Chirping for victory

Updated: 2011-11-08 07:54

By Sun Li (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

Two cricket fighting fans stage a fight during the China Cricket Association's Beijing championship. Photos by Zou Hong / China Daily |

Cricket fighting is a world unto itself, with star gladiators enjoying the spoils, including conjugal visits from harems of females. Sun Li reports.

The two combatants scream high-pitched battle cries as they leap toward each other. One slips out of an attempted headlock to flip his attacker over, judo style.

"Attaboy!" transfixed spectators howl.

These gladiators have no weapons but their legs and jaws, exoskeletons for armor, and a glass arena the size of a takeout box for a coliseum.

But not just any cricket can become a prizefighter, Beijing Singing Insects Association secretary Zhao Boguang explains.

"Crickets must be cultivated by masters to become fierce warriors," he says.

The first step is selecting good stock, he says. Shandong province produces the best combatants, as its soil and climate breed the biggest bugs.

"A prime candidate should have large jaws to seize its opponent, dagger-like serrations lining its mandibles to enable it to bite harder and long legs to help it stand its ground when charged," Zhao says.

|

While ordinary crickets cost 10 yuan ($1.60), super soldiers can cost thousands of yuan.

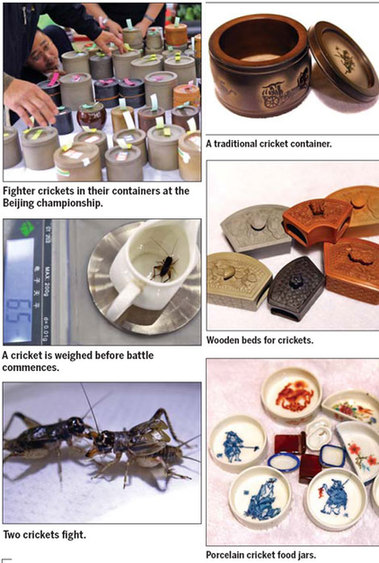

Great gladiators must be treated to banquets of ginseng, crabmeat and sheep liver. They should relish these fine feasts in elaborately carved porcelain jars and digest their meals in a tiny wooden bed.

And these itty-bitty brawlers should enjoy conjugal visits from a harem of female crickets on the night before a big fight. Satisfying their libido, Zhao says, is integral to helping them focus during combat.

But a fighter cricket's life is not merely one of indulgence outside of the ring.

The chirpers are trained by learning to respond to being whacked on their backs and heads by hay strands. It takes about four days to get the rhythm of their maneuvers right this way, Zhao says.

The stakes are high for contestants. Matches usually last only seconds, and losers are unceremoniously dumped, while to the victors go the spoils of more food, females and luxuriant accommodation.

There have already been many losers this year, as the fighting season, which starts when the insects fully mature in late September, ends in mid-November.

"So those that are still in the game are hardened veterans, who have remained undefeated for about six rounds," explains Li Xunjie, a 69-year-old retiree who judged the China Cricket Association's Beijing championship on Nov 6. "More people are enthusiastically watching the ongoing matches, because they're all-star games."

There are about 4 million cricket fighting fans in China, National Office of Pet Services Training Program dean Yuan Wei says.

About 300 companies specialize in producing cricket-fighting equipment nationwide. And annual cricket sales hover around 400 million yuan ($63 million) in Shandong province.

Zhao also operates a cricket-fighting equipment store in the capital's Shilihe fish and insect market.

He believes the culture surrounding the tradition is profound, and offers opportunities to learn a lot about fields ranging from entomology to geology.

Zhao believes the reason cricket fighting's popularity has endured since the Tang Dynasty (618-907) - it was a pastime of imperial aristocrats that later won favor among commoners - is the human pursuit of triumph.

"Obviously, people can't fight in real life," Zhao says.

"But they still want to outdo others. So they manipulate the insects' bellicose instincts to vicariously experience battle and victory."

Cricket farmer Wang Xueqian believes it also contains a strong social component.

"I used to catch crickets with my father and watch them fight for fun," the 55-year-old public servant says.

"When I grew up, I realized it's something that creates and reaffirms friendships."

Wang reminisces about the days when community members would crowd hutong courtyards to watch battles. And he laments the fading of such festivities, as high-rises have continued sprouting from the rubble of traditional neighborhoods.

"But modern monstrosities can't swallow the die-hard practitioners," he says.

"We still stage matches in our homes. And our old friends all come."

While most practitioners are older than 60, some younger fans are chirping about the pastime.

It was 28-year-old Beijinger Zheng Lin's father and grandfather who got him into cricket fighting.

But the finance worker says it was the siren song of the creatures, which he calls "a token of vitality", that fascinates him most.

"The chirping sounds so melodious and makes me feel warmer and less lonely as I walk in the autumn winds," he says.

And he loves the valor of cricket combat.

"It's head-to-head," he says.

"That's true bravery. And crickets stop singing when they lose. That's a true shame."

These are lessons he believes he can learn from these little bugs. "And cricket fighting seems a better way to relax than surfing the Web or singing karaoke."