The relics of 9/11

Updated: 2012-06-18 15:00

By Patricia Cohen (Agencies)

|

|||||||||||

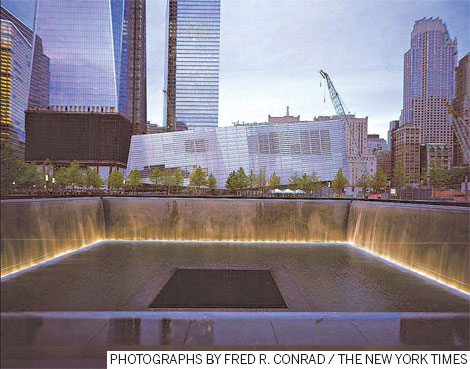

Unhealed wounds complicate the choices for a new museum

It seemed self-evident at the time: a museum devoted to documenting the events of September 11, 2001, would have to include photographs of the hijackers who turned four passenger jets into missiles. Then two and a half years ago, plans to use the pictures were made public.

New York City's fire chief protested that such a display would "honor" the terrorists. Groups representing rescuers, survivors and victims' families asked how anyone could even think of showing the faces of the men who killed their relatives, colleagues and friends.

The anger took some museum officials by surprise.

"You don't create a museum about the Holocaust and not say that it was the Nazis who did it," said Joseph Daniels, chief executive of the memorial and museum foundation.

In the end, the museum decided to display the photographs, but in shrunken form, the faces a little bigger than a thumbnail. And they will have evidence stickers from the F.B.I. attached.

Such are the exquisite sensitivities that surround every detail in the creation of the National September 11 Memorial Museum, which after eight years of planning is being built on land that many revere as hallowed ground.

Alice Greenwald, the director of the new museum, and her team must simultaneously honor the dead and the survivors; preserve an archaeological site and its artifacts; and try to offer a comprehensible explanation of a once inconceivable occurrence.

|

"Whose truth is going to be in that museum?" asked Sally Regenhard, whose son, Christian, a firefighter, died in the north tower.

Even the name - "Memorial Museum" - is something of a contradiction in terms. In the context of a memorial, for example, the five-meter, 1.3-metric-ton crossbeam where Mass was said every day during the cleanup is a sacred relic. In a museum, it is simply evidence.

"Museums are about understanding, about making meaning of the past," said James Gardner, who oversees the nation's legislative archives, presidential libraries and museums. "A memorial fulfills a different need; it's about remembering and evoking feelings in the viewer, and that function is antithetical to what museums do."

Sifting Through Pain

As the former associate director of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, Ms. Greenwald knows a lot about ghastly things. Yet even that museum did not have to wrestle with the challenge of being built where the horrors had occurred and while the families of victims were still grieving.

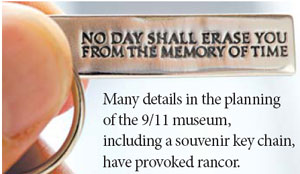

Many families are upset, for instance, about a plan to place about 14,000 unidentified or unclaimed remains in the museum below ground. The repository will be sealed off from everyone but family members. Visitors will just see a wall inscribed with a quotation from Virgil: "No day shall erase you from the memory of time."

Seventeen family members have filed suit against the city as part of an effort to reopen the decision. They view it as degrading to set the remains in a museum below ground. Rosaleen Tallon, whose brother, Sean, a firefighter, died in the north tower, said the insensitivity was mirrored in the museum's decision to stock its gift shop with $40 souvenir key chains engraved with the Virgil phrase.

"They're marketing the headstones of our loved ones on key chains,"she said. "How disgusting is that?"

But to Ms. Greenwald, the decision to keep the remains underground represented an effort to fulfill a longstanding promise to other families who had sought, above all, to ensure that the remains stayed at bedrock.

"It's been a very difficult, fascinating and challenging process"to juggle competing visions of what the museum should be, she said.

A subtle map of divisions surfaced that ran along class, geographic and political lines: New Yorkers found outsiders meddlesome; families of uniformed rescue workers were resentful of Wall Streeters' moneyed influence; critics disdained those willing to compromise.

But with a few notable exceptions, Ms. Greenwald has been widely praised for her curatorial judgment as well as for her diplomatic skills.

"She has handled this thing with sensitivity,"said Charles Wolf, whose wife, Katherine, was killed in the attack. "She is the one who gave us all confidence in the whole process."

Difficult Decisions

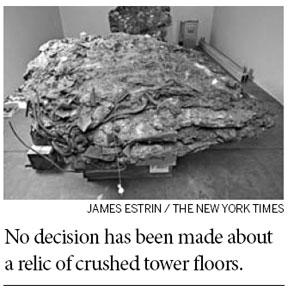

The museum has more than 4,000 artifacts, from a wedding band to a 13-metric-ton composite of several tower floors that collapsed into a stack, like pancakes, and then fused together. There are photographs of men and women jumping out of windows, burned and mutilated bodies,

scattered and blood-soaked limbs.

There are thousands of harrowing firstperson recollections, and photographs and videos from survivors and witnesses. Many victims' final phone calls were preserved. Flight 93's cockpit recorder captured the hijackers' last words and a flight attendant's begging for her life.

Which of it should be on display?

"We have to transmit the truth without being absolutely crushed by it,"Mr. Daniels, the chief executive, said. "We don't want to retraumatize people."

Curators reviewed hundreds of recordings. The family of Betty Ong, the flight attendant on American Airlines Flight 11, which hit the north tower, for example, gave the museum a tape of her calmly informing ground control of the terror transpiring around her.

"It's the most remarkable demonstration of professionalism under duress that I think anyone will ever hear, and they wanted us to include it because they felt it said so much about who she was,"Ms. Greenwald said.

The family of Mary Fetchet, a member of the foundation's advisory board, donated the recording of her 24-year-old son Brad's last phone call from the south tower, telling her not to worry.

A third recording was of a 911 operator tenderly trying to comfort a woman during her terrifying final moments.

As she listened, Ms. Greenwald kept thinking of a comment made by the museum consultant Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett. "I'll never forget it because it just ripped me apart when she said it, that we need to look at this kind of material as another form of human remains,"Ms. Greenwald said. "We need to use it judiciously."

In the end, they decided to make Brad Fetchet's and Betty Ong's voices available, and to archive the other. "This was not meant to be a public moment,"Ms. Greenwald said of the 911 call.

Reversible Choices

|

Over time the team also pulled back further from exhibiting graphic carnage. Ms. Greenwald explained that there were other ways to convey horror, as when it is reflected in the faces of witnesses. "The historical reality is that there were body parts littering Lower Manhattan,"she said. "We do not feel the need to display that."

Opinions about whether to include images of trapped victims leaping from the flaming towers were mixed. Ms. Greenwald and Mr. Daniels decided to use photographs, but not video, and only if the person jumping could not be identified.

And absent from the space so far are any "composites,"the chunks of compressed floors. Some families are concerned that despite assurances and tests, composites could contain body matter.

"Museum officials thought this was a very interesting exhibit,"said Diane Horning, who lost her 26-year-old son, Matthew. "To us, it was human remains."

Still, the material that will be on display can be devastating, and the architectural design includes "early exits"along the museum route, enabling distressed visitors to duck out.

Many of the decisions Ms. Greenwald and her colleagues are making today may be unmade in the future. Future curators will choose differently as time passes, anguish eases, and America's position in the world shifts.

As Ms. Greenwald said, "This is a museum without an ending."

The New York Times

Related Stories

Things they left behind 9/11 2011-09-09 11:54

A museum's masterpiece 2012-05-18 13:03

Nanjing University History Museum and Art and Archaeology Museum 2012-05-17 09:08

Glass artworks museum in Chengde, Hebei 2012-05-09 15:34

Museum architecture 2012-04-13 10:36

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|