New plan for grammar schools welcomed by Chinese

Updated: 2016-09-14 16:59

By WANG MINGJIE(China Daily UK)

|

|||||||||

Chinese communities in the UK have welcomed Prime Minister Theresa May's new grammar schools plan, which aims to attract pupils from various backgrounds and make Britain "the great meritocracy of the world."

The new schools will be encouraged to recruit students at age 14 and 16 as well as 11 to boost social mobility and help children from disadvantaged backgrounds avoid being written off as "non-academic".

Alex Yip, vice-chairman of The British Chinese Project, an organization that promotes engagement between the Chinese community and UK society, says the new proposals will give pupils a fair chance to go as far as their talent and hard work allow.

He added, "How can this not be welcomed by aspiring and hardworking Chinese families across the country?"

Grammar schools are state-funded, but draw their pupils through a national test, originally known as the 11-plus.

Critics say the system is elitist and when government control of education devolved to local authorities in the late 1960s many grammar schools became comprehensives, admitting pupils of all abilities without them taking an entrance exam.

Jackson Ng, director of Conservative Friends of the Chinese, believes Britain should be a place where advantage is based on individual merit not privilege, where talent and hard work matter, not one's place of birth, background, or even accent.

Jenny Wong, director of Manchester Chinese Centre, said, "Our Chinese parents are very keen about Theresa May's grammar school plan, and we were talking about it last weekend."

Chinese children are among the highest academic achievers in the UK. Recent government statistics show the odds of achieving five or more A*-C grades in the General Certificate of Secondary Education are about twice as high for Chinese pupils than for British ones.

Pupils typically sit the GCSE when they are either 15 or 16, and then A-levels two years later, which are assessed when a student applies to a university.

Wang said Chinese parents like to invest heavily in their children's futures and schooling is their first investment.

In England, there are 163 grammar schools, but more than two-thirds of the 150 local authorities have none of these schools. Areas that do have them tend to be in the more affluent parts of southern England.

Wong said the government should build more grammar schools in deprived areas, as pupils from deprived social backgrounds are often at an educational disadvantage.

"Children in these areas lack opportunity and parental support, and therefore a good grammar school could change the lifestyle of a young child," Wong added.

Since May announced the grammar school plan, some politicians have argued that selection on merit would be replaced by selection on financial grounds, because middle-class parents could pay for intensive tutoring for the 11-plus.

Sun Lulu, a lecturer at Nankai University and a Doctor of Philosophy in education studies at the Institute of Education, University College London, said that for Chinese families in the UK, the increasing number of grammar schools will widen parents' choices for their children.

"The success or failure system of grammar school entry is not a measurement to split children into winners and losers," Sun said.

"Grammar school doesn't disadvantage those children who don't get in. In this case, more care is needed to choose the best schools for children. It is also important to remember that the education that suits a child is the best."

Related Stories

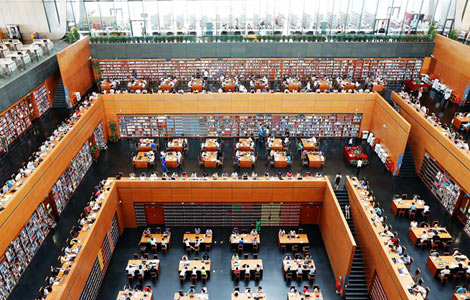

UK students get chance to learn the Chinese way 2016-09-12 18:00

UK students begin second China journey 2014-04-23 16:33

Today's Top News

China vows aid to resolve refugee crises

New York bombing suspect captured in New Jersey

United Russia party leads in parliamentary elections

Bomb suspect in custody in New Jersey: media reports

Oktoberfest parade held in Munich

New York to deploy 'bigger than ever' police presence

UK's anti-EU party elects new leader as Farage quits

Trump concedes Obama was born in US

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|