'One suicide is too many'

Updated: 2012-07-24 09:07

By Yang Yijun and Xu Junqian (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

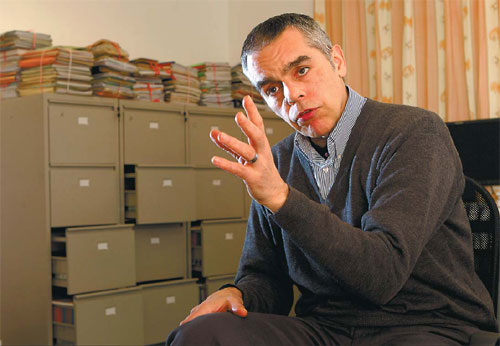

The Canadian Michael Phillips is one of the leading experts on suicide in China. Gao Er'Qiang / China Daily |

My China Dream | Michael Phillips

A Canadian psychiatrist pioneers research on people who attempt to kill themselves. Yang Yijun and Xu Junqian report in Shanghai.

Michael Phillips is used to people referring to him as the "modern Henry Norman Bethune" - a reference to the Canadian physician devoted to Chinese people during wartime in the 1930s. The 62-year-old, who's among the leading experts on suicide in China, disagrees. While both are Canadian, Phillips says there's a huge difference between a surgeon and a psychiatrist. And "there's no way Mao Zedong would write an article about me" like he did about Bethune, Phillips says, jokingly.

Phillips, who has pioneered research on Chinese suicide for more than two decades, is also the director of the Suicide Research and Prevention Center of the Shanghai Mental Health Center.

He's leading six scientists to continue his suicide studies in the center's branch in Shanghai's suburban Minhang district.

Phillips first came to China in 1976, when he was working as a doctor in a hospital affiliated to a New Zealand university. He accompanied a student group on a three-week trip.

"It was a very poor country, but still, even in the distant rural areas, there was some level of healthcare, which was not true in India or other countries of similar economic levels at the time," he recalls.

"The thought in the back of my mind was that maybe there was something I could learn here about the public health system. Then, I could promote such a system in other third-world countries like those in Africa."

Two months later, he secured a chance to stay in China for two years as a New Zealand exchange scholar.

But he was not able to attend a school of public health because he was not from a developing country. He used the two years to study Chinese.

"Over those two years, it became clear there were things I could do in China," Phillips says. "But I needed more professional training to make a contribution."

So, he went to the United States to train as a psychiatrist and earned master's degrees in epidemiology and anthropology.

In 1985, he returned to China for good. He has worked in many cities, including Hunan province's capital Changsha, Hubei province's Shashi, Beijing and Shanghai.

Psychiatry was then barely known by the public and the least respected major in the medical field, Phillips says.

He recalls one of his Chinese colleagues dared not tell others he was treating mental health patients.

"If he did, he wouldn't be able to find someone who would be willing to marry him," Phillips says. "At that time, people regarded those working with mental patients at risk of getting a mental illness themselves."

But that wasn't a problem for Phillips, who was already married. His wife, whom he knew during his years in the US, works as a nurse treating mental health patients.

Phillips always had a keen interest in psychiatry and especially in people experiencing psychological crises. The Canadian says he realized this in college, when he was an intern in a hospital emergency room where Phillips occasionally encountered patients who attempted suicide. He would care for them and listen to them after they regained consciousness.

Speaking out

"I came to realize that I really hoped to understand why they wanted to end their own lives," he recalls. "What kind of difficulties had they faced? In fact, it was helpful to simply give them a chance to speak out. I was only 18 or 19 then. But I have subsequently developed an interest in psychiatry and suicide."

China's underdevelopment in the field of psychiatry reinforced Phillips' decision to come.

"I've been able to make contributions here that I probably wouldn't be able to make in the West," he says. That's because the field was relatively under-developed in China, while many were already working in it in the West.

But it took several years before Phillips could touch on the topic of suicide - once a taboo in the field of research, not to mention among the public - in the country.

The chilly attitude started to thaw in 1990, when the Ministry of Health began to provide data on suicide to the World Health Organization.

"It's a huge issue, which was almost blank in China," Phillips says.

"As an interested mental health professional with training in anthropology and epidemiology I was a perfect candidate to take up research on the issue."

He moved to Beijing and cooperated with the country's Center for Disease Control and Prevention to conduct the largest-ever study of suicide in the world. They talked with families to find out the reasons for members' suicides at 23 sites nationwide from 1995-2000.

When the survey was drawing to its end in 1999, Phillips was awarded the Great Wall Friendship Medal, the highest award granted by the Beijing Municipality for "foreign experts who have made outstanding contributions to the country's economic and social progress".

Three years later, Phillips published a paper Suicide Rates in China, 1995-99 in The Lancet, revealing to the international public for the first time a clear picture of China's suicides.

It turns out there are major difference between China and the West when it comes to suicide.

The major difference is that, in the West, 95 percent of people who die of suicide and who attempt suicide have mental illnesses but in China, a third of people who die from suicide and two-thirds who attempt it don't have mental illnesses at the time, Phillips says.

"There is probably more impulsiveness," he explains. "In China, a lot of people don't really want to die but use very lethal means when they attempt suicide, especially pesticides; this is another big difference from the West."

Based on his study, he set out to find ways to save at-risk people.

"One suicide is too many," he says.

That's the slogan his research team developed for the Beijing Suicide Research and Prevention Center, the first of its kind in the country. It was established in 2002 by Beijing Huilongguan Hospital. In 2006, the center became the WHO Collaborating Center in Research and Training in Suicide Prevention.

Phillips was the center's first executive director. It opened the country's first national suicide intervention hotline in 2002.

"Anybody can become suicidal if they have enough stress," Phillips says. "If you have a good social support network, people whom you're able to talk to about difficult things will help you increase your ability to deal with external stress."

But he reiterates that psychiatry alone won't prevent suicides.

"Suicide is a very complicated problem," Phillips says.

He explains that 58 percent of suicides in China are by pesticide ingestion.

"So, we have to restrict access to pesticides," Phillips believes. "That needs cooperation from the Ministry of Agriculture. We also need to have the schools, the police, the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Social Welfare involved. That's something (for which) you need an overall plan that ensures all these different people are working together and the resources are properly allocated - and that's supported by the government, both financially and politically."

Scientific approach

Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention researcher Yang Gonghuan says: "Phillips is the first to combine clinical psychiatry and public health in China. The combination has allowed us to create scientific methods to approach suicide research."

Phillips conquers the stress of dealing with suicide every day by viewing his two daughters' paintings, which show sunshine, green grass and cute girls.

His wife, Marlys Bueber, says Phillips is a "great father". "Though he works very hard, he is always present at our important occasions," she says.

"There's a big influence from him on the two girls. It may be just an assumption, but there's a good chance our bigger daughter chose her science major because of her father."

Both children, ages 19 and 16, speak perfect Mandarin, including to each other, since they were raised in China.

Bueber says it has been interesting living as a family in various Chinese cities over the years.

"We first came here when the country just started its opening-up," she says. "In Shashi, the place we first stayed at in Central China, it was quite difficult to buy an air ticket or to make phone calls back home. China has been changing so rapidly in the past decades and it's been exciting to be part of all the changes."

Phillips has no plans to leave.

"As I age I hope to continue what I've been doing," he says. "I can't think of anything else more interesting to do."

Contact the writers at xujunqian@chinadaily.com.cn.

Related Stories

First China-DPRK movie to be screened in August 2012-07-23 18:12

Georges Braque's Works to Be Shown in China 2012-07-23 17:53

Dama festival kicks off in Gyangze, China's Tibet 2012-07-23 11:05

China bans sales of mud snails 2012-07-23 09:58

Misty scenery around Luodian, China's Guizhou 2012-07-23 09:54

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|