Farewell, match

Updated: 2012-10-12 11:02

By Yang Yang (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

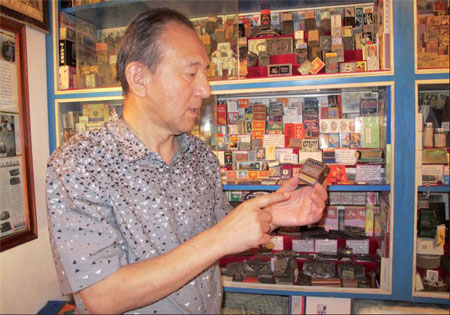

Li Fuchang regards the box with a miniature abacus outside as his most precious collection. Photos by Yang Yang / China Daily |

|

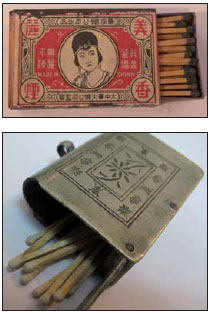

Top: The matches made under the cigarette brand Meilixiangyan have been popular for about 20 years. Above: The box into which matchboxes are put are made of materials such as steel and bronze. |

Commercial realities catch up with one of the simplest tools ever invented

When a grand old match company announced recently that it was closing, it ignited a firestorm of nostalgia over a humble item that has played a key role in Chinese people's lives for nearly 150 years. Botou Match Company in Hebei province, formerly one of the largest match factories in Asia, went bankrupt after being in business for a century. The main accelerants in the company's decline were the fact that fewer people need to start fires these days, and that those who do are plumping for the more convenient lighter.

The news of Botou's demise got people reminiscing not only about matches but the little boxes they come in, which not only hold a couple of dozen fire starters, but that, with their finely printed labels, embody decades of history.

So in the following weeks a 66-year-old man in Beijing who is an aficionado of matches and matchboxes became a magnet for the media as he showed them his private museum devoted to matches and fire.

In a first-floor apartment of less than 60 square meters south of the Temple of Heaven in Dongcheng district, Li Fuchang's museum covers just 7 sq m in four glass cabinets.

"My museum, although it is called museum of matches, is not only about matches but Chinese fire culture," Li says, as he begins to introduce his treasures one by one.

Li started to collect matchboxes when he was 6, at the same time as he developed an interest in painting. His father was running a stationery shop that sold brushes, paper and ink as well as calligraphy works and paintings. They lived in a neighborhood near the current Qianmen Street, next to the Beijing Match Factory.

One day three artists moved into the street. During weekends the three would go on picnics with friends, where they would swim and draw. It was as much their romantic lifestyle as their drawing that inspired the young Li.

"I was only a kid then and had no spare money to buy painting books, so I collected packages of various goods and tried to draw those pictures on the packages. And matchboxes became one of my favorites."

At that time several of his classmates earned pocket money at home by working for the match company. They worked with matchbox labels, and gave any that were faulty to Li, for whom collecting matchboxes and labels would become a hobby. He now has a collection of more than 100,000, some of them produced in the late 19th century.

"These matchboxes are witnesses to history, and each of these beautiful pictures tells a fantastic story," Li says.

One of the matchboxes was made in the early 1930s by Liu Hongsheng, widely regarded as the king of matches.

The match, invented in 1827 and produced on a large scale first in Europe, was introduced to China by the British ambassador to please the Daoguang Emperor. Matches were first imported into China in 1865 and sold at very high prices. Chinese people called them yanghuo, or foreign fire, denoting their exotic origins.

Until 1932 Japanese and Swedish matches held sway over the market. Chinese match producers were small, their factories were poorly equipped and the product of inferior quality. Liu, then a successful businessman, created a trust by uniting the small producers and made matches under the brand Meilixiangyan (beauty and cigarette), and it was popular for about 20 years.

Fascinated by these beautiful matchboxes and their stories, Li, did copious amounts of research on their history, and gradually expanded his collection to other perspectives of fire culture in China.

His collection includes small, intricately decorated etuis made of materials including steel, bronze, wood and ivory that people once used to protect their flimsy matchboxes.

Li picked a small box he regards as "my most precious one", and says: "The outside of the box is a miniature abacus, and you can actually use it to compute. And another special thing about it is that on one side of the box is the signature of the maker, which is very rare for such boxes."

The collection includes matchboxes in myriad shapes, dimensions and materials. One box is in the form of a house, one is like a column, one is made to look like lipstick, one is a parallelogram, some are made of glass, and there are matches designed for special use, such as storms, exploration and war.

Then there are ignition tools used throughout human history, such as flints, yangsui (a bronze concave mirror, which was first used by ancient Chinese people in the Western Zhou Dynasty (c. 11th century-771 BC) to light a fire, fire strikers and lanterns.

Twenty years or so ago, as more and more people learned of his collection and asked to see it, Li found it extremely inconvenient to have to keep the matchboxes and matches in a box under his bed and decided to put them in glass cabinets, so he opened the museum.

To better protect and display the collection, Li has used the expertise he has picked up by visiting museums, including using cool-light lamps in the display room.

In 1997 he became a member of the British Matchbox Label and Booklet Society, and 10 years later he organized an international exhibition of matchbox labels in Capital Museum in Beijing, presenting this beautiful cultural tradition to a wider audience.

Although matches have not quite become historical relics, there are plenty of people around, young and old alike, for whom matchboxes hold a certain degree of nostalgia.

In one of Beijing's most well-known tourist spots, Nanluoguxiang, three shops sell matches that young people in particular seem to like.

"Usually young people are willing to spend 10 to 20 yuan ($1.60-3.20, 1.20-2.40 euros) for large boxes of matches that often contain 10 small boxes to give friends back home as a gift," Li says.

Obviously, match producers have studied what young people like these days. Those born in the 1980s and 1990s are clearly still familiar with matches, which were widely used when they were kids. A desire by such people for a mix of creativity and nostalgia can be fulfilled in areas such as Nanluoguxiang and 798 Art Zone, also in Beijing.

They find matchboxes decorated with cartoon images that most young people would be familiar with, such as the Japanese Doraemon, popular wordplays from the Internet, images of celebrities, such as the Apple cofounder Steve Jobs, and famous quotes, such as those of Mao Zedong.

"I think I will buy those with Marilyn Monroe's posters," said Wang Shancun, 37, from Hunan province, as he visited Xiaoqijia (Little Seven's Home) match store in Nanluoguxiang. The best-selling ones are those with Hollywood stars, Steve Jobs and Beijing scenery, a cashier said.

Li, with his museum, has a keen eye on younger generations, too.

"I want to leave something to younger generations. Today we don't use matches as much as before. Eventually matches will become historical relics. I just hope that young people can learn about China's fire culture, whether they come to visit my museum or see the pictures online."

yangyangs@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 10/12/2012 page26)

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|