Life as a living doll

Updated: 2013-08-07 07:17

By Liu Zhihua (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

A wedding ceremony is one of the highlights for osteogenesis imperfecta patients as more than 300 sufferers gathered in Beijing on Sunday. Photos by Zhu Xingxin / China Daily |

|

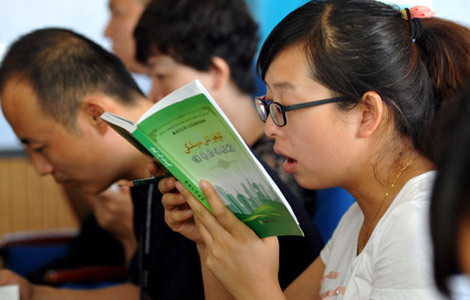

Wu Yulinglong, a 6-year-old from Shaanxi province, joins a drawing contest organized by China-Doll Center for Rare Disease. |

|

Jiang Yingxi, from Jiangxi province, performs the erhu (Chinese two-string fiddle) at an event in Beijing. |

About 100,000 people in China suffer from osteogenesis imperfecta, a genetic and inherited disorder characterized by brittle bones. Liu Zhihua finds out what life is like for sufferers of this cruel affliction.

Six-year-old Wu Yulinglong, a girl from a small county in Hanzhong city, Shaanxi province, looks like a 2-year-old. Her limbs are thin and her legs are so deformed she can barely walk.

"When she was a baby, her bones just broke for no reason," says her father Wu Liang. "We dare not hold her for fear of hurting her."

The girl is one of about 100,000 "china dolls" in the country. The term is used to describe those who suffer from osteogenesis imperfecta, a genetic and inherited disorder characterized by fragile bones.

According to China-Doll Center for Rare Disease, a nongovernmental organization, 70 percent of sufferers live in less-privileged rural areas.

Their bones break easily without any specific cause, and an individual can suffer dozens to hundreds of significant fractures in a lifetime, leaving not only pain but also bone deformity.

A survey report recently released by the center shows that although situations vary, "china dolls" face similar problems in life - poor access to medical care, education and job opportunities.

"Osteogenesis imperfecta is treatable. With timely and efficient intervention, OI children can grow up healthily to live a normal life," says Wang Yi'ou, founder and director of the center, who is also an OI patient.

"But, it is a pity that for the majority of OI patients, it is often too late when they receive diagnosis and treatment."

Wu Liang says in the first two years of her life, his daughter suffered from dozens of fractures and developed deformities as she grew up.

The girl would fracture herself even while lying in bed. Local doctors were clueless about the condition.

When the girl turned 3, doctors in a hospital in Xi'an finally made a diagnosis: She became the hospital's first OI case.

But doctors told the father there was no treatment, nor hope for recovery.

The girl's deformity developed rapidly. Although she's obviously smarter than her peers, she was refused by kindergartens and schools.

Last year, she finally underwent OI treatment in a hospital in Tianjin, with the help of Wang's center, which the father chanced upon when surfing the Internet.

Currently, to increase bone density and reduce the number of fractures, the girl receives drug infusions every three to four months, costing about 2,000 yuan ($326) each time.

The father also plans to send her for surgery to correct her deformity.

Wu Yulinglong is luckier than many OI patients in China as her family is able to afford her treatment.

OI is a lifelong condition and needs continuous treatment, including medication to increase the density of the bones. Otherwise, the bones and muscles will deform rapidly, especially during childhood.

But few hospitals in big cities know how to treat OI, let alone those in less-developed rural areas, according to Qi Ming, a genetic diseases specialist with Zhejiang University, who is also a professor with Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Rochester University in the United States.

He says in many developed countries, such as the United States, the cost of OI treatment is covered by various medical insurance programs.

There are also a lot of nongovernmental organizations and foundations engaged in activities protecting and helping OI patients, such as funding for OI-related research and launching legislation campaigns to protect the interests of OI patients. But there are few in China, Qi adds.

In addition, the high cost of treatment and low insurance coverage prevent most patients from getting medical care.

Without treatment, OI adults can only grow to the height of a young child, with bowed limbs and protruding chest bones. Most of them are not able to move around without crutches or wheelchairs.

The condition also affects their hearing, teeth and blood vessels.

"It is a vicious circle," says Wang Lin, 26, an OI patient from Dalian, Liaoning province.

"Without money and treatment, we will become disabled. No schools are willing to accept a disabled child, and we have to self-study, or remain illiterate.

"When we grow up, we cannot do labor work because of our physical condition, and we cannot obtain good positions in companies because of lack of education. As a result, we earn too little for a living, not to mention to pay for treatment."

Wang Lin works as a receptionist in an advertising firm. But her other friends who suffer from the same condition are unemployed.

"Society should be more aware of the sufferings and needs of OI patients, and extend a helping hand to them," Wang Yi'ou says.

Contact the writer at liuzhihua@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily 08/07/2013 page19)

Today's Top News

PV firms face risks despite EU deal

China central bank continues liquidity injection

Small firms should also think global

NBA courts Sina Corp

Govt to court private capital

Snowden obtains formal registration

EC denies delay in telecoms probes

Two more firms recall milk products

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|