Circle of life

Updated: 2012-02-17 07:48

By Ji Xiang (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

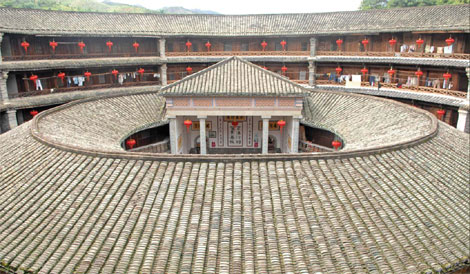

Tulou, or earthen buildings, are communal residences in a circular shape for housing extended families in the country's southern areas. Provided to China Daily |

Traditional Chinese dwelling offers insights to living in harmony

Think about colossal architecture in the ancient West and the palaces of kings and queens come to mind. To many Westerners, the Chinese epitome of such buildings lies right in the heart of Beijing - the Forbidden City.

The home of the Chinese emperors still displays the core tenets of traditional Chinese architecture, but deep down in China's southern provinces a less known but no less impressive structure has been providing an ideal form of housing for generations of farmers.

Tulou, or earthen building, is a communal residence usually in a circular shape that houses extended families.

Various types of tulou are scattered in different parts of the country, but most of them reflect the communal form of living and are designed to house hundreds of people around a central courtyard.

The ones in Fujian province were even listed as part of a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2008.

Tulou are usually made of clay and their walls are thick enough to defend attacks from intruders in times of unrest.

Some of the structures are also part of the heritage of northern migrants. When they first arrived in the mountainous south regions, they built these fortress-like homes to beef up their defense.

"The earth used to build tulou is easily accessible and they are technically not difficult to build," says Shi Jianguang, a professor from the School of Architecture and Civil Engineering at Xiamen University.

"It was very economical to build these. Wood and bamboo strengthened the building. Some stood well against earthquakes. The foundations of the buildings were made up of large stones and well above flood levels. Roofs also reached out for at least three meters to divert rain away."

In many ways, the earthen houses demonstrate how Chinese people evolved with nature and their own social needs. Blood relations and ancestral traditions were a top priority. Thriving families were also celebrated. The grandeur, scale and beauty of the tulou were necessary to display the social status and success of the Chinese clans inhabiting them.

Qiu Xi, 77, a native of Shangrao in Jiangxi province, remembers the vividly life inside the earthen houses.

She was born in a tulou and lived there until she was 70 years old and she knows every nook and cranny of the structure.

"There were about 20 households in total and life was very noisy," Qiu says.

The houses were usually made up of three stories and were round or square shaped.

There was one big entrance to the building and the rooms were connected with corridors in the front. As a result, dwellers walked past neighbors' rooms and around the whole building easily and quickly, "enhancing the joy of living in such a community".

"We paid visits to our neighbors very often and children were lucky enough to enjoy the food cooked by other families; celebrations were commonplace too. Whenever someone had a problem, we all worked together to offer solutions, so it felt very warm to have so many people you can rely on and seek for help," she says.

Tulou rooms on different floors were designed with specific purposes. In most cases, rooms on the first floor were used as kitchens, rooms on the second for storage, and rooms on the third as bedrooms. The value of such a design suited the natural living conditions of the area and was the result of the ingenuity of generations.

Ancestor worship formed a large part of tulou life. The location of the ancestral hall differed from building to building, but the area remained in the central part of each earthen house. Some were built in the center of the courtyard, while others faced the main entrance directly.

"There was usually a long table against the wall, on which people put candle holders, incense burners and plates of offerings. Red couplets hung above the table, which normally carried words of blessing. The ancestral hall nowadays serves as a public area for events such as weddings and funerals," Qiu says.

Amid changing times at the beginning of the 20th century, some of the earthen houses also installed Western building elements. Corridors, columns, domes, doors and windows were decorated with Western carvings and paintings. Nowadays people can still notice aspects of religious art in the building styles.

The earthen houses have become a major attraction for tourists but the original style of the houses has changed in some places.

"Not many people are living there any more," says Hong Zhangren, from Fujian.

"I could not even see any planting fields outside the buildings. I thought they might still rely on their crops but it seems that most of the former dwellers have abandoned their old homes and are making a living in the modern world."

"My sons and daughters have moved out to live in the towns, and people of my age need special care, so I went to live in the town too," says Qiu, who moved out of her tulou several years ago.

Well-known tulou areas include Longnan county in Jiangxi province, the city of Meizhou in Guangdong province and Yongding county in Fujian province. Tulou sites such as Hua'e Lou in Meizhou are open to visitors and still offer a peek into the lives of residents.

Former tulou residents like Qiu might also be happy to know that local authorities are helping repair the old houses of her time. Museums on the buildings have been set up, with some using the main body of the earthen structures.

"We can reflect on the results of modernization and ecological construction ... The earthen houses offer an important reference to us, in terms of seeking harmony between humans and nature," Professor Shi says.

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|