Fragrant taste added to land of her birth

Updated: 2015-10-02 09:44

By Cecily Liu(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

Briton born in Shanghai makes Greek olive oil to those who appreciate fresh food

Chinese food has never ceased to fascinate Natalie Wheen, an old China hand who was born in Shanghai and grew up on Chinese food but rarely visited the country since leaving for Britain in 1957.

After a successful career as a radio music commentator in the United Kingdom, Wheen has gone through a significant career shift to run an upmarket olive oil business, Avlaki Ltd, and China naturally became a key market for her business.

"Good olive oil would naturally go well with Chinese food, because the Chinese people put so much care into making food that is fresh and flavorsome," says Wheen.

Amongst the Chinese dishes she regularly cooks at home with olive oil are steamed fish, stir-fried meat and vegetables, soup and stir-fried rice with vegetables and eggs. But to convince the Chinese consumer is altogether another matter, because olive oil has been widely available in China for only a few years and the limited supply is mostly comprised of mass-market brands.

"I really want to teach Chinese consumers about the difference between high quality olive oil and mass market brands. I do recognize not everyone in China will be able to afford it, as it is targeting a distinct market, but I believe the potential is there," says Wheen.

Wheen's family has had a long and deep connection with China stretching over generations, starting with her great-grandfather Edward Wheen, who arrived in Shanghai in 1874 as a businessman, focusing mostly on imports.

Many years later, during the Great Depression, the Wheen company went bankrupt, and her father started a career working for the British chemical company Imperial Chemical Industries in China.

Wheen's mother's side of the family came from Russia, and an uncle, Colonel Alexander Tatarinoff, who was military attache at the Russian Embassy in Beijing in 1917, and after leaving his native country ahead of the revolution, spent the rest of his life in China.

Her parents married in Qingdao in 1937, and Wheen was born in Shanghai in 1949. Two years later, Wheen's family moved to Hong Kong, where they stayed until 1957. During those years Wheen's nanny, whom she called by the polite term "amah", cooked a great array of Chinese dishes, and one of her favorites was chicken soup with spinach and lettuce.

Wheen's father was the company secretary of the chemicals company ICI, so her parents spent most evenings at parties and left her in the nanny's charge.

"She would always prepare some Chinese food for me to have with her, so my No 1 comfort food has always been Chinese cooking. I think my palate has been trained to the subtleties of tastes and textures of Chinese food."

These fond childhood memories of China have cultivated a sense of belonging in the country for Wheen, and when her family moved to the UK she initially felt sad. "I hated coming to the UK, as February in England is cold and wet," she says.

She says she still has many objects at home to remind her of China, which she took when she left the country, including silk fabrics, cushions, a jade tree with green stones as leaves, and a long table made of dark colored wood in the Chinese style.

After starting a new life in the UK, Wheen studied classical music at the Royal College of Music, and in 1968 started work in broadcasting. She started by presenting programs on classical music and arts, initially at Radio 3 and later at Classic FM.

In 1997, Wheen returned to China for the first time since she left, work on a documentary on Chinese food. "I was immediately at home, in spite of the extraordinary changes," she says.

During the time she spent preparing for the program, she stayed in Hong Kong to find out how the local population eats nowadays, how they buy food and cook it. Her love for fresh Chinese cuisine grew.

"What I discovered is the love for fresh food in China, because in China people buy food in the wet markets. If you want a fresh chicken, you can watch it being killed just before you buy it, and you know it is absolutely fresh," she says.

"The shopping streets are full of freshness. For example, a good Chinese housewife would buy some food to cook for breakfast, and then she would later go to the market to buy some food to prepare for lunch, and then the same for supper."

This continual striving for fresh ingredients is coherent with the philosophy of Avlaki, which makes olive oil by pressing the olives the day after they are harvested, and then bottling the oil a few weeks later.

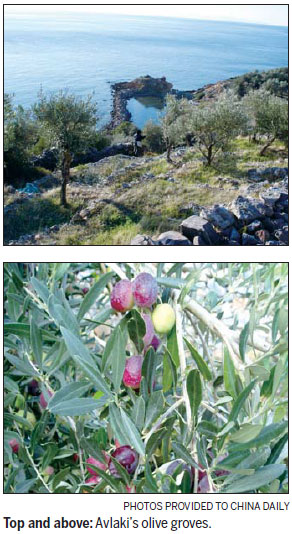

Despite Avlaki's success, Wheen says the journey of creating this business was almost an accident. It started in 1996 when she and a painter friend, Deborah MacMillan, pooled resources to buy a small, run-down property by the sea in Greece as an escape from the stress of their professional lives.

"We have been going on holiday to Greece for years, and we then had this idea of buying some land so we can have a place of our own," Wheen says. But what they did not realize is that in order to have the legal right to restore the property, they needed to buy more adjoining land.

They bought several adjoining parcels, and together the land had about 800 olive trees. This inspired them to start up an olive oil business, because they realized that the uncultivated olive trees were a great asset in themselves.

They realized that their olives, long left uncultivated, were different from neighboring olive oil farms where trees are grown with heavy use of pesticides. Wheen says the nearby farms' trees were wrecked by aggressive harvesting, and newly harvested olives were crushed when they were dumped into massive sacks and processed in unsanitary mills.

"We took control of every aspect of production, harvesting the olives by hand, removing the blemished fruits and taking the rest to a clean mill in shallow crates to avoid bruising," Wheen says.

The farm is also grown in a strictly organic way, and now the fields bloom with lots of wildflowers and teem with wildlife, she says.

All this makes Avlaki olive oil expensive, with a 500 milliliter bottle selling for 18 pounds ($28; 25 euros) in the UK, compared with, for example, the British supermarket Waitrose's own branded olive oil, which sells for 2 pounds for a 500 milliliter bottle.

Avlaki's olive oil is only sold at high-end food stores or online. Even so, things got busy, and a few years ago Wheen made a decision to focus full time on her company.

More recently, Avlaki started overseas distribution in Finland, Iceland, Dubai, Kuwait, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Estonia, among other countries, and now exports account for about half of sales.

Realizing that China is a crucial market with great potential, Wheen went to Shanghai last year to exhibit the olive oil at the Food and Hospitality China show for 10 days, as a part of a trade mission organized by the UK Trade & Investment office and the China Britain Business Council.

Avlaki has also established a partnership with Mao Xi Trading of Shanghai to help distribute its olive oil in China.

"We have a quality brand, and we know that discerning Chinese are well aware of the importance of buying the best, especially where food quality is concerned. We believe the Chinese market will appreciate the quality of what we present."

cecily.liu@mail.chinadailyuk.com

Today's Top News

Hot spots impose caps on visitor numbers during holiday period

Initiative looks to UK maritimes services

Movies Midas touch anticipated amid economic slowdown

Surfing in the air brings Internet to the skies but concerns linger

Russia starts airstrikes against terrorists in Syria

Li: China will meet main goals

Xi celebrates National Day with ethnic representatives

China marks Martyrs' Day at Tian'anmen Square

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|