'Oldest warrior' defends heritage

Updated: 2016-02-26 08:59

By Liu Xiangrui(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||

|

|

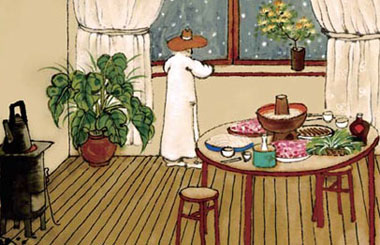

A 91-year-old in Central China is working to revive the endangered craft of making woodblock prints for Spring Festival

As a former child apprentice who is now a nationally recognized master, Guo Taiyun has seen firsthand the ups and downs of the centuries-old craft of Kaifeng woodblock printing.

The 91-year-old has lived through the glory days of the prints that once defined Chinese New Year and the challenges of modern times.

Starting in the Song Dynasty (960-1279), making and putting up handmade woodblock pictures used to be an essential part of the Spring Festival celebrations. Yet with rapid changes over the past few decades, the custom gradually faded until recent attempts to revive it, which have including listing it as a national intangible cultural heritage in 2007.

Technology company Alibaba has launched a crowdfunding project to help promote such old crafts. Through it, craftsmen like Guo create works based on new designs, incorporating popular elements. When photos of the Spring Festival prints were uploaded online in January, they drew huge public interest. So far, the funds raised for woodblock printing have surpassed 50,000 yuan ($7,600; 6,900 euros).

"I'm so glad it's catching public attention again," Guo says of woodblock printing, a cultural signature of Kaifeng, which is a city in Central China's Henan province.

Born to a poor family, Guo, who didn't go to school, was hired after his father died as an apprentice, at age 13, by a shop in Kaifeng that made and sold the prints. "I didn't starve, and I expected to make a living from it later," he recalls.

During the first four years, he observed experienced craftsmen and was able to learn the different steps in the craft, from dyeing the paper and printing to carving woodblocks, which he says is the most difficult part.

"Facial details of figures are the most important. If a face is not lively, the block is useless."

Making pictures for Chinese New Year was a profitable business in the 1940s and there were numerous workshops of various sizes in Kaifeng. The shop Guo worked for employed 80 people during the peak time.

After his apprenticeship, Guo left the shop to open his own small workshop. "It was a good business. I could support my family of seven for the entire year by working for only three months. Even the poorest families would put up new year pictures, which were even more important than having a good meal."

As the industry slowed in the 1950s, Guo had to do different jobs to make a living, but in the early 1980s, when the government took steps to protect the craft, he and other professionals were invited to work on a project that aimed to collect, repair and sort woodblocks and other materials related to the craft from different periods.

By writing a detailed account of the craft, the group has helped protect the endangered art, winning praise from many scholars.

In recent years, Guo has personally won many honors for his contribution to the craft, including being named as a representative inheritor of national-level intangible cultural heritage by the Culture Ministry in 2007.

Institutions such as the National Art Museum of China and the Capital Museum have collected his works, and he has also been invited by countries such as Singapore and the United States for exhibitions, performances and cultural exchanges to promote the craft internationally.

However, Guo says he is an ordinary craftsman who cares more about the fate of the craft than the honors it fetches him.

He has started working with the research and protection center for woodblock pictures at a Kaifeng museum, where he is mentoring three apprentices to pass on his skills.

"He's very strict and pays attention to every detail of the process," says Cai Ruiyong, one of Guo's students. "He spares no effort to pass down what he has learned about the craft over his lifetime."

Guo has participated in many cultural events around China with his apprentices to promote the craft.

"I'm proud to be the oldest warrior fighting to protect it from disappearing," he says. "I feel it's my mission to help society revive the craft."

liuxiangrui@chinadaily.com.cn

Today's Top News

Points of view

Small island makes a big difference

Rubio, Cruz gang up on Trump in debate ploy

'Invented-in-China’ products to the fore at MWC

Beijing edges NYC as home to most billionaires

110,000 refugees, migrants reach EU by sea in 2016

Tech giants reveal 5G innovations in Barcelona

Mechanism to be built to monitor ceasefire in Syria

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|