Double dribble

Updated: 2012-03-23 11:08

(China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

Overcoming different attitudes, language and culture is far from a slam dunk

|

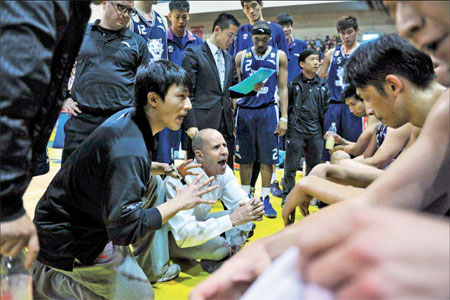

Head coach Brian Goorjian gives instructions to the Dongguan Leopards in a game against the Shanxi Brave Dragons in the CBA league. [Provided to China Daily] |

Coaching basketball is hard enough, but try moving from the US and plying your trade in China to see just how tough it can be. Foreign coaches are up against a language barrier, a new culture, different rules and norms, players who are, at times, suspicious of the newcomer and poorly trained, and quick-tempered management. It's a high mountain to climb.

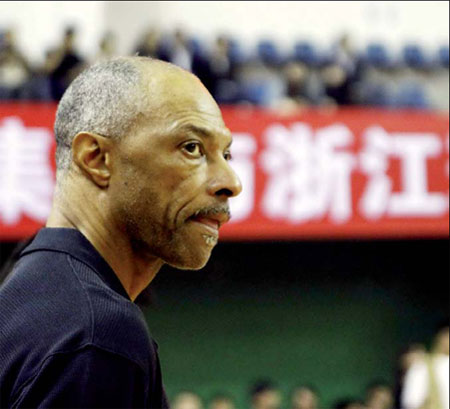

"I'm telling people, 'I've got a head full of grey hair', " says Jim Cleamons, head coach of the Zhejiang Lions in the Chinese Basketball Association.

|

Jim Cleamons is head coach of the Zhejiang Lions. [Provided to China Daily] |

All but Donewald remain, but considering the challenges they faced, one out of four is pretty good.

Can we talk?

|

|||

With two years at the team's helm, and three in total with the organization, 58-year-old Goorjian is the dean of CBA coaches from the US. He says his team's interpreter is so good, he considers him not just a colleague, but a friend.

Even so, Goorjian finds one of his key strengths as a coach - an intuitive ability to connect with players on a personal level - rendered useless.

"I'll say 'Hey, let's me and you go have a cup of coffee,' and then I go sit down and I find out that he's got a problem at home with his wife, or he's been thrown out of the house, or the kid's upset," Goorjian says. "You find something out like that. Or 'Hey coach, you've been in me too much, I'm losing my confidence' - that kind of conversation. That person wouldn't say it to me if there was another person involved and I wouldn't ask those questions."

On the court, the language barrier can eat at a coach's ability to convey the nuance and emotion of his message, and that's assuming the correct message is even being sent.

"If I want to say (to the interpreter) that you need to tell this kid he needs to get back on defense, and it's three times in a row - and then the guy turns around and says it in a polite (manner). Or maybe he turns around and says 'This guy doesn't know what he's talking about," Goorjian says.

"When I talk to the other Western coaches, they'll say (the same thing). Based on the kid's reaction, I don't know if (the interpreter) is saying what I said."

Cleamons, whose former jobs include time as an assistant at the Los Angeles Lakers under Phil Jackson and head coach of the Dallas Mavericks, worked with an interpreter while conducting coaching clinics in Japan some years ago, and says he learned a few tricks. He aims for a specific rhythm and cadence in his speech that he hopes is universally understood, and tailors his instruction to be less technical and more broad.

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|