When artifacts become untouchable

Updated: 2012-07-23 11:17

By Ralph Blumenthal and Tom Mashberg (The New York Times)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

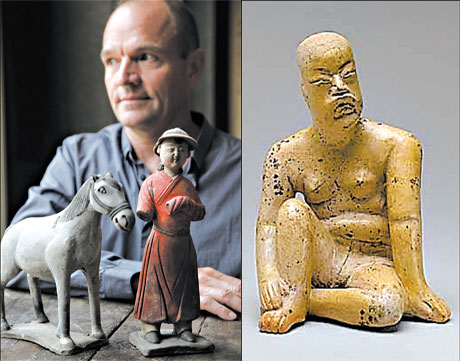

Museums are tightening rules for accepting artifacts. David Dewey with Yuan dynasty items; Allen Brisson-Smith for The New York Times; right, an Olmec-era statue at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Metropolitan museum of art |

|

|

Museums are tightening rules for accepting artifacts. David Dewey with Yuan dynasty items; Allen Brisson-Smith for The New York Times; right, an Olmec-era statue at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Metropolitan museum of art |

More museums require a documented history of items

In the three decades since David Dewey of Minneapolis began collecting Chinese antiquities he has donated dozens to favored museums, enriching the Institute of Arts in his hometown as well as Middlebury College in Vermont, where he studied Mandarin.

But his giving days are largely over, he said, pre-empted by guidelines that most museums now follow on what they accept.

"They just won't take them - can't take them," he said.

Alan M. Dershowitz, the Harvard University law professor, is in a similar bind. An antiquities collector, he is eager to sell an Egyptian sarcophagus he bought from Sotheby's in the early 1990s. But he is stymied, he said, because auction houses are applying tighter policies to the items they accept for consignment.

"I can't get proof of when it came out of Egypt," Mr. Dershowitz said.

Across the United States measures taken to curb the trade in looted artifacts are making it more difficult for collectors to donate, or sell, cultural treasures.

Museums typically no longer want artifacts that lack a documented history stretching back past 1970, a date set by the Association of Art Museum Directors.

Written in 2008, the rules have been applauded by countries seeking to recover artifacts and by archaeologists looking to study objects in their natural settings.

But the sweeping shift in attitudes has left collectors stuck with items they say they purchased in good faith many years ago from reputable dealers. Collectors and their advocates predict museums, cultural scholarship and the items themselves will suffer as important gifts are disallowed. Kate Fitz Gibbon, a lawyer with the Cultural Policy Research Institute, based in Santa Fe, New Mexico, warned that "if we continue on this path, there may not be a next generation of collectors, donors and patrons of ancient art, not in the United States of America anyway."

Others view Ms. Fitz Gibbon's perspective as hyperbolic.

"Antiquities collecting destroys far more than it saves," said Ricardo J. Elia, an archaeology professor at Boston University who specializes in the global art market. "Looting is driven by the art market, by supply and demand."

For centuries collectors have helped define artistic taste and have been the backbone of museums. But the antiquities trade begins, at its source, with an act of appropriation: the removal of artifacts from a native site to one where, in the case of museums, they can be more accessible to scholars and the public.

"Collectors know that without provenance it is impossible to know whether an object was first acquired by illegal or destructive means," said Neil J. Brodie, an archaeologist and former director of the Illicit Antiquities Research Centre at the University of Cambridge.

Momentum for stricter guidelines accelerated several years ago in the aftermath of major acquisition scandals at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and other institutions that ultimately led to the new policies. They strongly discourage museums from buying or accepting objects that cannot pass the 1970 test or lack an export permit from the country of origin.

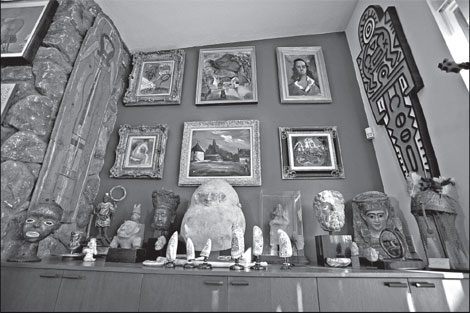

Several years ago the Cultural Policy Research Institute estimated that as many as 111,900 ancient objects from Greek, Roman, Etruscan and related cultures are in private American hands and "unprovenanced."

Arthur A. Houghton III, president of the institute, said that if rejected by museums, these "orphaned" items are likely to end up in private hands outside the country.

But Professor Elia dismisses talk of "orphaning" as patronizing "mythology."

"It ignores the fact that dealing and collecting are causing looting in the first place," he said. "For every object 'rescued' by looters, dealers and collectors, there is a trail of destroyed sites, lost knowledge, broken artifacts and broken laws."

Collectors are uneasy. They worry that placing undocumented items for auction exposes them to litigation from foreign nations or perhaps a seizure effort from United States authorities acting as their agent.

Mr. Houghton suggests creating an amnesty of sorts for collectors who post facts and photos about potentially contested artifacts on a "credible and neutral" database. If the item is not claimed after some number of years, he said, its ownership could no longer be contested.

Mr. Dershowitz said he is not distraught about his inability to sell the wooden Egyptian sarcophagus he purchased from Sotheby's. For now it's in limbo.

Meanwhile, he said, he had another Egyptian sarcophagus at home that he isn't even trying to sell. "I'm keeping that in the house," he said, "in the hall."

The New York Times

Related Stories

Collection of Chinese Antiques 2012-07-19 14:39

Young Chinese painters awarded at UNEP Headquarters 2012-07-17 15:56

Chinese paintings, calligraphy displayed in Cambodia to promote culture 2012-07-16 14:53

Chinese alcohol, Chinese spirits 2012-07-15 10:47

Passion for Porcelain 2012-07-13 13:26

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|