Burning passion

Updated: 2012-07-20 12:22

By Zhang Lei (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

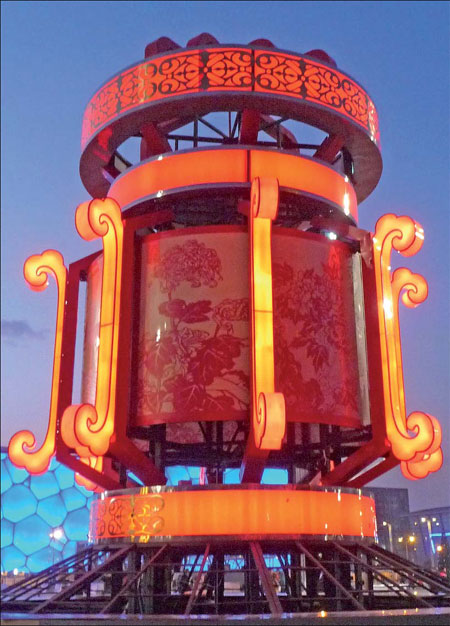

Traditional Beijing palace lanterns are often six-sided, with each side painted with Chinese watercolor drawings. Ji Lu / for China Daily |

Craftsmen struggle to keep traditional Chinese lanterns alive

When Song Dynasty (960-1279) poet Xin Qiji spotted the palace lanterns adorning the streets during a Lantern Festival, he was stirred to pen these immortal lines: "Night lights a thousand trees in bloom, a shower of stars blown by the east wind." But if Xin were alive today, he would no doubt join many other people in lamenting the dying art of making one of the most sophisticated forms of the Chinese lantern.

Zhai Yuliang, who has inherited the skills needed to produce the Beijing-styled palace lanterns, is considered one of the last few craftsmen who can handle the intricacies behind the delicate art.

Chinese palace lanterns are usually large, with painted silk or glass panes inlaid around its rosewood or sandalwood frame. Traditional Beijing palace lanterns are often six-sided, each side painted with Chinese watercolor drawings often in symmetrical display. The top and bottom openings are carved in patterns linked with good fortune.

Zhai's "belle" painting lanterns are among his most popular items. The lanterns can be twirled, casting the dim light of its bulb against the ceiling to make it seem as though its painted beauties are whispering to their owners.

Zhai usually takes about eight to 12 days to complete one lantern but he says the joy of creating one is "beyond value". More than 100 steps are involved in making each of them, and his workshop can churn out 100 lanterns a month.

"When times were good, we had as many as 300 workers at our factory. But now there are only 50 left because many workers are leaving for higher-paying jobs or have retired," Zhai says. "There are only 10 people working on the production front line and everyone has to do several jobs at the same time. That is why I am also the sales manager of the factory."

The area surrounding Beijing's Dengshikou subway station was once a hub of the country's finest lantern makers.

When the demand for palace lanterns boomed at the end of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), Zhai's Wenshenzhai family workshop incorporated the Huameizhai and Zhimeizhai ones to become the leading lantern maker. Their craftsmen made lanterns for the Empress Dowager Cixi.

Before the technique and skills needed for the lanterns spread at the end of the Qing Dynasty, Beijing palace lanterns were made exclusively for the imperial household. Originating in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the lanterns were used in imperial decorations and celebrations for many centuries.

In 1915, the Zhai family's palace lanterns were presented at the Panama Canal opening celebrations and won a gold award at the Panama Pacific International Exposition. The third-generation maker says he is proud to be one of the few craftsmen of the disappearing art.

"The artisans here are basically more than 50 years old on average. Young people are difficult to recruit," Zhai says. "In the 1980s, young people felt honored to work here at our factory and many even pulled strings to get here."

Ma Yuanliang, a 70-year-old master craftsman of Beijing palace lanterns, has no apprentice to pass on the art.

"It takes at least three to five years to master the basics of the work, and a pre-work design is crucial for making a big palace lantern. When there is no design, there is no future for the palace lantern", he says.

Zhai's lanterns also are facing competition from mass production lanterns. The Gaocheng lantern group is one of the biggest mass producers of palace lanterns. Zhang Qiang, the sales manager of Gaocheng Palace Lanterns Design & Development Co, says the group has more than 300 kinds of lanterns, with an annual production capacity of several million.

"Our biggest clients are big hotels and Chinese-styled shopping malls, but they usually buy cheaper lanterns," Zhai says. His team is now making every effort to create new styles to meet the new demand and changing tastes of their clients.

The yunhezimudeng (), a big lantern with its main body sporting several other small, independent lanterns attached on top of each fold, is most popular among hotels and tea houses. Zhai says its grand yet sober design is best suited for building an imperial-like atmosphere.

The management of the Prince Gong's Palace () historic site in Beijing, after consulting experts on the former setting of the lanterns on its grounds, purchased several orders from Zhai to make the lanterns as they were originally displayed.

Although the art of making palace lanterns was listed on the national protection list of intangible cultural heritage in 2006, sales have relied mostly on direct orders.

"Most of these are placed by old customers from the domestic market in direct contact with us. But during our heyday, we were export-oriented, taking orders mostly from trading companies," Zhai says. "High taxes are also a big factor constraining our development, with the enterprise income tax now as high as 17 percent. We need support from the government".

Palace lanterns do not come cheap. A yunhezimudeng lantern usually costs 3,000 yuan ($470, 383 euros) to 5,000 yuan, with some top quality ones sold at 10,000 yuan each.

Zhai says he is also producing cheaper red lanterns that are easier to make and sell.

Despite the difficulties and barriers ahead, Zhai has started to work on ways to save the old art. He is already creating new patterns. During the past two years, Zhai, along with his team, has developed ball and peach-shaped lanterns that are small enough to fit in private homes.

"We have also started to trace and record every existing artisan willing to pass on his work on palace lanterns, as most of them are 70 to 80 years old," he says.

"Interviews with these old artisans are tough, but I have a responsibility to shoulder."

zhanglei@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 07/20/2012 page26)

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|