Time tells for Chang

Updated: 2011-09-30 11:47

By Chitralekha Basu and Mei Jia (China Daily European Weekly)

|

|||||||||

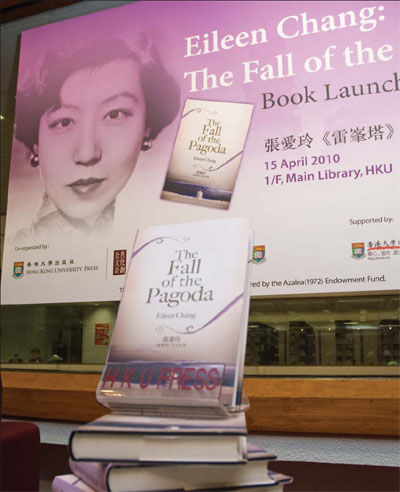

The Fall of the Pagoda was published by the Hong Kong University Press in April last year. [Provided to China Daily]

The author's two-volume autobiographical novels were turned down in 1963, but now they have seen the light of day

Eileen Chang's literary career has been a little like her life story - unpredictable and fraught with high drama. A hugely successful writer in her early 20s in Japanese-occupied Shanghai at the time of World War II - when she wrote some of her best works like The Golden Cangue (1943) and Love in a Fallen City (1944) - Chang failed to secure a publisher for her two-volume autobiographical novels completed in 1963.

She was a US citizen then, having lived mostly in New Hampshire since 1955. Her novels The Fall of the Pagoda and The Book of Change, following the journey of a Chinese girl from age 4 to about 20, from Tianjin to Shanghai to a Hong Kong under siege in 1941, were written in English. But there were no takers for these stories in 1960s United States.

"The publishers here seem to agree that the characters in those two novels are too unpleasant, even that the poor are no better," Chang is quoted as saying in World Authors 1950-1970, A Companion Volume to 20th Century Authors (1975). "Here I came against the curious literary convention treating the Chinese as a nation of Confucian philosophers spouting aphorisms, an anomaly in modern literature."

Half a century later, Chang's predicament continues to dog the present generation of Chinese writers, who are often expected to act as ex-officio spokespeople for traditional Chinese wisdom and represent a political view or the other.

The characters in Chang's fiction - often a decadent bunch of aristocrats, gambling and philandering away their lives, against the backdrop of a raging global crisis in which the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and defeated the British colonial government in Hong Kong - are often seen as projections of the author's own supposed indifference to human suffering and apparent lack of nationalist sentiment.

The publication of The Fall of the Pagoda and The Book of Change, in 2010 - 47 years after they were written and 15 years after Chang's solitary death in her Los Angeles apartment - by Hong Kong University Press could go a long way in busting the myth that Chang was a writer of cheesy romances set off by the kitschy glamour and aura of intrigue in war-time Shanghai and Hong Kong.

Accompanied by a sensitive and thorough introduction by Harvard University professor David Der-wei Wang, the two books are a testimony to the fact that Chang, in fact, took a mature and realistic view of the ravages of war.

The first impulse of Lute, Chang's protagonist and alter ego, and her friend Bebe, after they manage to sell off the rations earned by serving as nurses in the black market, is to go shopping in the silk stores in a near-desolate Hong Kong under Japanese siege.

For a young woman as sentient, well-read and aesthetically-inclined as Lute, this would have been odd under normal circumstances, but that utterly risky and clandestine outing and the unexpected little bounty they find, brings a sense of release to the two young women, who have been tending to wounded soldiers.

As the critic Zhi An puts it: "Eileen Chang has transcended her own time by insisting on not lying to herself, and not lying to others."

Chang was acutely concerned about the downside of a sweeping nationalistic fervor.

"Patriotism was just another religion she could not believe in," she writes of Lute. "But it had killed more people than all the holy wars put together. She was no pacifist, just too fond of being alive."

It is this survival instinct that drives Lute to make use of all her manipulative skills and soft blackmail to win herself a ticket out of Hong Kong at the time of restricted travel.

"The denouement of The Book of Change insinuates that for all the mishaps resulting from the fall of Hong Kong, at least one girl prevails. Lute's triumph is predicated on nothing more than the law of the untenability of human constancy," writes David Wang.

Another reason why Chang's two-part autobiographical novels failed to find favor in the 1960s was because these were perceived as a rehash of a story that had been told before.

"Eileen Chang writes repetitively about the family relations in her childhood, which becomes kind of a psychological remedy for herself," writes Perry Lam in the Shanghai Morning Post. "But for the readers, the idea is not freshly attractive as she was just telling the same story in another language."

She wrote the story of her being confined by her father and stepmother as a teenager, in an essay, titled What a Life! What a Girl's Life! in the Shanghai Evening Post, in 1938. She had almost died of typhoid without medical attention.

She wrote the story again in Chinese (Whispers, 1944). The theme of a repressive, deceitful, self-absorbed, crumbling adult world coming into conflict with that of the unsuspecting, sometimes idealistic young people who get drawn into the morass of decay was the story of Chang's life and she experimented with it in different forms, languages and genres.

It was, as Lam and Wang have pointed out, Chang's ghosts of her past, trying way of exorcizing to come to terms with the hostility and indifference inflicted on her by her own kin as a child.

Besides being one of the most faithful observers of human responses, or the lack of them, to a society in the throes of tumultuous changes before it acquired a well-defined identity as the People's Republic in 1949, Chang is probably China's most consummate bilingual writer.

Something of an outsider to the mainstream Chinese environment - where she couldn't fit in because of her early exposure to an English education, her elitist background and her individualistic impulses - Chang wrote in both Chinese and English with felicity, often reworking the same theme in both languages. Her English flows smoothly, occasionally throwing in a Chinese term or two, adding an ineluctable native charm.

The Fall of the Pagoda and The Book of Change are slightly heavy on inter-textual references to the classics of Chinese literature, what with Lute being a voracious reader.

The title of the first refers to a widely known Chinese myth about a snake princess who falls in love with a human scholar and is held in Leifeng Pagoda as punishment. Lute too is imprisoned for her transgressions and the story ends with her being able to defy the pagoda-like institution of parental control.

The Book of Change refers to I Ching, a philosophical text on the themes of geomantic principles, balance and evolution among others, from antiquity. At the beginning of the story Lute is eager to leave Shanghai to go to England on a scholarship. At the end of it she is back in Shanghai, having braved all odds, older by two years, but now informed by a lifetime's worth of experience, sadder, but also more seasoned. This affirms the cyclical pattern that seems to direct all cosmic movement including that of human lives, as laid down in the I Ching.

"These two English books are not about attractive stories, but about details - details that might be boring," says the critic Zhi An. "Chang was thinking about writing a modern A Dream of Red Mansions (one of China's four great classic novels, by Cao Xueqin, published in 1791) for English readers. She wanted to write about the fall of a family and the fall of her time. But her audience, then, lacked understanding of Chinese culture and tradition."

Things have changed somewhat since then. The first print-run of The Fall of the Pagoda was exhausted soon after its release. Read with its companion piece, the two are like a pair of uncluttered lenses to view China during the war years.