Lessons from a prince on mergers and acquisitions

Updated: 2011-12-02 15:52

By Maurice Hoo (China Daily European Weekly)

|

|||||||||

In a field fraught with dangers, the golden rule applies: caveat emptor

Before the Manchurians moved into Beijing and established the Qing Dynasty in 1644, the Manchu prince Dorgon spent several decades in what is now Shenyang to study the Han-controlled Ming empire - its history, government, language, values, systems, and even court customs and personalities - to prepare, one day, to rule the Han majority. With this thorough homework, the Manchurians became the most successful ethnic rulers in Chinese history; the Qing Dynasty lasted for more than 260 years, while the Mongolian-controlled Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) lasted only 97 years.

In late 2008 and early 2009 various companies in developed economies that were hard hit by the global financial crisis, such as the US and Western Europe, that were looking for capital to expand or just survive, asked me if my Chinese corporate or financial investor clients would be interested in their companies as acquisition or investment targets. I told them the story of Prince Dorgon.

According to statistics issued by the Ministry of Commerce last year, the Chinese mainland made $68.8 billion of outbound direct investment, becoming the world's fifth largest outbound investor after the US, Germany, France and Hong Kong. Given the fact that a large portion of the outbound investments accredited to Hong Kong actually flowed from the mainland, the Chinese mainland's real ranking could be even higher. Ministry of Commerce statistics also showed that China's volume of overseas mergers and acquisitions grew 54.7 percent to $29.7 billion over the year, accounting for 43.2 percent of China's total overseas direct investment.

|

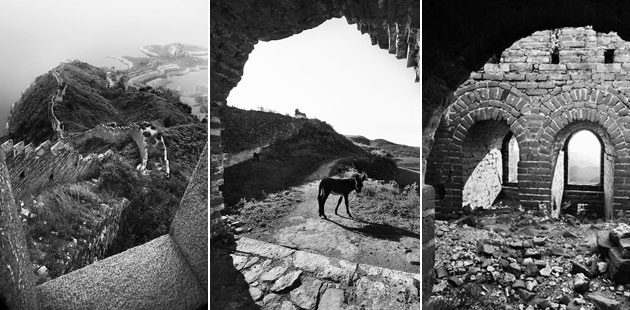

Zhang Chengliang / China Daily |

Mergers and acquisitions have become an important form of China's overseas direct investment. While the motives of investors and acquirers can be as many and varied as the number of outfits involved, the following are among the main reasons for Chinese companies' cross-border mergers and acquisitions:

Natural resources: Whether to continue to fuel manufacturing for export or internal consumption, or to keep the massive urbanization project on track, Chinese companies in the energy (including oil, coal, and natural gas) and raw materials (such as various metals) sectors (government controlled or not) are constantly looking for stable and reasonably priced supplies, whether through long-term contracts, joint ventures or acquisitions.

Technology: The Chinese government has made great efforts in recent years to encourage Chinese companies to "move up the industry chain" from the low-end, low-profit-margin, labor-intensive and energy-intensive industries, to those high-margin, environmentally friendly and "knowledge-intensive" industries, and many Chinese companies are taking that encouragement on board. Chinese technology firms are looking to acquire technologies to help them upgrade products and processes, reinforce market share and reduce intellectual property lawsuits from foreign competitors. Huawei's abortive acquisitions of 3Com and intellectual properties from 3Leaf are examples of this type of acquisition. (Both ultimately failed when the US Committee on Foreign Investment blocked the deals).

Brand: Chinese companies' purposes to buy foreign brands are diverse. Some have a global view and hope to break into the international market with an established brand. For example, Geely probably would have remained unknown outside China if it had not bought Volvo. Others aim to strengthen their brands in the Chinese market by controlling a strong foreign brand. For example, in 2009 a company registered in Wenzhou, a city in Zhejiang province renowned for its light manufacturing, acquired the right to use the Pierre Cardin brand in China.

Networks outside China: Foreign companies' sales, distribution, service and support networks in their host countries have become an obvious attraction for Chinese investors only recently. However, in the past four years ICBC bought a 20 percent interest in a leading South African bank, China Merchants Bank bought Wing Lung Bank in Hong Kong, and the Chinese retail giant Suning became the biggest shareholder of LAOX, the second largest electronics retailer in Japan. By buying into the local networks, the acquirers could serve their Chinese customers or clients overseas with local presence and at the same time sell their products or services in the new markets.

Often a Chinese acquirer or investor has a combination of motives. For example, Lenovo acquired technologies, brand, local networks and production capacity at the same time by buying IBM's personal computer business.

Unfortunately, flushed with cash, more and more Chinese companies and investors these days are tempted to jump before they look when it comes to foreign acquisitions, not appreciating that they can not only lose their investments, but incur other losses and harm to themselves beyond that. As I have advised many clients, knowing your desired destination is more important than knowing how to get there. Mergers and acquisitions may or may not be the most effective, or the least expensive, or the least risky, option.

Overseas mergers and acquisitions are challenging because they involve taking over a different business from a different culture under a different legal and tax regime and different industry practice. The Chinese acquirer or investor must carefully consider not only the risk of being unable to close the deal but the risk of being unable to run the business after closing the deal.

Cross-border mergers and acquisitions are heavily regulated in many jurisdictions and are usually subject to stringent governmental scrutiny. This issue becomes more complicated when the acquirer is a Chinese State-owned enterprise. (In 2005, the US Committee on Foreign Investment blocked CNOOC's proposed acquisition of the US oil company Unocal. Then, in 2009, the collapse of Chinalco's proposed acquisition of Rio Tinto was widely believed to be attributable to political pressures despite the Australian government's denials. Beyond national security or political considerations, there can be anti-trust, capital markets (if either the acquirer or the target is a public company), financing and other challenges. Many of these potential acquirers not only incurred substantial out-of-pocket expenses and used valuable internal resources on these failed attempts, but had to deal with negative international publicity and poor internal morale in the aftermath.

Even if the acquisition successfully closes, the real challenges are only about to begin - how to successfully run (and perhaps integrate) a foreign company. As an example, in 2004 Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporate (SAIC) announced its acquisition of SsangYong, a major automobile manufacturer in South Korea. The financial crisis came soon after an unsuccessful attempt by SAIC to market the SsangYong brand in the Chinese market. SsangYong's labor union rejected any lay-off plan SAIC put forward to cope with the market downturn. After years of strikes and even personal conflicts between the Chinese management and the South Korean workers, SAIC reaped only huge losses (reportedly billions of renminbi) as SsangYong entered into reorganization in 2009.

In addition to labor issues, an acquirer can get caught in intellectual property, environment, land, tax, government reporting and other issues in foreign jurisdictions, as well as existing disputes or even lawsuits between the target and other third parties. For example, if a Chinese company acquires a company in California without ticking the appropriate boxes with the California Franchise Tax Board, the Chinese parent may be required to report the worldwide income of the entire corporate group to California - in other words, some of these risks go beyond the acquired entity or business and can "infect" the parent.

Such risks should not be dismissed or understated as "operational risks" to be dealt with after the investment or acquisition closes. They need to be studied and their solutions or management considered before it is decided to invest or to buy. SAIC's misfortune should remind every Chinese company to resist any temptation to make trophy acquisitions, or to make investments only because it is possible to do so.

Cross-border acquisitions can be a worthy undertaking for some, but the acquirer needs to focus on its objectives, be vigilant for risks, and obtain competent and loyal advice, before proceeding. We can all learn from Prince Dorgon how he prepared for his acquisition.

The author is one of the Global Co-Heads of Private Equity at Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP. The views expressed in the article do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.