A symbol of preservation

Updated: 2012-02-18 09:25

By Raymond Zhou (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

The leveling of an old-style house in Beijing that was the dwelling of a prominent couple of architects and preservationists has provoked a public outcry.

The demolition of the courtyard house he rented from 1931 to 1937 must have been the last thing Liang Sicheng worried about while he was alive. But for a nation that once sneered at his foresight and calls to protect heritage architecture, it is an ironic symbol for the inexorable advance of the bulldozer and the ravaging of everything that stands in its way.

|

|

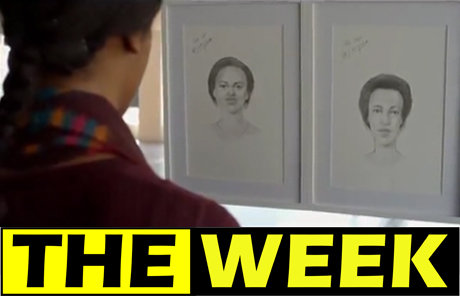

Liang and Lin in 1931 when the couple moved from Shenyang, Liaoning province, to Beijing. |

Liang Sicheng (1901-72) and his wife Lin Huiyin (1904-55) were the most distinguished of modern Chinese architects. Among their creations are the national emblem of the People's Republic of China and the Monument to the People's Heroes on Tian'anmen Square. China's national award for architectural design is named after Liang.

The man who tried to save old Beijing

More important than that were his efforts, though failed, to protect the city walls of Beijing. In the early years of New China, Liang proposed to leave the old city intact and build a new one to its west. Later, as the city walls fell victim to political winds, he risked everything to save the walls first, then only the wall gates. The then Beijing mayor branded him "despotic" as they engaged in a tug of war over the fate of the old structures.

|

|

The former house of Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin in Dongcheng district of Beijing was demolished in January. |

As they were torn down, Liang lamented: "Whenever a city gate was razed, it was as if they were slicing a piece of my flesh; whenever a section of the wall was gone, it was like skinning me."

We can't appreciate the void because very few of us have seen old Beijing in its authentic majesty, but we can probably understand Liang's frustration. He must have felt like the proverbial bug that tried to stop a rumbling carriage. Yes, he was crushed mercilessly. And we're all poorer for it.

"In 50 years, you'll know I'm right," Liang said famously. How prescient those words seem now.

In a sense, people today are trying to repeat on a very small scale the epic battle Liang attempted but tragically failed - and also to honor him in the process. Of all the residences he inhabited, the house at 24, Beizongbu Hutong, Dongcheng district of Beijing, stands out for two reasons: It was during the Liang couple's stay here that they studied and confirmed the dates and value of many historical works of architecture.

Sure, they conducted their scholarly research in the field, away from home. But while they were in Beijing, their residence served as a salon for the city's literati, attracting luminaries like novelist Shen Congwen and philosopher Jin Yuelin.

As Shan Jixiang, former director of the State Administration of Cultural Heritage, elucidates: "The emphasis should be placed on the transcendental, cultural and social values of an old residence, rather than purely on the architectural quality and artistic value."

Preserving Liang's old residence is tantamount to holding on to what he stands for: treasuring the tangible and immovable objects that were bequeathed to us by our ancestors and cement our cultural identity. We have made so many blunders before. Can't we save just this little piece of old Beijing?

Hutong in ruins

Large swaths of hutong (narrow lanes) and siheyuan (courtyard houses) have already given way to canyons of high rises. In the old days, when Chinese were barely skirting the poverty line, these old buildings, often rundown and crammed with a dozen or more households in a space designed for one, were perceived as eyesores. They do not have indoor plumbing, flush toilets or other modern amenities. People in the 1980s were eager to move out and into apartment buildings.

But the rapid rise of living standards and growing exposure to outside influences have awakened in us the intrinsic value of these uniquely Beijing residential forms. It did not take long before they crumbled in large expanses in the face of urban renewal.

Today's Top News

President Xi confident in recovery from quake

H7N9 update: 104 cases, 21 deaths

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|