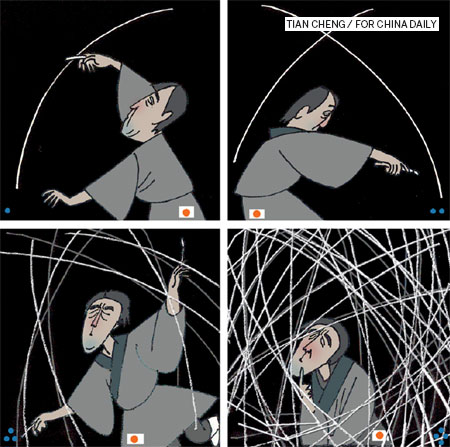

Shinzo Abe's election in December as prime minister of Japan could mark an important shift in Japan's policy. Since the country emerged from its diplomatic isolation in 1868 it has shown itself capable more than once of influencing global events and ideas to a much greater extent than its size and position would suggest, and not always in a beneficial way. Today two situations are developing that could again make Japan the center of a ring of economic and diplomatic disturbance whose ripples could spread around the world. One situation is the diplomatic impasse with China over the Diaoyu Islands, which shows the potential to boil over into armed conflict. The other is Abe's monetary reflation plan, which may cause a Japanese financial crisis because of Japan's extremely high levels of debt.

The remarkable rise of Japan's multinationals to world leadership in the 1980s showed the capacity of this relatively small country to have a global impact. When I was studying at business school in the US nearly 30 years ago we spent a lot of time studying the Japanese management system, because US business had been shocked by Japan's economic success. This system was based on a philosophy that the Japanese had learned from a US statistician and management guru, J. W. Deming. Deming, born in 1900, was an academic who believed that companies should focus on quality, organizational harmony and the long term. Ignored in his own country in the 1950s, he discovered a willing audience in a war-ravaged Japan, which found in his ideas about organizational design and management a way to re-establish Japan's national pride and global position.

By the 1970s Japanese products, particularly consumer electronics and cars, were penetrating Western markets. They were followed a decade later by Japanese capital searching for famous assets in the West, such as pictures by the Dutch master van Gogh and landmark buildings in London, Paris and New York. By force of its collective will and national pride, Japan came to assert a global influence far greater than the size of its population.

But Japan's return to the world scene as a dominant industrial force in the 1970s and 1980s was not accompanied by a modernization of the financial system or by an opening to foreign investment and ownership. The revaluation of the yen against other major currencies after the Plaza Accord in 1985 unbalanced Japan's economy and aggravated its financial bubble. After the crash in 1990 Japan again acted as a model to the West, but this time as an example of how not to deal with a stagnant economy and how not to escape a debt trap.

Even so, today, even after two decades of economic stagnation, Japan remains a vitally important economic and political force, not just in Northeast Asia but worldwide, by virtue of its close ties with the US and the size of its economy, still the world's third largest. No one can ignore Japan, particularly China, which finds itself in a quandary as to how to conduct its Japanese relations. On the one hand, economic relations between the two provide both with an essential source of growth and prosperity. On the other, Japan's refusal to recognize in full China's deep feelings about the Japanese wartime record continues to poison Sino-Japanese relations, making a settlement of the island dispute extremely difficult.

Against this background, there are two reasons why the succession of Abe as Japanese prime minister could have important global implications. The first is that a part of his election campaign was based on "standing up to China", an obvious vote-winner in a proud, but relatively small country positioned next to a fast-growing, much larger China, whose culture deeply influenced Japan's in previous millennia. Will Abe's election rhetoric be translated into a more aggressive posture toward China?

Clearly some agreement between Japan and China over the Diaoyu Islands is essential for both parties, and for the rest of East Asia, even if it is only an agreement to disagree. A neutral observer would think that the escalating dispute and the importance of China as a trade partner to Japan would demand that Abe place a China visit at the top of his diplomatic agenda. Instead his first post-election visit was to Vietnam, Thailand and Indonesia, three members of ASEAN, who could join with Japan to limit China's growing influence in East Asia.

It is difficult for China to see this as anything other than a diplomatic snub by Japan, and it will make a rapprochement more difficult. A Sino-Japanese armed conflict, which could spread, would obviously be a disaster for everyone concerned. Only a strong US effort may avert a steadily worsening situation. But the US is not in the mood for global power-broking, having its own financial problems to worry about. So an armed conflict is not impossible.

But Abe's desire to end Japanese price deflation raises an economic issue whose potentially negative consequences have equally great global significance. In the election campaign Abe called for this major change. Now he looks determined to carry it out. Indeed, he is supported by many economists, who have argued that Japanese growth can only resume in the presence of gently rising consumer prices that encourage Japanese households and Japanese companies to spend rather than save.

But if national debt is measured as a proportion of GDP, Japan's two decades of government spending and almost no economic growth have turned the government into a much larger borrower than the US government. The US can maintain its position as the world's largest debtor because the US Treasury manufactures the world currency, the dollar. For the moment at least, the world's major economies still find the dollar the most convenient currency for trading, borrowing and lending, and storing their national wealth. Even though investors and commentators worldwide are asking questions about the US' ability to manage its financial affairs, it is still relatively easy for the US Treasury to raise dollar debt.

Japan is able to borrow more than twice its economic output only because Japanese savers, both households and corporates, have been happy to acquire and hold Japanese securities backed by its government. Many observers have tried to explain continued lending by Japanese savers to Japan's government as a typical Japanese display of nationalism. But the more important factor in deciding to buy Japanese debt is the expectation by Japanese corporate and household savers of the positive real returns that are made possible by expectations of steadily falling Japanese consumer prices.

So what will Japanese savers do when Japanese price inflation starts to turn positive? In this environment, debt that is repaid in money starts to shed its real value. If interest rates remain near zero and as price inflation rises, appeals by the government to Japanese nationalism will not be enough. Medium and longer-term Japanese interest rates will rise as Japanese bond investors start to demand positive real rates of return. If, on the other hand, the Bank of Japan counters higher price inflation with higher interest rates, as it should, then the yields on short-term Japanese debt will also rise.

Japanese bond prices are likely to continue to fall, and so the huge bond portfolios of Japanese financial institutions that hold most of the country's debt will fall in value. As these core assets depreciate, many Japanese institutions, threatened by insolvency, could meet their losses by selling off their large holdings of liquid foreign investments, starting with the US Treasury market, where $1.1 trillion (819 billion euros), or nearly 10 percent of total US public debt, is held by Japan. A Japanese financial solvency crisis could cause US interest rates to rise and US bond prices to fall, at a time when American economic recovery is threatened by the so-called fiscal cliff, and Europe continues to struggle with its debt overhang and weak banks. Global mortgage rates would rise.

The Japanese government would probably step in to recapitalize its financial sector, using money printed by the Bank of Japan for the purpose. But the size and global reach of Japanese financial institutions could magnify the impact of the crisis into a major worldwide event reminiscent of the 2008 crash in the US. The implications of a big Japanese financial crisis for other Asian countries, including China, would be serious.

For years it is China that has been at the center of the forecasts of Western doomsayers. But China's predicted economic and social collapse has not happened. Instead, today it is Japan that looks far more likely to prompt a major crisis.

The author is a visiting professor at Guanghua School of Management, Peking University. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily. Contact the writer at gileschance@gsm.pku.edu.cn.

(China Daily 02/01/2013 page10)

Today's Top News

List of approved GM food clarified

ID checks for express deliveries in Guangdong

Govt to expand elderly care

University asks freshmen to sign suicide disclaimer

Tibet gears up for new climbing season

Media asked to promote Sino-Indian ties

Shots fired at Washington Navy Yard

Minimum growth rate set at 7%

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|