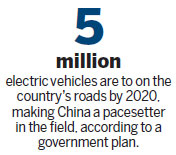

China has the potential to be top market for electric vehicles

Updated: 2015-10-30 07:28

By Du Xiaoying(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

In October 2008, Beijing took decisive action by bringing in a system under which on one workday a week, between 7 am and 8 pm, cars whose license plates end with a particular digit are barred from using the roads.

Then, in January 2011, it introduced a system of bimonthly lotteries for those wanting to buy a new car, a measure that Chengdu, Guangzhou, Shanghai and Tianjin have also adopted. In the first ballot in Beijing, 190,000 or so motorists put their names forward for about 17,500 license plates, giving them about a 1 in 10 chance of success. Predictably, the numbers of those throwing their names into the hat have ballooned, and in August more than 3 million hopefuls vied for just 20,000 license plates, giving them about 1 in 150 chance of success.

With the diminishing odds of winning, desperate applicants are now turning to the separate lottery for new energy car license plates, whose odds are a lot kinder. In August, 8,737 people entered a ballot for 3,333 license plates, giving them a better than 1 in 3 chance of success. However, as the queues for these license plates lengthen, so do the odds of winning.

In April, Beijing, in an attempt to make new energy vehicles more attractive, exempted pure electric cars from the day-of-use rationing system, meaning they can be driven no matter when. The research company Nielsen and the China Association of Auto Manufacturers said in a report in August that the more generous application of license plate rules for those driving new energy vehicles would favorably influence the decision of 16 percent of 700 respondents on whether to buy a new energy car.

However, despite all the best efforts by authorities to make the vehicles attractive, would-be buyers continue to be deterred by their cost, the frequent need to recharge them and the lack of charging stations.

"For example, you cannot drive an all-electric vehicle from Beijing to Shanghai and rely on charging along the way," Jochem Heizmann, a member of Volkswagen's group board of management with responsibility for China, wrote in an essay in May.

"This is because the infrastructure has not been completed yet - and even once it is, the standard may not be universal. To this end, we need dependable, stable technologies. This way, in the future we can channel our development investments in the right direction and contribute toward advancing plug-in hybrid technologies."

In early October, the State Council issued a directive that calls for the installation of electric charging stations to be sped up. Local governments have been taking measures to set up networks of stations, perhaps none more radical than Beijing, which plans to have dozens of stations installed around the city over the next eight months and has decreed that at least 18 percent of parking spaces allocated to new buildings must be equipped for charging posts.

Still, for many of those who have taken the plunge and bought a new energy vehicle, the pace of installing this infrastructure needs to be stepped up, partly because of the growing numbers of new energy vehicles on the road.

"At the moment, charging is the big problem," says Liu Chunshan, 40, of Beijing, who drives a Denza pure electric car.

"Six months ago, it was OK, but now anywhere you go for a recharge you need to line up."

Not only is the number of stations not keeping pace with the number of cars, but their overuse means many are out of order and it takes a long time for them to be repaired.

Li Yanping, 43, an Uber driver in Beijing, who has rented a BYD E6 pure electric car for his work since June, says: "With an e-car, even if there are only one or two cars in front of you, you could be waiting up to six hours."

It can then take between 90 minutes and three hours to charge the car, depending on the voltage of the post, he says.

Today's Top News

Two-child policy to add $12b in consumption

China to buy Airbus jets in $17b deal

China to allow two children for all couples

China's central bank dismisses QE rumor

Chinese premier holds talks with German chancellor

Refugee crisis continues to create rift between pro-Europeans, Eurosceptics

Rescue operations continue in quake-stricken Afghan provinces

Dutch King receives Dutch rabbit with Chinese characteristics

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|