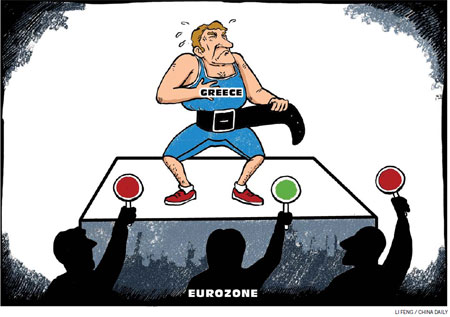

For everyone's good, let Greece go broke

Updated: 2012-02-24 10:40

By Giles Chance (China Daily European Weekly)

|

|||||||||||

|

"Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning."

When Winston Churchill spoke those words in London in November 1942, referring to a British victory in North Africa, he believed that once Germany had declared war on the United States at the end of 1941, British victory was assured.

But when we think about Europe today, it is unclear exactly how and when the crisis that has overtaken the world's largest economic region will end.

This extraordinary situation results from the paralysis of the European leaders, who seem unable to grasp and act on the seriousness of the economic and financial realities that must be dealt with for disaster to be averted and for financial stability to return.

China, as a major economic and financial power and a large exporter to Europe, is greatly affected by the European situation. A long European economic recession, which seems likely in view of the budget cuts to come in France, Italy and Spain (about half the euro area) will shrink China's largest export market. And many Europeans, like others around the world, are shocked at the sight of Europe, one of the world's richest regions, asking China for large cash hand-outs to prevent European bankruptcy.

How and when will the European crisis end? Can we even say that we can see the end of the crisis? How should China react?

It is becoming clear to most people that after the European authorities approved the 130 billion euro Greek aid package that was agreed to by the European Union in October, Greece is still unlikely to be able to repay its debts. Greek default seems inevitable. Given the social disruption and pain that the Greek austerity program is bringing, perhaps this may be as well. It is becoming clear that Greece needs to devalue its currency to kick-start its economic recovery.

While Greece remains in the euro system, the devaluation that would restore Greek external competitiveness can only take place through tax increases or spending cuts. These cuts eliminate the prospect of economic growth on which Greek recovery depends. So it seems only a matter of time before Greece announces it is leaving the euro system and will readopt its own currency.

Greece abandoning the euro and a new, devalued Greek currency will immediately increase the price of the country's imports by 50-60 percent, reduce the value of Greek assets to outsiders by the same amount, and may also encourage Greece to cancel repayment of its euro debt (which would increase greatly in value if Greece devalued its currency). But although a Greek default would be extremely painful in the short-term for the Greeks themselves and for investors in Greek assets, it would augur well for a resolution of the euro crisis, because it would send a clear and important message: Greek debts are too large.

Greece has to default in order to lighten its debt load, and discover the economic growth that can put its people back to work and rebuild the country. In fact, the same rule applies, in varying degrees, to other euro countries: Portugal, Spain, even Italy and possibly Ireland. Their debt loads are also too large given their poor growth prospects and uncompetitive economies. Cutting spending to reduce debt cuts growth and increases unemployment, hardening resistance to reform and in fact making it more difficult to repay debt. The best and possibly only way forward for Europe is to reduce the quantity of debt in troubled and highly indebted economies to an amount that allows economic growth to restart.

The resolution of the euro crisis depends on European leaders recognizing that the debts of weaker euro members, which are strangling Europe's growth prospects, must be cancelled or rescheduled. This means a series of country defaults that are managed by the European authorities with agreed debt restructuring schedules. At the same time, the banks that own the cancelled or rescheduled debt must be forced to write their holdings of overvalued debts on their balance sheets down to their correct values.

Euro debt is held mainly by banks based in euro countries led by France, Germany and Britain, but US banks also have a significant exposure. This writing-down exercise will severely damage the balance sheets of many big European banks. They must be recapitalized at the same time as the debts are written down, either by private investors, or by the State, or by both. In many previous financial crises caused by excess debt and over-leveraged banks, such as the Asian crisis of 1997-98, debt forgiveness and rescheduling has been an essential part of recovery.

Some will ask why steps to cancel or reschedule the huge amount of euro debt have not already been taken. The answer is that the leaders of the European banks, who are politically very powerful, do not want to take huge losses and recapitalize their institutions, because many will lose their jobs as a result. They prefer to try to muddle through the problem so they can take their losses steadily, without the need to change their ownership or management structures. Nor do the euro bank shareholders want to take large losses.

The bankers and the shareholders are supported by the leaders of the European countries who do not want their big banks being threatened by collapse, and dislike the idea of foreigners having some control of their banking systems. But European leaders and bankers need to learn from the Asian response to its financial crisis 15 years ago. In particular they should learn from the successful Chinese bank restructuring and recapitalization exercise that started in the late 1990s, which produced a banking system strong enough to absorb the 2008 credit crisis.

Deep euro debt restructuring and widespread euro bank recapitalization are necessary to bring an end to the crisis. But on their own these steps are insufficient to create a strong euro system. Euro countries need to make major changes to improve their economic competitiveness. Cutting tax on small enterprises, changing labor laws to allow much greater flexibility for workers to move between jobs, and for employers to take on or let go staff, removing the compulsory (and ridiculous) 35-hour European working week; these are some of the steps that European governments and the European Union itself need to act on in order to allow the weaker members of the euro to compete within the system, and not be destroyed by it.

To be fair, an agreement for member countries to carry out deep structural reforms was implicit in the original euro agreement. But in the wild economic expansion and asset bubble that started in 2002 and 2003 based on free credit from the US Federal Reserve, these commitments and promises were forgotten.

Sadly, the bad news is that the links between the euro banks, euro bank shareholders and the political leaders of Europe are probably strong enough to prevent the full debt restructuring and bank recapitalization that would start the process of healing and rebuilding through new economic growth. Instead, we may see a continuation of the slow death that we are watching in Greece.

The weaker southern European countries that have adopted the euro - Greece, Portugal, Spain and Italy and Cyprus - all have debt loads that are too large to allow their economies to grow. As recession drags on, and unemployment continues to rise, social unrest will begin to spread. At some point the markets may decide that the situation cannot be sustained, so that a severe market crisis forces the only solution to the euro crisis - cutting and rescheduling debt, recapitalizing banks and improving economic competitiveness.

While it is unclear exactly how and when the European crisis will end, it is clear that it is closer to the end of the beginning than to the beginning of the end, and there is a long way to go yet. When you consider how far Europe's leaders are from recognizing the solution, and the difficult steps to be taken to cut European pensions and wages to restore competitiveness - steps that are certain to provoke social unrest in many European countries - it is obvious that at this stage China should not allow itself to be dragged into European "solutions" that are not solutions at all, but that merely delay the inevitable. Senior Chinese government officials have already correctly remarked that Europe is rich and strong enough to solve its own problems. But once the Europeans themselves have started to set their own house in order, there will be time for China to become involved.

Meanwhile, the negative impact on Chinese exports from European recession will be felt this year and next, but the impact is manageable given the strong growth of China's domestic consumer demand and the economic strength in other Chinese export markets, particularly in the rest of Asia and so-called emerging markets such as Africa, South America and India. Predictions by the International Monetary Fund and others of Chinese economic collapse as a result of Europe's economic problems are overstated, perhaps for reasons that serve Europe's and the IMF's own interests.

The author is a visiting professor at Guanghua School of Management, Peking University. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|