Ancient words blossom into modern art

Updated: 2013-01-07 13:51

By Kelly Chung Dawson (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

In China, the idea that one's character can be judged by the quality of his or her writing is more than an adage. Sloppy handwriting has felled many a hopeful candidate for the country's notoriously difficult official examinations.

|

|

|

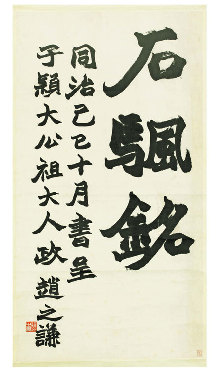

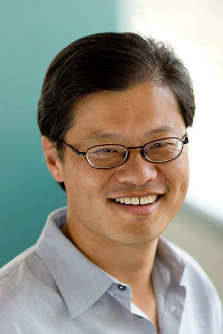

Out of Character reveals the visual power of China's age-old art form. Most of the exhibited works are borrowed from Yahoo Inc co-founder Jerry Yang (below). Provided to China Daily |

|

|

A new exhibition at San Francisco's Asian Art Museum spotlights a form long associated with Chinese elites, who for thousands of years have valued both poetry and the ink strokes in which it's rendered.

Through Jan 13, Out of Character: Decoding Chinese Calligraphy is showcasing 40 calligraphic works borrowed from Yahoo Inc co-founder Jerry Yang and three pieces by US abstract-expressionist painters Brice Marden, Franz Kline and Mark Tobey, who all exhibit Asian influences in their work.

"Calligraphy is alive and well in contemporary China," says Michael Knight, the museum's senior art curator. "It has been China's highest, most respected art form for 2,000 years and it continues to be a source of both fascination and frustration.

"Many Chinese artists deal with it in one way or another even today."

Although the oldest work on display is from the late 13th century, the exhibition includes a playful animation by the contemporary Chinese artist Xu Bing, who is famous for creating thousands of meaningless characters in approximation of the Chinese language.

Out of Character is the first show of Chinese calligraphy in the US since 1999, according to the San Francisco museum. Also included are 15 noted master works, including the painting Lotus Sutra (late 13th to early 14th century) by Zhao Mengfu, and a piece by Dong Qichang.

"You don't have to read Chinese to see the graphical power of the brush in such huge characters and bold strokes," Yang says.

Yang became interested in Chinese calligraphy when a friend suggested he might balance his immersion in modern technology with an interest in ancient art. He began with a hand scroll, and a hanging scroll by Mi Hanwen.

"When I unrolled the (piece by Dong Qichang), the fluidity, ease and beauty of the words he wrote in the late 16th century struck me," the Taiwan-born Yang recalls. "Childhood memories of practicing calligraphy came back to me and I connected to this art form strongly."

His collection now has more than 200 pieces.

"The simple answer is that for me, understanding and appreciating Chinese calligraphy is a journey of discovery, inspiration and fulfillment. The more complex answer is that it has allowed me to bridge the many layers and intricate connections of people, places and time.

"It is also about paradoxes: Calligraphy is outside my comfort zone, yet it feels comfortable and homey. It allows me to understand the past and see the future. It brings me back to my culture and heritage."

For Western viewers, it can be difficult to connect with calligraphic art, Knight says.

"Most Western audiences, when they're looking at a painting, don't even know where the calligrapher started, where the brush was first laid, where it begins and finishes, and what exactly it is as an art form," he says.

One wall in the exhibit displays 85 pages of an album; elsewhere, a hand scroll that's meant to be viewed 81 cm (32 inches) at a time is presented with all 762 cm visible.

The commissioned animation by Xu Bing also attempts to modernize the art form, Knight says. The 18-minute piece, which is the artist's first animation, features thousands of careful drawings presented at 25 frames per second.

"The written language is Xu Bing's art form, and here he is talking about both calligraphy and language in a marvelous way," Knight says. "It's insightful and playful, and deep with lots of literary references."

"People will sometimes say that calligraphy is boring, because they don't understand how it works and it doesn't have visual power. So we've tried to give the pieces as much visual impact as possible," Knight says.

"We want audiences to decide for themselves what they find beautiful in each piece," Yang says.

kdawson@chinadailyusa.com

Related Stories

New Year wishes from Children's calligraphy in China's Hangzhou 2012-12-17 12:02

Ancient Chinese calligraphy and painting works exhibited at Suzhou Museum 2012-12-17 11:58

Art of calligraphy promoted 2012-11-13 09:33

Ancient calligraphy and painting works exhibited 2012-11-08 14:20

Paintings, calligraphies displayed in China's Changchun 2012-11-05 16:04

Today's Top News

Police continue manhunt for 2nd bombing suspect

H7N9 flu transmission studied

8% growth predicted for Q2

Nuke reactor gets foreign contract

First couple on Time's list of most influential

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|