Finding the right balance

Updated: 2011-11-25 08:54

By Xiaohe Cheng (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

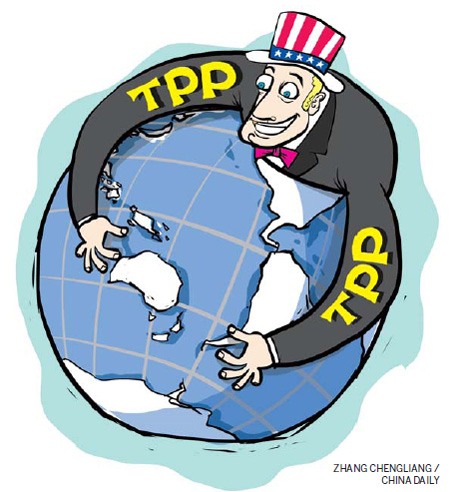

China's participation holds the key for Trans-Pacific partnership

On Nov 12, leaders of nine countries - Australia, Brunei, Chile, Malaysia, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, Vietnam and the United States - announced the broad outlines of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement, which quickly grabbed the headlines and became a topic for many political talk shows across the world.

The TPP has its roots in the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership (P4) Agreement, signed by Brunei, Chile, New Zealand and Singapore in 2005. As the four countries became increasingly disappointed with the slow-paced development of trade liberalization under the framework of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), they tried to form a comprehensive free trade area (FTA) in an effort to advance Trans-Pacific wide economic integration. Since P4's combined economic strength is quite limited, such a free trade arrangement attracted little attention from other nations in this region.

When the Obama administration decided to enter the TPP negotiations with the objective of shaping a regional pact, all of a sudden TPP became a buzzword in international political and economic spheres. In the past two years, negotiations gained momentum: Australia and Peru joined at the invitation of Obama in 2009, and Malaysia and Vietnam became new negotiators in 2010. With strong encouragement from the US, Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda announced in early November that Japan would participate in the negotiations. Japan's new interest in the TPP fuels speculation that the TPP would be dominated by US-Japan condominium.

With 10 (prospective) member states and their combined GDP of $22.44 trillion (2010), the proposed TPP is seemingly poised to become a major building block for Asia-Pacific regional economic integration.

The broad outlines made public on the sidelines of the recent APEC summit highlight some of its unique characteristics.

First, the TPP agreement will be comprehensive. In addition to the traditional merchandise, services and investment, the TPP will cover some new cross-cutting issues, such as regulatory coherence, competitiveness and business facilitation.

Second, the TPP is designed to be more effective and forceful in implementing all sorts of measures, and all the member states are expected to eliminate or at least substantially reduce barriers for trade and investment over a 10-year period after negotiations are completed.

Third, some of the proposed TPP agreement will be bold and intrusive.

In comparison with other types of FTA agreements, which used to carefully skirt some sensitive issues, the nine countries have adopted a proactive approach in addressing some behind-the-border impediments to trade and investment, such as intellectual property, state-owned enterprises, government procurement, labor and environment issues.

Certainly, the TPP is not an altruist device that the US intends to build, for it serves it in the first place. The TPP is a key strategic tool for the US to remain a dominant power in the Asia-Pacific region. Even though successive US governments have realized the increasing importance of the Asia-Pacific in America's national strategy, none of them have fundamentally tilted the strategic balance in favor of the Asia-Pacific rather than Europe.

Obama came to power with a determination to be America's first Pacific President.

In order to cope with the situation that "the world's strategic and economic center of gravity is shifting East", as Hillary Clinton said, the Obama government has adopted a series of concrete measures to bolster its dominance in the Pacific region.

Militarily, it manages to consolidate the traditional "hub and spoke" alliance system, including a plan to send 2,500 Marines to a new military base in Australia.

Economically, the TPP will serve as a convenient tool for the US to fulfill a number of objectives:

1. To reverse a declining trend in US economic influence in the Asia-Pacific region, where the market is huge and growing.

As US Trade Representative Ronald Kirk predicted, the proliferation of trade agreements in the Asia-Pacific region to which the US is not a party has led to a significant decline in market share over the past decade. The US now wants to reverse such dangerous trends and enhance its competitiveness.

2. To achieve Obama's goal of doubling US exports in five years.

Obama made public this ambitious plan in 2010, and the TPP is one of the strategic tools that he could employ to promote US exports, which in turn could create 100 million jobs. Given Obama's possible uphill battle for reelection next year, it is understandable why the Obama government moved so swiftly in facilitating the negotiating process in the past two years.

3. To retake the initiative in regional economic integration negotiations.

In the Asia-Pacific region, some FTAs have begun to take shape and produce positive results, while some are still under negotiation or consideration. At the same time China's role in regional economic integration seemingly looms large.

The US is eager to develop a new model or new regional approach for trade negotiations by forging ahead with an ambitious, high-standard, broad-based FTA agreement that best serves America's interests.

All in all, as Obama confirmed, the TPP "will boost our economies, lowering barriers to trade and investment, increasing exports and creating more jobs for our people, which is my No 1 priority."

Although the TPP could offer potential benefits to the US and other participants, it faces significant challenges. First of all, after battling two brutal and long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and one devastating financial crisis, the bruised US has lost much of its charisma, which once helped to marshal international support and build the Bretton Woods System and other heavyweight global institutions.

The US leadership aims to build a quality TPP that remains to be tested and the resources it could command in this pursuit are far from certain.

Second, the TPP comprises of economic giants and some smaller countries, which are at different development stages and follow different political systems.

Therefore, there is a challenge on how to reconcile interest conflicts and make all the participating nations agree to a comprehensive, and legally binding FTA agreement in such a short period of time.

In addition to the diverse backgrounds of member states that may hinder the TPP negotiations, domestic opposition from any single state also poses a real threat for a quick establishment of a comprehensive, high-standard, broad-based FTA in the future.

Last but not least, the viability of the proposed TPP to some extent hinges on China's support. Apparently, China is left out of the TPP, which will embrace the world's No 1 and 3 economies.

Since China is America and Japan's second and first largest trading partner respectively, and China has already signed the bilateral FTA agreements with Singapore, New Zealand, Peru and Chile, who are also member states of the TPP, China's absence from the TPP not only casts a shadow over this regime's long-term development, but also complicates its own efforts to promote regional economic integration.

The US-backed TPP inevitably makes China feel its impact. In the past 10 years, China successfully walked out of the lingering shadow of traditional self-reliance and proactively pursued FTA deals across the world.

The author is an associate professor with the School of International Studies at Renmin University of China. The opinions expressed are not necessarily those of China Daily.