Digging deep for a career in science

Updated: 2012-03-28 10:04

By Wang Kaihao (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

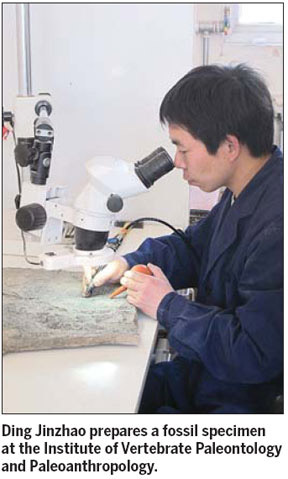

Working with the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, under the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), 35-year-old technician Ding Jinzhao is responsible for fossil specimen treatment.

He works on a panel led by Li Chun, a paleontologist who focuses on Triassic marine reptiles.

Under Ding's microscope, Odontochelys semitestacea, the oldest known extinct species of turtle, is silhouetted against a rock Li found in Guanling county, Guizhou province.

"When I cleaned one of its claws, which had hooks," Ding recalls. "I immediately realized it was not the species we thought it would be."

It took Ding more than three months to completely examine the piece. And although the fossil is of great importance to the study of the evolution of turtles, it is just another fossil for the experienced Ding.

Ding knew little about paleontology when he left his hometown in the countryside of Dazhou, Sichuan province, and went to Beijing in 1997. A fellow villager introduced him to the institute.

"I was quite interested in dinosaurs in my childhood," Ding says. "However, we didn't have access to more relevant knowledge in rural areas."

One of his major assignments in the next three years would be to build a dinosaur skeleton from fossils. He also occasionally takes part in scientific expeditions around China.

"It's more important and faster to learn in practice."

His job is to determine the fossil and clean sediment so it can be examined in greater detail.

It's not an easy job, he says.

"The rocks used to lie on the bottom of ocean, under high pressure, and thus they are very hard. Another difficulty is the color of the fossils and surrounding rocks are really close, although the fossils may be a little darker."

Ding's tools range from hammers and drills to dental needles.

Ding works eight hours a day, but it can take up to six months to put together a 3D specimen.

"The job is very challenging and interesting, and thus I don't get bored."

Ding earns about 6,000 yuan ($949) a month. He has refused offers from Peking University and several provincial natural science museums to work for them and earn more money.

However, Ding is still registered as a temporary worker rather than a formal employee of CAS. So are the other 30-odd technicians who work at the Changping research center of the institute. Most of them come from the countryside and none graduated from college.

Ding got a junior college diploma for paleontological fossil preparation from Capital Normal University in 2010, but he says it is far from enough.

The institution has offered some fossil-preparation technician positions to fresh college graduates in the past few years. But Li says this is not enough either, as you need a lot of practical experience to do the job properly.

"Many college students look forward to decent jobs in offices, and they don't want to become blue-collar workers like us," Ding adds.

In 2003, he married another technician, Wu Yong, who comes from Chongqing municipality. She is part of a panel that prepares dinosaur fossils from Shanxi province and the Inner Mongolia autonomous region.

"We sometimes exchange ideas at home," Ding smiles. "That makes the dinner-time talk informative."

They have a 7-year-old daughter and they live in a cabin in the backyard of the workshop.

"I don't expect any changes in my career," he says. "But I don't want my daughter to become a blue-collar worker like myself. At least, she should go to college and then work in an office."

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|