Prodigies seeking a class act in universities

Updated: 2011-11-14 07:29

By Wang Yan and Chen Jia (Agencies)

|

|||||||||

Athin but fit figure at 5 feet 10, he looked no different from other college students. His shyness and unguarded manner, however, gave him away. Zhang Xinyang, from Panjin in Liaoning province, entered college at just 10 years of age, a record in China. Now 16, he is pursuing a doctorate in mathematics at Beihang University in Beijing.

|

|

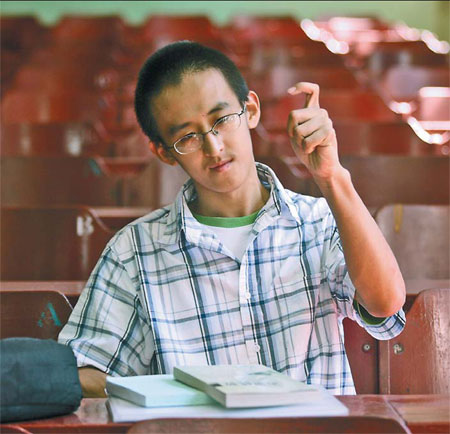

Two young teens spend time in study hall after enrolling this year at the University of Science and Technology of China. Every year about 3,000 apply to the School of the Gifted Young and about 50 are admitted. [Photo / China Daily] |

But his current goals are not academic. "An apartment in Beijing, a good job and a Beijing hukou," (permanent residency) he said.

Neither his youth, academic ability or even future paychecks can guarantee such "basic needs to maintain the dignity of a newcomer to a big city", he said. He figures that's up to mom and dad.

He requires his parents' money to buy an apartment, which he hopes to be "about 90 square meters with two bedrooms, meaning about 2 million yuan ($315,000)".

"Providing a place for the child is the parents' responsibility," Zhang said. "They wanted me to come to Beijing for university, and that's what they need to pay for their own choices."

Raising a child prodigy gives parents reason to feel proud, and apparently that's what many hope for.

About 1,400 high school students across the country applied this year for 100 to 130 openings in a program for gifted youths at Xi'an Jiaotong University. The number has been increasing by 200 to 300 annually in the past few years, according to data from the university.

At the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC), about 3,000 apply to the School of the Gifted Young each year. About 50 are admitted to the school in Hefei, Anhui province.

The number is controlled so the university won't receive excessive applications, according to Chen Yang, the school's executive dean. "We take no more than 10 applications from each high school across the country."

Parents have solid reasons to get excited for the chance. Since the gifted program was launched in 1978, USTC has graduated 1,223 prodigies, among them many big names.

For example, Zhang Yaqin was 12 when he was admitted in the first class of USTC's School for the Gifted Young. At 31, he became a fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Now 45, he is the corporate vice-president of Microsoft Corp.

Guo Yuanlin, who also enrolled in 1978, is vice-president of Tsinghua Unisplendour Corp Ltd.

Academic achievements are also remarkable. Six of the program's graduates are professors at Harvard University, while many are teaching at top universities including Tsinghua, Peking and Yale, according to Chen, the executive dean.

"Among all graduates, 60 percent have gone abroad for further studies, while 30 percent attended grad school in China and 10 percent landed jobs" right after earning their degrees, he said. "Graduates of the School of the Gifted Young have generally higher achievements than their peers."

Out of balance

Success didn't come easily. In the past 30 years, 13 universities in China opened programs for gifted youths but only two remain, at USTC and Xi'an Jiaotong. Those that withdrew include Tsinghua, Zhejiang and Shanghai Jiao Tong universities and Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

|

|

Zhang Xinyang, 16, says he usually gets up at 9 am to begin his day's college work at 10. He is pursuing a doctorate in mathematics at Beihang University in Beijing. [Photo / China Daily] |

Shanghai Jiao Tong quit enrolling prodigies in 2001 for "unsatisfying qualities of the students", according to a report then by Shanghai Morning News.

Qian Qicheng, who was deputy director of admissions at the time, said that in the program's early years, prodigies showed high learning abilities and self-motivation. Starting in 1992 and 1993, however, exam-oriented education methods led to rigid and imbalanced students with high scores and immature mentalities.

"Most of the students are good in mathematics but weak in humanities and English," Qian said.

That's how Zhang Xinyang, the doctoral student in math, describes himself.

"My major is useless in getting good pay in the future. I chose it out of interest. Plus, there is no strong connection between one's income and academic degree. Many of the things learned at universities cannot be applied in society."

Zhang didn't like the idea of choosing a major for practical reasons, but he said it's his parents who should worry about practical issues.

He said he would rather take a low-salary job at an air-conditioned research institution than a high-salary job that requires competition and struggle, because it's "more comfortable and simple".

Zhang doesn't like being called a genius. "I'm nothing outstanding. I know how to pass exams." He also has no desire to study abroad, where "academic requirements are stricter and my basis is not solid enough to face the challenges."

His plan for the future is to carry out research in mathematics, but some basic problems should be solved first. That brings him back to housing.

"Leasing a place won't be the solution," Zhang said, his teenage tone firm and inarguable. "What's the point of getting a PhD if I cannot even afford an apartment after graduation?"

Whether his civil servant father and schoolteacher mother could afford such an apartment is not Zhang's concern. "If they can't, I'll just go back to my hometown."

When reality hits

Like Zhang Xinyang, many gifted youngsters have trouble coping when they find that changing fate through knowledge is a lie in China, said Zhang Yutang, a retired professor of education science at Sichuan Normal University.

He said there are two kinds of Chinese parents who are passionate about sending their children for higher education: rich people who need successors to their fortunes, and grassroots parents who want their children to become kings of kings.

"They were taught the same value about success in schools, but society would label them differently when they face reality," he said.

Parents of ordinary means and social standing devote much more effort to encouraging their children to study hard, jump grades and earn PhDs, Zhang Yutang said. They also show more disappointment when their children don't achieve those things.

Many young people of poor families couldn't get a well-paid job because their families have few social connections, he said. They also couldn't afford to buy a home in a big city.

"In this case, anger is a natural reaction for a gifted youngster from a poor family who is fed up with the pressure caused by unfairness, and he begins to blame parents for their unrealistic expectations," he said.

What's best?

Xiong Bingqi, deputy director of the private, nonprofit 21st Century Education Research Institute, sees the key to educating the gifted young as teaching according to the students' abilities.

"We always promote an education mode for a group rather than individual. In this sense, developing schools for gifted young indicates that society is unable to provide balanced education resources for every child," he said.

"It is not about how the gifted young have a special channel to access higher education, but to discuss that every child deserves a specific education plan designed by the school."

Chen Yang, the executive dean at USTC, thinks along similar lines. "Successful education is not to give every student the same stuff, but to graduate them into distinctive individual talents."

Choosing, guiding

In the elite prodigy programs, developing those talented students begins with selecting the right candidates.

USTC takes applications from students younger than 16, and allows the most qualified to take that year's national college entrance exam. Based on their exam scores, about 70 to 80 students will be invited to the campus in East China for a second round of evaluation.

Professors in the School for the Gifted Young will conduct personal interviews, and some may give spot lectures and question the applicants afterward to test their learning ability.

The chosen students, ages 12 to 16, spend their first year together studying basic subjects, which allows them a better idea of what's best for the future. Then they decide on a major and enter the mainstream of university students.

In the past 33 years, Chen said, 13 or 14 students dropped out of the school. "Almost 99 percent of them were addicted to video games."

To supervise and guide these younger students, a teacher is assigned to take care of each group. One of them is Lan Yuan, a mom-like 37-year-old. "Supervising a young prodigy class requires more patience and care" than would average students, she said.

Freshmen are not allowed to take personal laptops to school, and Lan often takes random walks to the university computer centers to make sure her students are not spending too much time on video games.

News reporters are not allowed to conduct individual interviews with students so they won't feel too proud or too pressured.

"Another important thing is to have thorough and frequent talks with my students about life, study and the future," Lan said. "We hope to get them ready for society before they leave here."

How, not if

For executive dean Chen, developing schools for the gifted young is not a matter of right or wrong, but rather how to make them better.

"It's no surprise that China has a certain amount of gifted young among its large population. Education for such a group will always be a topic. There is a supply-demand relationship out there.

"A single positive or negative example doesn't tell the whole story. People should look at the overall picture before making judgments. I hope society will create a fitting environment for them to learn and grow."

Jin Huiyu and Cheng Shuying contributed to this report.