Slaves to humor

Updated: 2016-09-16 07:11

By Raymond Zhou(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||

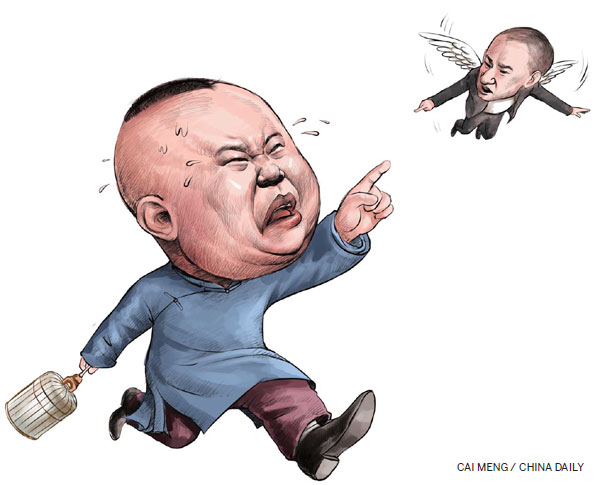

Fracas involving a comedy master and his former student has put a spotlight on China's outdated apprenticeship system, which is not the best way to train budding talent

In 2010, Guo Degang and Cao Yunjin had a falling out. It took them six years to air the dirty laundry in public.

Both Guo and Cao are comedians specializing in the genre of cross-talk, or xiangsheng, which is the Chinese equivalent of stand-up comedy.

In 2002, Cao (born in 1986) became the apprentice of Guo (born in 1973). In recent weeks, Guo publicized a formal "family tree", in which generations of apprentices are listed. A footnote specifies that two members with the word yun in their names have been expelled and Cao is one of them.

Guo requested Cao remove yun from his stage name but the latter declined. Instead, Cao published a long article detailing all the "wrongs" Master Guo had done to him, causing him to leave six years ago.

While Cao's accusations have not been corroborated, it is clear that his departure was not easy on his former boss, who considers it a betrayal and has all along railed against him in public, albeit without naming names.

It is premature for an outsider like me to conclude who is in the right, but what is certain is that the apprenticeship tradition practiced in China for hundreds of years is seriously out of touch with reality.

When I was very little I heard that teenage boys would be given to "masters" to acquire certain skills, such as carpentry or masonry. Usually, the parents of the child were so poor that they could not afford to pay tuition for a regular school and would have one fewer mouth to feed, with the child fed and clothed by the master's family.

A good master would have so many children sent to him that he would send the incompetent away. The capable ones would "graduate" and work for him down the road.

Now that I think of it, it was indeed a variation of indentured servitude, but both sides entered the arrangement knowing full well what it entailed - that is, the master would teach for free, plus provide food and lodging, and the apprentice would work for him without pay, at least for a certain length of time. Three years in the cross-talk world, it is said.

Of course there are differences from place to place and from vocation to vocation. In the 2016 film Song of the Phoenix, the children carried their own food when they were sent to stay with their master to learn a traditional musical instrument, the suona. That was a story set in the 1980s.

A lot of Chinese movies would portray masters as symbols of tough love and their wives as gentle and kind. In not a single case has there been sexual abuse from the master. But the Peking Opera school in the classic film Farewell My Concubine was deemed by Western critics as "worse than the orphanage in a Dickens novel".

Cao did not view himself as an apprentice who sold himself into servitude, partly because he paid tuition to Guo. He stayed in Guo's home, doing household chores for three years. But he said he had no complaints. His frictions with his master began when the latter dictated career choices that he deemed unfavorable for his growth.

When Cao was given a 18-minute solo slot by China Central TV, seen by many as a rare chance for a breakthrough, he was ordered by Guo to quit, who was not on friendly terms with the all-powerful television station back then.

Guo may call his comedy school/club Deyun Society, but it is by all means a business. When he himself was down and out, it was easy for his employees to accept little or no pay. After all, whatever percentage of earnings one gets from zero is still zero. But when he started to rake in big bucks, his feudal style of income distribution would soon run into the wall.

Because his master-apprentice system does not leave room for a mutually respectful form of employee departure, it is only natural that the most talented ones would not stay with him for long.

Guo is just like one of those business founders who take it personally when lieutenants or underlings he trusts find greener pastures. They did not threaten his survival because, unlike similar situations in high-tech, the market for comedy is big enough to accommodate dozens of such organizations and hundreds of such entertainers.

Rather, their departures are subversive to the old, hierarchical mode of education and business operation, to which Guo subscribes. If followed to the letter, the Chinese system demands that the apprentice obeys the master no matter what.

However, Guo might have forgotten that he was not loyal to this system either: He jumped from one master to another, a big no-no as an apprentice, and he bad-mouthed predecessors like Jiang Kun. In a sense, he whipped up a storm in the world of cross-talk partly because he was not a docile follower and was ready to break rules. But he would not accept his charges acting the same way.

China has two major comedy clans (the other led by Zhao Benshan) but no comedy schools. The art of comedy is imparted through this kind of ritual-ridden and humorless apparatus. Why can't Guo open a modern school of comedy and charge reasonable fees for his services? He may end up making more money as a founder of a modern school, which, like a modern enterprise, is able to scale up its business.

I have always wondered why Chinese schools do not teach comedy. Yes, genius cannot be taught, but craftsmanship can. Out of many run-of-the-mill comedy students will be virtuosos who build their own styles. They do not have to learn from a single master, but from all the good ones in the whole world.

The illusion that a teacher "owns" a student is primordial. The old saying "A teacher for a day, a father for a lifetime" should not be taken literally - not in most cases. Even a father should give his children independence once they grow up.

Yes, we are all touched by those tales of student-teacher relationships elevated to those of surrogate fathers and children, but those are the exceptions.

As for the word yun in his stage name, it is tantamount to branding for Guo's organization. So, Cao should give it up since he is no longer a member.

Contact the writer at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 09/16/2016 page22)

Today's Top News

UK gives Hinkley Point nuclear power green light

Hillary Clinton remains healthy: doctor

UK confirms Hinkley project with 'new agreement'

Despite big deals, data shows less M&As after Brexit

New plan for grammar schools welcomed by Chinese

Moscow denies involvement in hacker attacks on WADA

EU should stay strong, stable and united: Tusk

Cameron to quit as MP; by-election triggered

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|