Iris Chang: A light in the darkness

Updated: 2015-12-14 08:06

By Zhao Xu(China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

Born in 1937, Shau-Jin Chang was age 6 months when his family arrived in Chongqing. Even now, almost 80 years later, he remembers the scene during the bombing raids.

"The Japanese were bombing virtually around the clock. Coming temporarily from the underground bomb shelter, I saw people outside with blood-splattered faces. I was about 6 at the time. However, my father told me that what happened in Chongqing was nothing compared with the suffering and carnage in Nanjing."

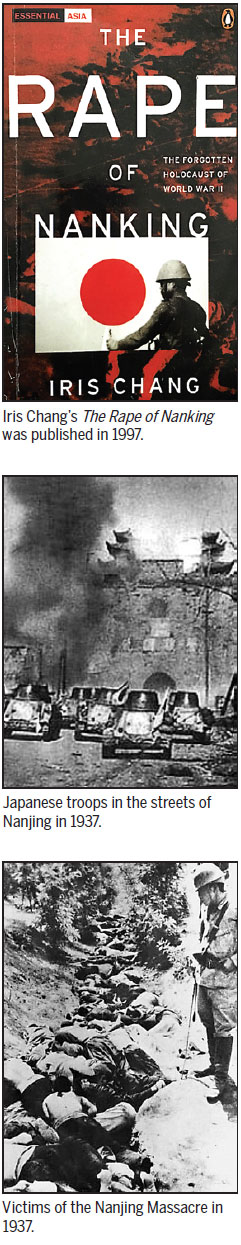

Despite having heard stories about Japan's wartime atrocities, Iris Chang was overwhelmed when she stood in front of poster-sized images of the Nanjing massacre at a 1994 conference in Cupertino, California, sponsored by the Global Alliance for Preserving the History of World War II in Asia.

"Nothing prepared me for these pictures - stark black-and-white images of decapitated heads, bellies ripped open and nude women forced by their rapist into various pornographic poses, their faces contorted into unforgettable expressions of agony and shame," she wrote.

By then, she had graduated in journalism from the University of Illinois, where her parents were both science professors. For the next three years, the budding writer was to plunge into a history that constitutes one of the darkest chapters of World War II, and produced a book that is "almost unbearable to read" but "should be read", according to Ross Terrill, an Australian academic, author and China specialist.

Iris Chang began her research in the US. In the Yale Divinity School Library, she read the diaries of Wilhelmina Vautrin, also an alumnus of the University of Illinois.

Born in 1886, Vautrin, a US missionary, was president of Jinling College in Nanjing at the outbreak of war in China. Turning the campus into a refugee camp, she helped save tens of thousands of Chinese, mostly women, during the massacre and afterward. "How ashamed the women of Japan would be if they knew these tales of horror," she wrote in her diary on Dec 19, 1937.

The stress took its toll, and having witnessed so much violence, Vautrin returned to the US in early 1940. On May 14, 1941, she took her own life.

Retracing old footsteps

Six months after reading the diary, Iris Chang was in Nanjing tracing Vautrin's footsteps, and discovering more about people and stories mentioned so frequently in the older woman's writings.

One of the interviewees was Li Xiuying, who was 18 years old and seven months pregnant in November 1937. She was stabbed repeatedly and was left for dead, until a fellow Chinese noticed bubbles of blood foaming from her mouth. Friends took her to the Nanjing University Hospital, where doctors stitched 37 bayonet wounds.

Unconscious, she miscarried on Dec 19, the day Vautrin made her diary entry.

"Now, after 58 years, the wrinkles have covered the scars," Li told Iris Chang, pointing to her own face, crosshatched with scars.

During her visit to Nanjing, Iris Chang was deeply disturbed not only by the inhumanity of war, but also by what she saw as a failure to mete out appropriate justice, according to Yang.

One of the survivors they visited lived in a room no more than six square meters. The old man was bathing, and the water in the small basin had almost turned muddy. "The way Iris moved her video camera - from the low ceiling to the soot-covered walls and the rubbish-clogged corridors - clearly indicated her mood," Yang said.

According to Brett Douglas, who married Iris Chang in 1991, all the information his wife gathered during her stay in Nanjing, was "distilled and filtered" in the writing process, when she was "working 70-hour weeks".

There was still research to do. After sending out more than 100 e-mails, Iris Chang received a reply from Ursula Reinhardt, granddaughter of John Rabe, a German businessman who, together with other Westerners, established the Nanking Safety Zone in December 1937, saving hundreds of thousands of lives. For the first time, the diaries Rabe kept during the war became known to the world.

From time to time, Iris Chang would call her parents. "She talked about her nightmares and her hair loss," Ying-Ying Chang said. "I told her to stop. But she said no. She said she wanted to speak for those who could no longer do so."

Today's Top News

Merkel refuses cap on number of refugees

China mulls court services in English

Climate talks move slowly

Fosun chairman Guo Guangchang unreachable

Putin, Cameron discuss Syria crisis, anti-terror fight

11 children drown at sea

Unregistered citizens to finally gain recognition

Aging population could shrink workforce by 10%

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|