Eye spy

Updated: 2012-02-15 13:30

By Cheng Anqi (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

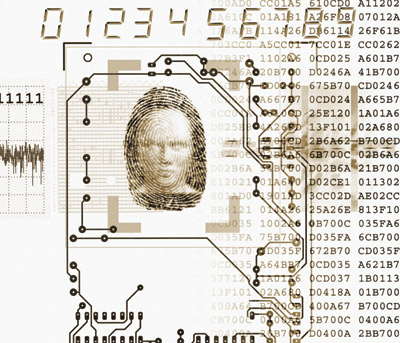

A new biometric camera and database network could make it hard for bad guys to hide. Cheng Anqi reports.

Li Ziqing felt he needed to do his part when authorities started a nationwide campaign to nab fugitives and kidnappers. The Center for Biometrics and Security Research (CBSR) professor and his team spent the following months creating a database enabling netizens to collect and share photographs, information and tips online.

"People can secretly snap and upload photos of people who appear suspicious or who may have kidnapped children," Li explains.

"The information will be cross-referenced with the database until the best match is found."

Every face is not only as unique as a snowflake but also measurably so.

"Most humans meet hundreds of thousands of people in their lifetime but can only recognize between 1,000 and 2,000," the 53-year-old says.

Human faces have hundreds of features. These are densest around the "golden" triangle of the eyes, nose and mouth.

Computers can analyze features and the angles between them, and store this information in a database with millions of faces. A photo of a person then can be matched with the most similar database entry.

This technology was used at the 2008 Beijing Olympics and 2010 Shanghai World Expo.

|

|

Li Ziqing is a facial recognition technology pioneer. Photo provided to China Daily |

During major events, thousands of attendees are photographed without their knowledge as they pass through security gates.

"But few of these images are high-definition, and children vary in age," Chinese People's Public Security University's criminal investigation department dean Dai Peng says.

"So it's fairly difficult to recognize a lost child who has grown up, because the child's features change."

An army of volunteers has been photographing children of various ages in the streets. Computer-generated 3D models then can predict what the children will look like in the future.

Another challenge to the technology is light, Li says.

Strong sunlight on people's faces changes cameras' pixel values, affecting recognition potential. So, eyebrows will appear lighter than cheeks, for instance, in glaring light.

Li used flash photography during trials.

"But participants said it's unacceptable to be subjected to a flash so often," Li says.

So, he started using near-infrared (INR) imagery, as the wavelength is closest on the spectrum to visible light.

"Near-infrared waves are microscopic," Li says.

"They're so small that you can't even feel them."

But before marketing their new technology, Li's team had to determine whether the surveillance system could isolate a face in a crowd.

It did.

First a team member looked at the camera, which recorded his information in the database. Then, whenever he looked at the camera, his image was cross-referenced with the database's millions of images.

Next, the system was tested in less-than-ideal conditions. The team member wore a disguise, a fake mustache and a pair of rimmed glasses.

"The Beijing subway is a superb test site," researcher Lei Zhen explains.

"Light is not always consistent, and the person may be obscured by shadows."

They then set up the surveillance system to target anyone who exits the subway.

The mass of people ebbed and flowed. To evade detection, the team member tried to blend into the crowd, but it was impossible for him to hide.

The camera not only identified him but also tracked him as he moved.

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|