100 days of madness for mangoes

Updated: 2012-06-10 08:01

By Jim Yardley (The New York Times)

|

|||||||||||

MUMBAI, India - Inside his office at Crawford Market, Arvind Morde is a bit harried. It is mango season, after all. A client wants to ship a box of mangoes to Germany, a gift for the Indian-born conductor Zubin Mehta. Another caller wants to send a box to Switzerland; still another, to Singapore.

For 92 years, his family has sold fruit, and Mr. Morde has learned that Indians, wherever they may be, enjoy a good mango, widely known here as the King of Fruits.

"It is the only fruit appreciated by everyone," Mr. Morde, 66, says.

India arguably has only two seasons: monsoon season and mango season. Monsoon season replenishes India's soil. Mango season, some say, helps replenish India's soul.

Mangoes are objects of envy, love and rivalry as well as a status symbol for India's new rich. The allure is foremost about taste but also about anticipation and uncertainty: Mango season in the region lasts about 100 days, traditionally from late March through June; is vulnerable to weather; and usually brings some sort of mango crisis, real or imagined.

|

In Mumbai, prices have spiked for the Alphonso, the variety of mango grown along the western Konkan coast. Cold weather interfered with the growing season, producing fewer (and smaller) Alphonsos.

In Mumbai, many people insist on eating Alphonsos and might even be offended by the suggestion that any alternative could suffice. In New Delhi, many residents favor the varieties grown in northern India.

Once, the Alphonso and other varieties did not begin appearing in markets until late March or early April. Now some growers are producing mangoes in February at prices that can approach $30 a dozen, compared with $9 a dozen or less at the height of the season.

Mr. Morde said the family would sell about $200,000 worth of mangoes this year, many bought by corporate clients, so selecting the right mangoes is paramount. "It is like buying diamonds," Mr. Morde said. "You segregate them, sort them out, as per the quality."

India annually produces about 15 million tons of mangoes, roughly 40 percent of global production. Mango exporters now do a thriving trade with several Persian Gulf countries, where more than six million Indians are working.

Perhaps the only force capable of resisting the Indian mango has been the American government.

A longtime ban on Indian mango exports to the United States ended with a provision in the civilian nuclear agreement in 2008, yet imports remain limited, largely because of American requirements on irradiation and other issues.

Which means that Mr. Morde cannot brighten the mango season of at least one person: his son. He lives in Massachusetts.

Sruthi Gottipati contributed reporting.

The New York Times

Today's Top News

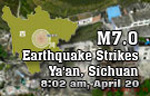

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|