Wired for gold

Updated: 2011-11-16 07:59

By Cheng Anqi and Erik Nilsson (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

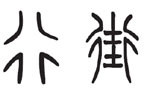

A worker sorts through piles of wasted wires in Guangdong province's Guiyu town, where illegal e-waste processing is the pillar industry. Provided to China Daily |

|

A migrant worker burns computer panels to separate the usable parts in Guiyu. Provided to China Daily |

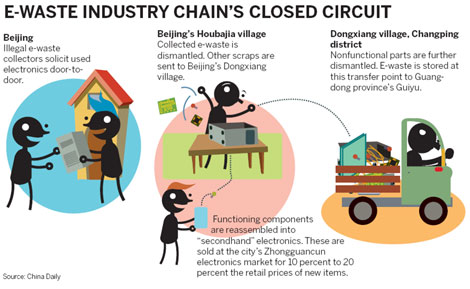

Unlicensed e-waste recyclers in Beijing and migrant workers in Guangdong province's Guiyu town extract gold, silver and other valuable metals from discarded electronic appliances, a business that operates illegally and has significant health risks - but also generates huge profits. Cheng Anqi and Erik Nilsson go undercover to find out more.

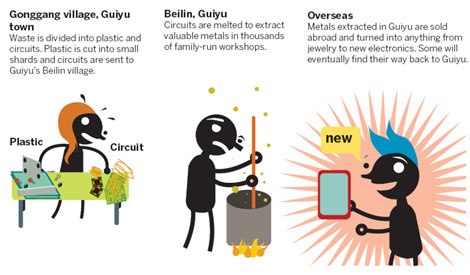

Huang Yan coughs as she deposits a large circuit board in a coal stove. Wisps of toxic smoke curl off the board as it softens, blisters then dribbles. Huang describes her health problems as she melts e-waste - discarded electronics like computers and mobile phones - with 12 other migrant workers in an illegal 20-square-meter family-run workshop in Guangdong province's Guiyu town. "Sometimes," the 32-year-old says, "I cough up blood." Huang tries to elaborate but instead wheezes and smiles mournfully.

She earns 30 yuan ($4.73) a day for nine hours spent extracting small but valuable amounts of gold, silver, copper and other substances from used circuit boards.

The woman believes her chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and kidney stones are caused by the soot and poisons, including sulfur dioxide, that billow out while she fires circuit boards to melt the metals into extractable goop.

Black market e-waste processing is the economic pillar of Guiyu town in Shantou city. The industry employed more than 80 percent of residents three years ago.

But the global economic downturn has exerted gravity on copper prices since 2008, reducing e-waste recycling's profitability and, in turn, the pollution it expels.

However, people like Huang, who moved from Hunan province to Guiyu's Beilin village to find work 19 years ago, remain sick.

"I was told this was a place where jobs were available, and people without higher education could make money," says Huang, who is raising a family of four.

But her health deteriorated as her finances improved.

She started feeling intense back pains and stomachaches that turned out to be kidney stones.

The Yaohui Hospital in Shantou city warned her family against drinking the water when every member developed kidney stones.

The toxic byproducts of e-waste recycling are dumped into the town's waterways, poisoning the groundwater and wells, Shantou University Medical College cytological analysis professor Huo Xia says. Kidney stones are among the ailments they cause. Greenpeace East Asia reports about 30 percent of migrant workers in Guiyu had them in 2009.

Most residents are migrants lured by the e-waste processing opportunities, while many families with local hukou (residency permits) have made fortunes from e-waste and relocated outside because of the pollution. They employ the migrants to run their businesses in their absences.

Huang says her family buys drinking water from the neighboring areas for 2 or 3 yuan (31-47 US cents) per 3 liters.

"But we must use polluted water for washing vegetables and dishes," she says.

People like Huang say they don't want their children to go through what they have.

The 31-year-old Zheng Shouren, from Jiangxi province, has suffered from chronic bronchitis for two of the five years he has worked as a plastic cutter in an e-waste storehouse.

"I cough a lot every day, and there is a lot of phlegm," he yells, above the screech of a saw that throws up rooster tails of acrid smoke.

"Our boss only drives into town on weekends to check on the business and won't stay long."

Chen Demin quit working as a plastic cutter to escape the toxic haze two years ago to wash the cut fragments.

The 28-year-old extends cracked hands for examination. One peeling fingertip bleeds.

He washes the shards in a solution of lime powder or saltwater to separate different toxic yet valuable substances.

"It's too sad to even look at my hands and too painful to straighten them," Chen says.

"I often wear gloves packed with lotion to keep them from hurting. It's like a toothache in my fingers and palms."

Chen and other Guiyu workers are still laboring despite the drop in market prices for the precious metals they extract.

"The recession will pass," Chen says.

"And business will get better when the price picks up. It's just a matter of time."