Rural families still hope for male heirs

Updated: 2015-09-05 07:47

By Andrew Moody(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

Oxford professor says 'Care for Girls' has had some success in stamping out selective abortions

|

Rachel Murphy is writing her second book on the phenomenon of so-called left-behind children in rural areas. Nick J.B. Moore / For China Daily |

Rachel Murphy says the preference for couples to have sons in rural China still remains very strong.

The associate professor of sociology at Oxford University says having a boy in a society where there is not much social welfare provision is the only way to ensure future financial security.

"I remember talking to a woman who said her life was not going well because she had given birth to another daughter," she says.

"I told here not to be too despondent because President Obama has two daughters. She just said, 'Yes, but he is not a Chinese farmer.'"

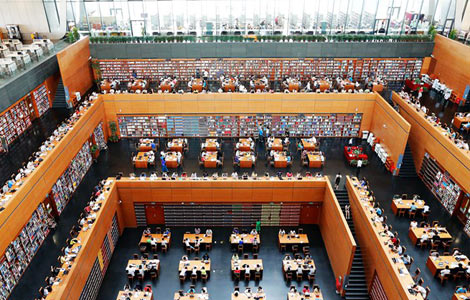

Murphy, a 44-year-old Australian, was speaking in the new Dickson Poon China Centre at Oxford University.

She has spent much of her career studying rural people in China, particularly in Jiangxi and Anhui provinces.

One of her specialties is China's sex-ratio imbalances. After the family planning policy was introduced in 1979, the number of boys born for every 100 girls soared to 120 in 2000 (more than 130 in some rural areas), boosted partly when ultrasound technology made abortion of female foetuses possible. The government aims to bring the ratio down to 112 next year. The natural birth rate where there is no family planning policy is 105 boys to girls across all societies.

"This imbalance was there historically and all through the Mao period as well. Chinese parents have always wanted to have at least one son and just carried on having children until they had a son."

Murphy believes the Chinese government has had some success in righting the imbalance with its Care for Girls, a program first piloted in 2003 and aimed at stamping out selective abortion.

She believes there might be special cultural factors in China that make it difficult to eradicate preference for sons altogether.

"There was a view that China would become like South Korea. It, too, had this sex-ratio imbalance, but as the country urbanized this was largely eradicated.

"In China, both rich and poor areas have sex-ratio imbalances, however. This is particularly the case among wealthy entrepreneurs who want to pass on their property to their sons."

Murphy, who was brought up in Perth, Western Australia, only started to learn Chinese at school because it clashed with the timetable for sports - something she dreaded. "In Australia, it is fairly miserable to be a child who is no good at sport, but I did enjoy Chinese very much and studied it from the age of 12."

When she was 17, she was one of eight Australians selected for the Australian Young Scholars Study Year in China program, through which she attended both Beijing Second Foreign Languages Institute and East China Normal University in Shanghai.

"It was the first time any of us had spent any time living away from home and it was a great adventure. I remember seeing so many rural people at Beijing Railway Station with their mesh sacks wondering where they had come from and what they were doing."

She went on to get a double major degree in Asian and cultural studies at Murdoch University in Perth before moving to the UK to do a PhD in sociology at Cambridge University.

Murphy then pursued an academic career, taking in academic posts at Cambridge and Bristol universities before moving to Oxford in 2007.

She has since headed the Asian Studies Centre and from the beginning of this year was made head of the School of Interdisciplinary Area Studies. She is widely regarded as one of Europe's leading experts on the sociology of China.

Her first book, How Migrant Labor is Changing Rural China, published in both English and Chinese, sold 5,000 copies, which is considered high for an academic work.

Before starting a family of her own, Murphy had spent three or four months every other year doing field work. This involved staying in county or township government state houses and interviewing children and families.

"It is what I call deep hanging out. When I was doing my PhD, I had officials accompanying me at the beginning. I was asking family after family the same questions and they soon got bored," she says laughing.

Today's Top News

Austria to end messures letting migrants in

Ex-VP nominee Palin: Immigrants in US should 'speak American'

China 2014 GDP growth revised down to 7.3%

Acquiring knowledge, building strength

Foreign bears don't affect China - yet

White paper on Tibet reaffirms living Buddha policy

Austria, Germany open borders to migrants

PBOC governor says stock market correction roughly in place

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|