Blanket change

Updated: 2012-02-14 11:20

By Huang Yuli (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

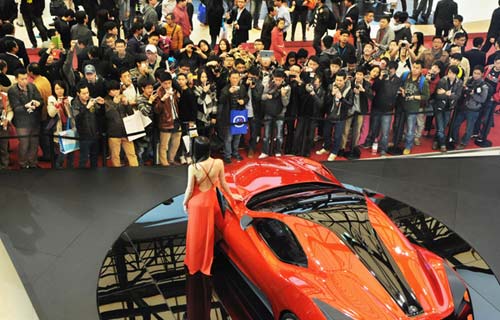

A couple run a family business making cotton quilts in Luoyang, Henan province. Shi Ziqiang / For China Daily |

|

|

Tan Wenge makes quilts with a bow-shaped tool called a jiong that he slings over his shoulder. Huang Yuli / China Daily |

Quilt-making traditions are fading from the social fabric. Huang Yuli reports.

Lu Ping had much to prepare for the marriage of her daughter and local tradition put providing the couple with handmade cotton quilts toward the top of the list. The custom is likely born out of Lixian town's longstanding identity as a cotton production base in Hunan province. Lu made two quilts for her daughter. Lixian resident Guo Fangzhi bought freshly harvested cotton from growers in September and ordered eight quilts from the quilt-makers for her son.

Quilts made by craftspeople are more "reliable", Guo says.

"I know it's really good cotton inside. But I can never be that sure with quilts from supermarkets, even it says its 100-percent cotton."

"You can use them for more than 10 years, and when they lose their fluffiness, you can take them back to the workshop and get them fixed."

Much of the quality is determined by the craftspeople's experience.

Pan Guotai has spent the past two decades making quilts.

"The cotton quality used by quilt-makers is much better," the 46-year-old says.

Pan explains quilt-makers use at least Level 2 quality, while the supermarkets usually use level 5 or 6. Level 10 cotton is the lowest quality.

And craftspeople invest more time and attention to ensuring the cotton is fluffy and the stitching is better.

"And you can customize. Some people like lighter and thinner quilts and use about 3 kg of cotton. Those who like thicker ones can order theirs made with 5 kg."

And handmade quilts are cheaper, selling for about 135 yuan ($21), while supermarkets sell them for about 500 yuan.

Pan started making quilts in his 20s as an apprentice and opened a shop with his wife after mastering the trade.

Pan identifies three steps for quilt-making.

First, cotton is fluffed by machine. Second, the refined cotton is shaped into a massive rectangle with a thread grid. Third, the quilt is milled to blend the thread grid into the cotton.

The first and last steps are most important, Pan says. "The more refined the cotton, the fluffier the quilt," he says.

"The thread and cotton must blend. Otherwise, the thread will likely unravel."

Despite handmade quilts' advantages, Pan doesn't believe the trade will last.

"Nobody wants to learn it," he says.

Pan hasn't been able to find an apprentice in the past seven years. Neither have any of the town's other quilt-makers.

The main reason is the trade doesn't bring in much income. Pan and his wife take an hour and a half to make a quilt and can finish about seven a day on average. They charge 30 yuan to 45 yuan for their work, depending on the quilts' sizes. So, they earn 200-300 yuan a day.

It's also seasonal work that follows the cotton harvests.

Business starts in September and ends in the 12th lunar month, so quilt-makers have about four months of regular business.

"Even those young people who have mastered the skill will give it up if they can find other work," Pan says.

"It's more work than pay. It also produces a lot of dust - usually more than a mask can protect you from. So, quilt-makers face the risk of lung diseases."

But not all challenges to the trade's future are on the supply end.

"Most of our customers are middle-aged or elderly people, who are ordering quilts for their children," Pan says.

"Young people won't bother to buy cotton and go through the rest of the process. They prefer to go to the supermarket, even though it's more expensive. How many quilts will one need, anyway?" he continues.

"And many young people - even in our town - don't even know we quilt-makers exist."

Tan Wenge echoes Pan's concerns about the future of their trade.

The 45-year-old took over his master's business seven years ago, when the man who taught him the craft became too old to continue.

Tan makes quilts the ancient way - without machines.

He instead uses a bow-shaped tool called a jiong that he slings over his shoulder. Tan holds the jiong with one hand and a wooden mallet in the other. Striking the jiong string fluffs the cotton.

And he grinds the cotton with a thick wooden slab that has handlebars.

"I might be the only one in town who still uses the old tools, although the old way makes better quilts," he says.

And using ancient implements slows the process. Tan and his wife need at least two hours to make a quilt, which means less money over time.

Tan recalls that, 20 years ago, quilt-makers only made one quilt a day and focused on ensuring top quality.

But he understands that way of doing things doesn't have much space in an age where time is money, he says.

"Our town's quilt-makers are about my age or older," Tan says.

"Very few young people do this business."

Pan has a daughter and a son. The daughter is pursuing a postgraduate degree in English at Beijing Institute of Technology, while the son is a sophomore at a medical college in Lanzhou, Gansu province.

Neither knows how to make quilts. Nor does Tan's son.

"When we get old and leave the business 20 years later, quilt-making will disappear from our town," Tan says.

Pan agrees. "It's inevitable," he says.

"There's nothing we can do about it. And I don't encourage young people to do this job. It's not worth the hard work."

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|