No reason for angst on China's GDP

Updated: 2016-01-01 08:19

By Cecily Liu(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

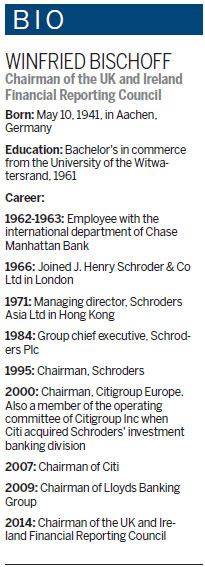

Former chairman of Lloyds Banking Group says even 6 percent growth would present few concerns

Winfried Bischoff has no concerns about China's slowing economic growth. He's done the math.

According to the former Lloyd's Banking Group chairman, recording a growth rate of just 6 percent this year would be the equivalent of recording 10 percent in 2008.

|

Winfried Bischoff says China will continue to do well in actual growth terms despite lower growth rates. Cecily Liu / China Daily |

"Who would have worried about 10 percent in 2008?" he asks.

Bischoff says his calculation is based on figures from a recent Standard & Poor's research article on China's contribution to global economic growth in 2014.

"People worry about China, but I don't worry," he says. "China will continue to do well in growth terms, although less in percentage terms. China is catching up with the United States, and we think 3 to 4 percent growth is fantastic for the US, so we have to get real about China's growth rate.

"China's greatest contribution to the world is to keep doing what it has been doing, which is to grow consumption."

In fact, he believes the country's ongoing contribution to global growth - in Asia, in particular - could have the same effect as when the United States launched its Marshall Plan in the late 1940s.

The plan, officially the European Recovery Program, saw the US give $13 billion - equal to about $90 billion in today's money - to help rebuild Western Europe after World War II. As a result, as these nations recovered their citizens were more able to buy American products.

"You cannot become rich on your own because unless your neighbors become rich you can't sell," Bischoff says. "The Marshall Plan helped Europe - with credit and loans. The US economy needed countries to be able to absorb the substantial production of which it was capable.

"My analogy is that, in order for China to continue to prosper, it may need to help some of its customer countries in two ways: Credit or, more directly, buying these countries' goods or raw materials. Growth in the domestic economy should enable both of these actions."

Bischoff, now chairman of the UK and Ireland Financial Reporting Council, an independent regulator aimed at fostering investment, has had a long career in London's financial services industry. Before taking the helm at Lloyds in 2009, he held top positions with Citigroup and Schroders.

Over his career, he has witnessed firsthand the rapid rise of China, which has increasingly become integrated in the global economy through its investments and the internationalization of its currency, the renminbi.

"There is a lot of currency, trade and investment flow into and from China," he says. "There is willingness among many global companies to start operations in China, and more Chinese companies have been going global, especially in the past three to four years. It's positive because the two-way trade is not just in goods."

In November, the International Monetary Fund decided to include the renminbi in its special drawing rights basket, which was hailed as a milestone in China's efforts to make the renminbi a major global reserve currency.

For Bischoff, the decision was significant because he feels it gives the renminbi an international status that reflects China's economic strength, and will help China's integration into the world financial systems. "The People's Bank of China (the central bank) has a great desire to make the renminbi a reserve currency, and it reflects China's economic strength and outward vision."

Chinese explorer Zheng He's expedition to Africa in the 15th century is an example of the country's outward-looking mind-set, he says, but since then China has largely focused inward. That is changing, though, as the economy becomes more international, he adds.

China has been seeking to rebalance its economy in recent years, moving away from relying on exports-driven manufacturing to high-value-added service sectors and domestic consumption.

To ensure the transition is successful, Bischoff says maintaining social cohesion is the most important element when it comes to preventing China from falling into the so-called middle-income trap. "In the countryside and the cities, there are skilled workers and not-so-skilled workers. They need to be in harmony."

Bischoff first visited China in 1973, stopping off in the cities of Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin and Guangzhou, as well as Shandong province. He remembers the country as "very primitive" back then, and says it has since changed beyond recognition.

"For example, (one morning) we were given fried eggs for breakfast," he recalls. "Our hosts had made them the night before and put them in the fridge. They wanted to please us, but ice-cold fried eggs are not very nice. Nowadays, in Chinese hotels, you can get the most wonderful Western or Chinese food. (The country) has opened up."

Born in Aachen, western Germany, in 1941, Bischoff was educated in Cologne and Dusseldorf before graduating from Johannesburg's University of Witwatersrand in 1961 with a degree in commerce.

He started his career in the international department of Chase Manhattan Bank and, in 1966, joined the British asset management company J. Henry Schroder & Co. It was this job that led him to Asia.

He says he was asked to go to Hong Kong to launch the company's merchant banking division, and at first he was hesitant. "I said I didn't want to do that because I was traveling every second week to the US for my law school studies."

What changed his mind was a book, The Year 2000 by Kahn Herman and Anthony J. Wiener, published in 1968, which he received from a colleague. Kahn founded the Hudson Institute and was one of the preeminent futurists of the latter part of the 20th century.

"The book put forward the idea that Japan would grow so fast that it will overtake the US in per capita GDP, and that the centrifugal effect Japan will have on other countries like Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore would be significant. I got to page 65 and then agreed to go (to Asia). It was the right thing to do."

Looking back, Bischoff says Hong Kong was the "greatest place" for people of his generation. He enjoyed exploring Asia during those years, as he found it to be diverse in terms of ethnicity, religion and geography.

He eventually became managing director of Schroders Asia Ltd, based in Hong Kong, and was later appointed group chief executive of Schroders Plc in 1984 and then chairman in 1995.

He credits Hong Kong with playing an important role in his career and believes the city and the Chinese mainland are irrevocably linked.

"I've been to China many times, and I think Hong Kong would not (be so important) if it were not useful to the mainland," he says. "The Hong Kong economy grew substantially between 1970 and 1982, but not in a straight, uninterrupted line. That resulted - in 1973 and 1974, for example - in periods of no growth.

"The experience of growing a business during ups and downs stood me in good stead later in life."

cecily.liu@mail.chinadailyuk.com

( China Daily European Weekly 01/01/2016 page32)

Today's Top News

Storm Frank batters northern Britain

Over 1 million refugees fled to Europe by sea in 2015

Germany to spend 17b euros on refugees in 2016

Demand booms for high-end financial talent

Abe expresses apology for Korean victims of comfort women

North China encounters gas supply shortage

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank launched

Russia says it has proof of Turkey's support for IS

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|