Journey to the spicy west

Updated: 2016-01-29 07:51

By Pauline D. Loh(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

"For the people, food is heaven," said Sima Qian, an historian from the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24). Today, these words still ring true. The Chinese people's respect and passion for food is firmly entrenched in the cultural landscape, with a culinary scene that reflects the vast geographical footprint of the world's most populous country. Pauline D. Loh offers a view from the table.

The heat rises as the galloping gourmet travels west in China. Chuan cuisine of Sichuan province and its southwestern neighbor, Yunnan, uses copious amounts of China's only native spice, the tongue-numbing prickly ash berry known to the world as Sichuan peppercorn.

Together with the red chili pepper, which was introduced to China in the late 16th century, prickly ash berries became synonymous with the predominant mala flavors here.

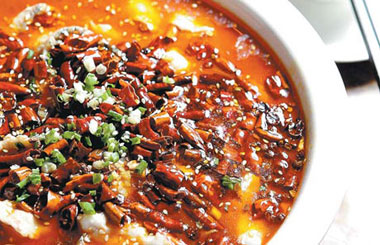

And no dish is more representative than hotpot, with its simmering layer of red oil. Platters of thinly sliced food are placed around a communal pot of boiling stock and diners select their choice of meat or vegetables and cook it to their liking.

The secret is in the spice mix used to flavor the oil, and individual chefs jealously guard their own special blends.

Generally, at least two different varieties of dried red chili peppers are used, one for the color and one for the heat. Chefs have been known to add even more varieties to layer and add depth of flavor.

Then, the most important ingredient is added - Sichuan peppercorns, of which there are just as many varieties. The dried red berries, a lovely dark maroon, are more mellow, while the green berries are chosen for their almost anesthetic qualities. They all numb the mouth. More spices, such as fennel, cumin, nutmeg or star anise, go into the mix, which is then toasted and cooked in rendered beef fat.

This sizzling oil is prepared at the end of the day and allowed to mature overnight, ready for the hotpots to be served the next day. The rest of the kitchen does the slicing and dicing of ingredients.

The hongyou huoguo, or red oil hotpot, is served all over Sichuan, although there are countless regional variations when it comes to heat levels and the food that is finally cooked in the broth.

Beef is a popular protein, cut into paper-thin slices for easy cooking, as is beef tripe. Sichuan diners love tripe so much they name them according to the stomachs they come from.

Another unusual off-cut is the lining of the esophagus, a crisp layer of beef muscle that is enjoyed purely for its texture. It has little taste, although that matters little in a highly spiced hotpot.

Goose or duck intestines are also happily dunked into the pot. They take a lot of cleaning, but Sichuan kitchens have perfected this art.

Hotpot lovers also enjoy cooking cubes of duck blood in the pot, especially since the black pudding soaks up the spicy broth like a sponge.

All is not lost for those with zero tolerance for spice, though. These days, most hotpot restaurants offer a yuanyang pot, named after the inseparable mandarin ducks. Shaped like the Taoist yin and yang symbol, twin pots spoon lovingly next to each other, one with a mild white broth, the other holding the famous red stock.

Not every dish in Sichuan is centered on hotpot. There is also the famous bean curd dish called mapo doufu. Reputedly created by a lady who suffered from a serious attack of acne, which left its marks, this tofu dish is another classic with an international reputation. Tender cubes of soft tofu are cooked in a mala mix of peppers and Sichuan berries. Sometimes, minced meat is added to fortify the dish.

Just as popular are gongbao chicken, prawns or pork dishes. Gongbao describes a style of cooking that creates a sweet and spicy sauce. Fat chili peppers are deep-fried to release their smoky fragrance, added to the meat and stir-fried over a fiery wok with the rest of the condiments. A scattering of peanuts add crunch.

Sichuan cooking has been much tempered in its long journey from home to the Chinese restaurants abroad. While Cantonese dishes are best known in gourmet circles, chuan cuisine is also finding addicts abroad.

A Sichuan native would sniff at the watered down heat of the menu, but it is a gradual introduction until the serious gourmets can head to the land of the pandas for the real thing.

Dishes to try in Sichuan:

Hotpot

Do not be intimidated by the glowing layer of floating red oil. It flavors the soup and keeps it bubbling, and you are not drinking it up, only using it to cook. If there is just the two of you, order the twin pot so you have a choice of mild or spicy. If there is a group, most restaurants thoughtfully offer a pot with partitions so you each have your own little piece of heaven.

In a hotpot meal, diners normally cook the meat first, adding the various bean curd products next, and finish up with the vegetables.

Gongbao chicken

Probably the most popular dish on the menu. This sweet and spicy dish has found international acclaim. Cubes of chicken breast are blasted over high heat and tossed with deep fried chili and peanuts. In Sichuan, the locals prefer a more down-to-earth version. Chicken is chopped into bite-sized chunks, bones and all, and stir-fried with lots of chili peppers and Sichuan peppercorns. They call it lazi ji, or pepper chicken.

Mapo doufu

Arguably the most famous bean curd dish from Sichuan, this dish is a study in taste and texture contrasts. The bland-tasting tofu is spiced up with a numbingly hot sauce, while barely perceptible grains of minced meat deliver a satisfactory crunch as the tofu melts in the mouth.

Next week: An eastern renaissance of art in food

Today's Top News

New China-led bank 'will be inclusive'

Horizons expand for Chinese companies in France

Negotiating political transition in Syria 'possible'

Man arrested with handguns at Disneyland Paris

Record number of Chinese tourists visited UK in 2015

Foreigners fill in Spring Festival courier gap

UK adventurer dies on solo journey

Families of expats in China can stay longer

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|