Why we need to listen to Keynes

Updated: 2015-10-09 07:24

By Andrew Moody(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

Skidelsky thinks China was probably influenced by economist in formulating stimulus policies

Robert Skidelsky believes the world could enter "lingering" stagnation rather than rebound any time soon from the financial crisis.

The economic historian and biographer of the great economist John Maynard Keynes insists China's slowdown, the continuing euro crisis and anemic growth revive dark memories of the 1930s.

"It is like a lingering disease, what Keynes would have called a state of invalidism, rather than death.

"It (the global economic situation) is nothing, not buoyant, not anything. Just look at the growth rates."

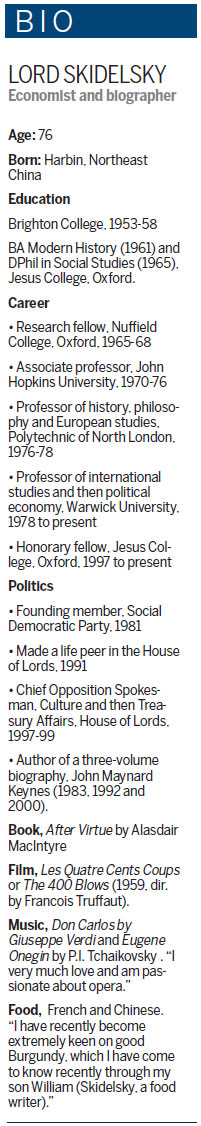

Skidelsky, 76, who was made a life peer in the 1990s, was speaking from a room adjacent to his office in Little College Street, a stone's throw from the House of Lords, where he sits as a crossbencher (independent).

He remains best known for his three-volume biography of Keynes, which was originally meant to be a 150,000-word single volume completed in two years. It eventually extended to more than a million words in three volumes published between 1983 and 2000.

Its author recoils from the idea that it is the definitive biography.

"It sort of grew and sprouted wings of its own. I don't think it is definitive. I don't think any really great person - and he was a great man and remains so - ever gets a definitive biography. People are always discovering bits and pieces," he says.

"Richard Davenport-Hines (Universal Man: The Seven Lives of John Maynard Keynes) has recently written a biography, for example, leaving out all the economics and focusing on his other interests."

With global deflation now seen as a big threat, Keynes is back in fashion after seemingly being consigned to history when the Chicago monetarism of Milton Friedman was in the ascendancy in the 1980s and 1990s. His return was heralded by Skidelsky's 2009 book, Keynes: The Return of the Master.

"The thing about economics, unlike the natural sciences, is that nothing really disappears. No ideas ever vanish because the context is always changing.

"When the world was concerned about inflation in the 1970s, they wanted a rationale for that and Milton Friedman provided it. Now we are concerned about depression, Keynes is again to the fore with all the theories about depression. There is constant turbulence in economic ideas which are never fixed and final."

Skidelsky was born in Harbin, Northeast China, in 1939 to a Russian father, whose family firm leased a coalmine from the Chinese government and a mother who had British nationality.

"I don't really recall this since I was only 3 when I left. My memories are stimulated by a photograph of me at my third birthday party with a sweet little girl all dressed up at our house in Harbin."

His family was interred by the Japanese and were taken to Japan, where they were eventually exchanged for Japanese internees in Britain.

"It was a stroke of luck that we were exchanged for some Japanese and then came to England," he says.

In the last 10 years, he has been back to Harbin twice to revisit his early childhood home.

"The exciting thing is that our house was still there. It was a rather grand house and has had a preservation order slapped on it. It had been taken over by the People's Liberation Army in the late 1940s and used as an administrative center. It is now dwarfed by large skyscrapers."

Skidelsky went to Brighton College public school as a boarder and to Oxford, from where he began an academic career at Nuffield College.

Apart from being a famous biographer, Skidlesky also had something of a parallel political career, being a founder member of the now defunct Social Democratic Party in the UK in the 1980s.

By the time Tony Blair rose to power in 1997, he had moved on to the Conservative benches and was an opposition spokesman in the House of Lords on culture and treasury affairs before being sacked by then Conservative leader William Hague after opposing the party line on the Balkans crisis.

Skidelsky, who also writes on China, thinks the government might have been partly influenced by Keynes, with economic policy in recent years often dominated by stimulus policies to raise aggregate demand and achieve growth targets.

"I hope Keynes has had some influence. I have always had very eager Chinese translators of the books that I have written."

He does, however, think the Chinese economy faces some difficult challenges.

"I think it is very difficult to restructure an economy and keep the old level of growth but it is something they have to do because I don't think they can afford the fallout of a substantial slowdown.

"They are running into problems with how the banking system works or doesn't work, the money being poured into state-owned enterprises has to be reduced and they can't keep going on forever as an export-led economy. There is more of protectionist sentiment in America and there has been some repatriation (of industry) back to the US."

Skidelsky is a major critic of austerity policies currently being followed by governments throughout Europe since he believes attempts to cut budget deficits just stymie growth.

"If the economy grows, the borrowing requirement will automatically shrink and so will the national debt. You don't control your revenues but you always control your expenditures. If you have a growth policy the deficit will come down."

He believes the obsession with fiscal deficits is wrongheaded because in economics they theoretically do not exist.

"In a sense there can't be a deficit because if you believe in double-entry accounting, an asset and a liability always balance. Government expenditure will also always be financed since a government cannot spend money it hasn't got. If it spends money, someone is financing it, either through taxes, issuing bonds or the central bank printing money."

Skidelsky believes some policymakers, particularly in Europe, are deluded, making reference to the recent Five Presidents' Report on Economic and Monetary Union, headed by EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker.

"They talk about the completion of economic and monetary union. Well, what language are they talking? It is almost a kind of fool's paradise."

He says this failing to face the reality of problems has led to the rise of extremist parties such as Syriza in Greece and Podemos in Spain, which he believes in itself echoes the 1930s.

"They are not so dominant at present but it only takes a real catastrophe to bring these extremist parties to the center."

Skidelsky says there may not be any return to economic normality for some time and that low interest rates and quantitative easing could prevail in a deflationary world.

"What is normal? A normal interest rate is one that works and produces relatively full employment. In terms of inflation or deflation, the 19th century as a whole was a deflationary period and so were the inter-war years, so it can all persist a very long time."

andrewmoody@chinadaily.com.cn

Today's Top News

Opinion: Opportunity knocks for EU and China over next five years

Yuan rises for 7th day in a row, highest level since August

Reforms spark legal brain drain

High-tech zones up the game

EU officials postpone visit to Turkey after attacks in Ankara

Documents of Nanjing Massacre inscribed on Memory of World Register

Xi congratulates Kim on WPK anniversary

CPC expels media exec over UK 'green card'

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|