The groves of academe

Updated: 2011-11-17 07:57

By Chitralekha Basu (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

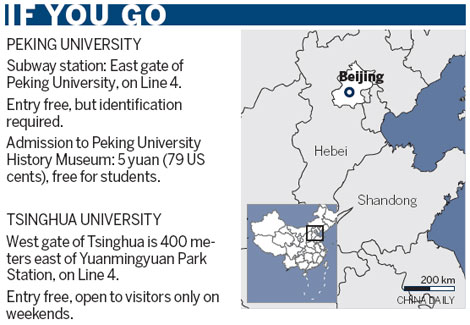

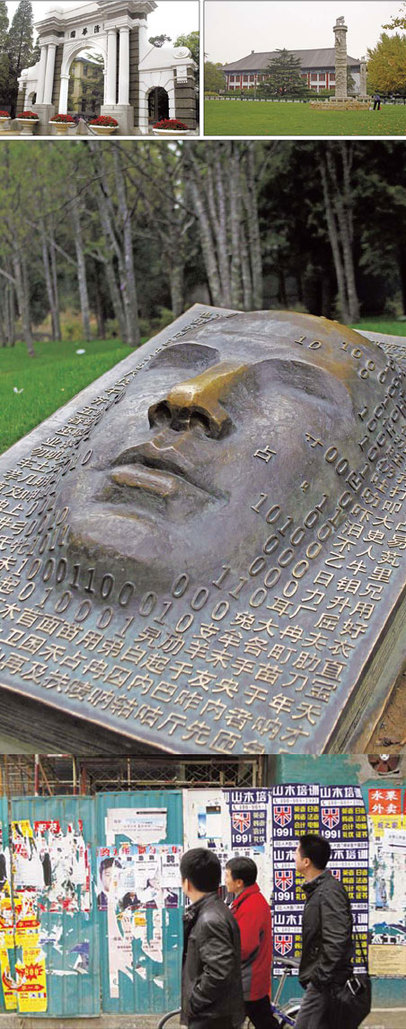

Clockwise from top left: The old marble gate to Tsinghua University, one of the country's top educational institutions. A pillar from the Old Summer Palace in Peking University that survived vandalization during the Opium War. Unique sculptures can be found in every corner of the campus at Tsinghua University. Peking University's construction areas are barricaded by corrugated sheets that are plastered with adverts. Photos by Feng Yongbin / China Daily |

Peking University and Tsinghua University are not just Beijing's top seats of learning. They are also picturesque and well worth a visit. Chitralekha Basu takes a stroll.

Before the blustery winds from the Arctic arrive full throttle and denude the trees in Beijing of their last leaves, this is your chance to check out fall in its many-splendored glory. Forget the obvious destinations like Fragrant Hills, Diaoyutai's "Gingko Road" and Baiwangshan Forest Park, where people go to catch the falling golden autumn leaves. If the idea of combining the study of nature with that of Chinese history appeals to you, the good news is that some of Beijing's finest parks are located in its groves of academe.

Two of Beijing's oldest universities, and still its most influential seats of knowledge - Peking University and Tsinghua University - could well double as veritable tourist destinations. These campuses are replete with memorials, artworks, museums and architectural styles spanning at least 100 years of Chinese history.

Located within a kilometer of each other on the way to Summer Palace as you go northwest from downtown, these two premier institutions have plenty to satiate one's thirst for history and aesthetics.

This is the season when the schools roll out an egalitarian yellow-carpet welcome for whoever will visit - a layer of golden gingko leaves paving the roads and meadows with gay abandon.

To those who lament the gradual disappearance of the generic Beijing bicycle from the city's roads, I would recommend a walk around Tsinghua's sprawling park.

Cradled by the iconic black dome of the Old Auditorium on the north and Tsinghua Xue Tang on the east, the green patch is outlined by an impromptu border comprising a few thousand bikes. The Old Auditorium, now the inspiration for the university's centenary logo, is a mix of European and Greco-Roman styles. It has a red brick body with white marble columns defining the entrance.

Tsinghua Xue Tang, a low-rise two-story structure built in European neo-classical style, is the oldest on the campus. Classes have been held in it since 1911, the year the university was founded. The money came from the royal coffers as Boxer indemnity paid to the United States and was used to build a preparatory school for students to be sent to the US.

On the day I visited, there were men in cheongsams shooting a period flick against its majestic, charcoal black-and-white facade.

About 500 meters southwest of this building - built in 1909 and rebuilt again in 1990 following the original design of Corinthian columns and stately arches - is the spectacular new History Museum, opened recently as part of Tsinghua's centenary celebrations.

One wing of this never-ending edifice is circular, like a drum mounted on stilts, with shark-teeth-shaped glass windows lining the circumference. Besides the incredible range of archival material it contains, there are state-of-the-art multimedia presentations.

Near the west gate is the Chinese block, with generic pagoda roofs, trellised windows with geometric patterns and covered corridors with roofs supported by wooden beams - hand-painted in fluorescent shades of peacock blue, green and gold - linking the rooms. Gong Zi Ting, or the H-shaped building, is a picture of understated elegance, surrounded as it is by an intense weave of bamboo groves, cypresses, osmanthus and Chinese scholar trees, their delicate stems weighed down by the close-knit line of leaves, plunging downwards like a fountain.

Once home to members of the Qing (1644-1911) imperial family, and a guesthouse for distinguished guests from abroad in the early 20th century such as the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore, today, this serves as offices for university staff, working away at their computers without a sound.

The Peking University campus is somewhat livelier, with a steady stream of young people, often dressed in flamboyant jackets and scarves, pouring in through its gates.

Sanjiaodi, the triangular patch lined with convenience stores, hair salons, souvenir shops and some of Beijing's best value eateries about 200 meters south of the grand Peking University Centennial Hall, is like a window on students' opinions.

I saw a series of graphics, documenting the "hard" lives of students - slogging all day, falling asleep in libraries and doing menial jobs on the side to make ends meet.

The anxiety is reflected elsewhere as well. What used to be a sprawling Shaoyuan garden, built by a Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) scholar, has vanished. In its place stands the barrack-like guesthouse named after the garden. More structures are being built, still hidden under green netting and scaffolding. The construction area is barricaded by corrugated sheets that are plastered with adverts of suits for hire when seeking job interviews.

This is not to say all of Peking University's green patches are making way for new architecture. A little north, behind the bronze sculpture of 6th-century Spanish novelist Miguel de Cervantes, are Beida's (as the school is fondly called) picturesque lakes, with small white ornamental marble bridges running across them. The gingko trees stand in regal splendor, radiating light from their golden boughs. Vines work their way up the red brick walls of buildings, designed like English cottages.

The Peking University History Museum provides a good overview of the life and times of this school, founded in 1898. Spread out in five exhibition halls across three floors, the displays throw light on the roles played by some of the earliest thinkers and social reformers who passed through the gates of the university. They include Communist Party of China co-founder Chen Duxiu (1879-1942) and the journalist, ideologue and reformist leader Liang Qichao (1873-1929). Former Microsoft CEO Bill Gates' interaction with Peking University students, well before Gates became a trustee of the school in 2007, is also a feature.

Arguably the most picturesque area of Peking University is around the serene Weiming Lake. The iconic multi-tiered Boya Tower - which borrows its design from Liao architectural traditions but was built in 1924 as a water reserve - is reflected on its placid waters and has a soothing effect on the beholder.

A little red arch on its south bank that's scribbled with messages of love and a short flight of uneven stone slabs lead to a tablet erected in memory of the American journalist Edgar Snow, of Red Star Over China fame.

The west gate of Peking University is known for its ornate beauty and typical Qing-style design. It leads to one of the greenest, most symmetrically laid out areas of the campus, lined by tall coniferous trees.

On either side of the paved walkway stand two ornamental pillars that predate the university by a couple of hundred years. These survived the destruction of the Old Summer Palace in 1860 by French and British troops, when the negotiations over the Opium War seemed to have reached a dead end. At Peking University, the pillars seem to have found the honor and respect that is history's due.