A symbol of preservation

Updated: 2012-02-18 09:25

By Raymond Zhou (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

Nationwide, the scene of destruction is multiplied hundreds of times as anything that obstructs the maximizing of profits is treated the same way so-called "class enemies" were dealt with in an earlier era.

If you talk to real estate developers and those who share their interests, you'll hear something different: These old buildings are invariably in ramshackle conditions, violating fire codes and otherwise not up to modern standards of safety or comfort. But they conveniently omit the fact these buildings tend to occupy large tracts of prime land, and their existence in the current mode will block the developers from realizing the highest profits from the land.

These people will be quick to add that they love traditional Chinese architecture more than anyone. As a matter of fact, they will rebuild this or that structure exactly as it looked in its most glorious days, but with reinforced beams and concrete pillars covered with wooden panels. In other words, they want the best of a theme park and a museum: seemingly ancient buildings with all the trappings of modernity.

That said, not all the "fake antique structures" are monstrosities. Some are tastefully designed and do not claim to have historical significance.

Where the famous once dwelt

The same contradiction manifests itself in some people's attitudes toward residences of the famed. On the one hand, the drive to raze old buildings rarely spare those surrounded by the luster of the distinguished residents, on the other hand there is an urge to associate a place with the big names of yore. In recent years, some local governments have ventured so far as to fight for the "official hometown" of fictional characters that surface only in novels or fairy tales.

One village I visited in 2011 constructed a new house it claimed to be the ancestral residence of an ancient general, in order to "enhance our cultural gravitas", to quote the village chief. But to his chagrin, he later found out another village in a nearby province had already claimed the same general to be their "native son".

What is the appropriate level of protection for old residences with historical value? Do we have to turn every one of them into a mini-museum? The cultural heritage bureaus can designate these buildings, but they usually do not provide the financial wherewithal for upkeep or protection. That is why local governments often take the side of developers.

Indeed, a few of these buildings can be turned into tourist destinations, but most do not have that potential. For those with low historical value and low tourism promise, some kind of middle ground should be found between indiscriminate demolition and strict protection. In this heyday of economic growth, it is unfeasible to expect the ubiquitous stipulation of "maintain it as it is" to counter the visual blaring of "chai!" (tear down).

Maybe some buildings should be allowed indoor renewal while keeping the facade. Others can leave the ground floor for public viewing with private spaces reserved for current owners.

One thing that can be done without too much cost or hassle - but with thorough research - is to place small plaques on those buildings once resided in by prominent citizens of the country or city. Just the name, the profession and the dates of stay will suffice.

Imagine how much a casual passerby will feel walking down the street with such "annotated" buildings. It'll be like walking down a history book.

Getting back to Liang Sicheng, who was the uncle of Maya Lin and the son of the great Liang Qichao. The public gets emotional about his home partly because most people who are not part of the intelligentsia learned about him and his love story through a wildly popular television soap opera.

Suddenly this pioneer of Chinese architecture and its preservation was humanized. You see history condensed in and refracted through one renowned family. That adds to the intangible value of his erstwhile abode. If only the people in charge of developing that property knew what an added asset that is.

|

|

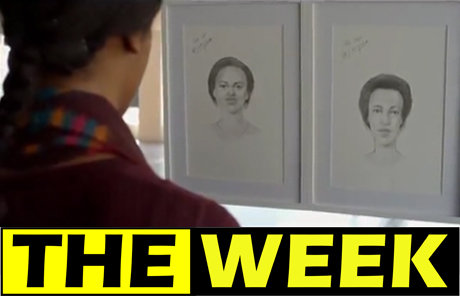

A 2009 photo shows a part of the former residence. The demolition proceeded on and off till December 2011, when the house was listed by the State Administration of Cultural Heritage as an "immovable cultural relic". |

Today's Top News

President Xi confident in recovery from quake

H7N9 update: 104 cases, 21 deaths

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|