Modern Silk Road links China, Kazakhstan

Updated: 2011-12-09 08:31

By Cui Jia and Zhao Shengnan (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

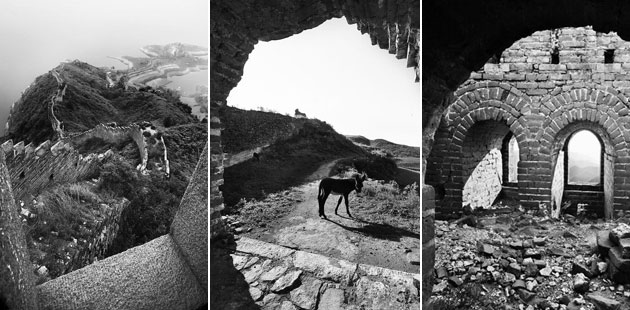

Clockwise from top: People try to squeeze themselves and all their trading goods onto a long-distance bus for a short ride. They are traveling from Horgos port, in China's Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, to the customs checkpoint in Kazakhstan just 10 minutes away. A couple take wedding pictures at the 28 Panfilov Heroes Memorial Park in Almaty. No one leaves the United Asia market empty handed. It is the largest wholesale and retail market in Almaty, and it specializes in products from China. Business is buzzing at Lin Zhenpeng's stationery stall. Azhar Orazgaliev, 86, wears the medals of her World War II years in the Red Army and lives in a house provided by CNPC-AMG and the local government. She is retired from AMG. Passengers while away time at Almaty International Airport. [Photos by Jiang Dong / China Daily] |

Related video: A trip to Kazakhstan

Border trade thrives but visa problems, customs rules are hitting small vendors very hard, Cui Jia and Zhao Shengnan report from Xinjiang and Kazakhstan.

Turson Yeermanhan rushed to the customs office as soon as it opened in a cold winter morning in Horgos, the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region.

Behind him he dragged a trolley loaded with large cardboard boxes filled with baby clothes, toys, vegetables and Christmas decorations.

The 25-year-old is among hundreds of small traders who live on the border between China and Kazakhstan.

Economic relations between the two countries have the advantage of more than proximity. There is mutual benefit in the flow of oil and natural gas from west to east, and of goods from east to west.

The Kazakhstanis "cannot live without us. Almost everything they use comes from China", Turson said.

He is a member of China's Kazak ethnic group, most of whom live in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, which shares a border with Kazakhstan. "We (China Kazaks) have natural advantages, including culture and the languages of doing business with the Kazakhs."

Horgos, in Xinjiang's Ili Kazak autonomous prefecture, once echoed with camel bells as an important passage in Silk Road trade routes. Now, 100 to 300 vehicles carry products - textiles, fruit, daily necessities, mechanical equipment and appliances - to Kazakhstan through the port, the main entry point for imports from China.

In the first six months this year, more than 310,000 people passed through customs and immigration. The volume of imports and exports reached 4.82 million tons, almost triple the total a year earlier.

Turson has been in the business for more than six years and, like many dealers who frequently cross the border, he is well known to both Chinese and Kazakhstani customs officers. That has made his job much easier, he said.

"Sometimes Chinese traders have to bribe Kazakh customs officers. Otherwise they won't let their goods pass," he said. "Asking for bribes is pretty common in Kazakhstan. Sometimes, Chinese are fined for no reason."

As a case in point, Kazakhstani authorities arrested the head of customs at Horgos on April 28. He was suspected of tariff evasion, taking bribes and corruption.

10 jam-packed minutes

Kazakhstan has an abundance of oil and minerals, but with the Soviet Union's breakdown in the early 1990s, it found itself in great need of everyday articles and agricultural goods. That spurred demand for trade with neighboring China, which is equally thirsty for natural resources to fuel its rapid growth.

"Kazakhstan authorities ordered customs to stop operations at Horgos after 2003's SARS epidemic to prevent its people getting infected by people and goods from China," said Yang Jihong, director of Horgos Special Developing Zone Working Committee's information office.

"But they then had no choice but to resume the service after just eight days. The retail price of agricultural products and daily-use products went through the roof."

"The trade between China and Kazakhstan is certainly booming, and there was even a point when China customs couldn't keep up with it," Turson recalled. "In 2007, it took months at customs to declare the summer clothes I was selling. When I finally went through all the procedures, it was winter."

In April, the entry-exit administration office extended its work from eight hours a day to 12 but still cannot meet the flood of travelers, said the office's chief, Ning Xin.

At Horgos, traders with their goods squeeze into every inch of space on the long-distance coach from Urumqi, capital of Xinjiang, to Almaty, former capital of Kazakhstan, so they can ride from one checkpoint to the other. In such close quarters, Turson struggled to turn his head to speak.

"I have a van and a business partner waiting to transport me and the goods to Almaty as soon as I pass Kazakhstan customs," he said. "To be honest, the 10-minute drive between the two customs checks is the part that gives me the most headaches."

As the bus left the white-fenced Chinese territory for the blue-fenced Kazakhstan side, Turson said that he greatly hopes China and Kazakhstan will resurrect the shuttle buses that used to run between the two checkpoints. Service was suspended in 2008 for undisclosed reasons.