Credit crunch

Updated: 2012-01-06 08:53

By Andrew Moody and Hu Haiyan (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

Manufacturing center faces shutdowns as private moneylenders demand loans be repaid before Chinese New Year

Small businesses in China could be facing their bleakest Chinese New Year in more than 30 years - up to 20,000 businesses in the city of Wenzhou, one of the country's main entrepreneurial centers on the east coast, could suspend operations or close down altogether over the next month, according to a leading local business organization.

| ||||

Now many of the moneylenders - often consortia of other small businesses - want their money back.

It is traditional in China to settle all debts before the beginning of the Chinese New Year, which falls on Jan 23 this year.

Zhou Dewen, head of the Wenzhou Small and Medium-sized Business Development and Promotion Association, believes one in 20 of Wenzhou's small businesses could face closure.

"I believe it will be the worst Spring Festival since reform and opening-up more than 30 years ago because small business entrepreneurs are facing greater pressure than ever to pay back their loans and the profits from the manufacturing industry have been much reduced," he says.

Wenzhou, which is in the prosperous Zhejiang province, and the plight of its small businesses has been in the international media spotlight for many months.

The city, which has a population of 9.1 million and is famous for producing spectacles, cigarette lighters and shoe wear among dozens of other such products, is seen as a bellwether of the Chinese economy as a whole.

Many businesses have been hit hard by the economic crisis which has affected exports and up to 100 business owners are believed to have fled the country as a result of not being able to repay loans to moneylenders.

One of the most high profile of these was Hu Fulin, president of Center Group, one of China's largest spectacle makers, who absconded to the US in September. There have also been a number of suicides.

Until recently Wenzhou, a former treaty port and a city largely unknown outside of China, basked in its reputation of having more millionaires per capita than any other Chinese city and some of the country's most expensive real estate.

It was one of the first cities to develop a private economy in the wake of reform and opening-up led by Deng Xiaoping in 1978.

Despite designer stores like Gucci and Bentley car showrooms, there is now more of a chill in the city, which is some 600 km south of Shanghai, despite its mild winter climate.

Hu Xucang, the 36-year-old president and CEO of Aroundasia, a Wenzhou private equity company, says many of the city's small business owners feel trapped by their circumstances.

"They feel they have no choice but to borrow from underground lenders. If they don't, they will die today. By borrowing money, they just have a chance of not dying tomorrow," he says.

Hu, who has a suite of modern offices in the Financial Center Building in Chezan Avenue, is himself a successful entrepreneur.

Hu, who set up a plastic pipes business in his early 20s, which now employs 800, and his private equity fund has 5 billion yuan to invest, says there is now a big mismatch between the funding available and the needs of businesses.

"One of the major problems is that those in traditional manufacturing businesses have diversified into other areas such as real estate and high-tech businesses. All these sectors need long-term finance but all they can get is short term and high interest funding, which is why their cash flow is so damaged," he says.

The Chinese government has recognized the seriousness of the problem. Following a visit to the city by Premier Wen Jiabao in October, the State Council (China's cabinet) introduced a number of measures.

These included lowering the reserve requirement ratio specifically for small business lending so banks can lend more.

Other measures included tax concessions, including raising thresholds for when businesses have to pay various corporate and business taxes, and stamp duty relief.

The government said it would also boost the scale of specialized funds available to small businesses.

Some, including the Wenzhou Small and Medium-sized Business Development and Promotion Association, doubt whether these measures will provide the longer-term solution to the financing difficulties of the small business sector.

"The policies and measures introduced so far are to eradicate the crisis. What we need are more long-term reforms in terms of the structure of finance, taxation, investment, the availability of funding and a better administrative environment for small businesses," adds Zhou.

One of the big questions is how far the problems experienced in Wenzhou are indicative of a generalized funding crisis in China as a result of the government's credit-tightening policies.

Certainly, there are reports of problems in other entrepreneurial centers such as in Ordos in the Inner Mongolia autonomous region and Xiamen in Fujian province.

Joe Fuller, founder and chief executive of the Monitor Group, the global management consultancy, is one who believes it could put a brake on China's juggernaut economic growth.

"The absence of legitimate or regulated private lending to small- and medium-sized companies is a big threat to China's future growth," he said at the 10th China Entrepreneur Summit held by the China Entrepreneur magazine in late December.

"If the SMEs cannot get financing to develop their business, the growth will be damaged."

Simon Eckersley, founder and CEO of Hao Capital, a private equity company with offices in Beijing and Hong Kong, says, however, it is wrong to see Wenzhou's problems as being unique.

He cites the problems that Western SMEs currently have in getting loans from European and American banks still trying to restore their balance sheets in the aftermath of the economic crisis.

"I don't think it is a reflection of a broader problem of the Chinese economy because you also have it in Japan and in the UK," he says.

He says if businesses cannot demonstrate their competitiveness in any market at present, they are going to find it difficult to get money.

"This is the case in every country and every region. China's growth is maintaining its momentum, and the credit crisis in one region cannot reflect the whole picture."

What separates Wenzhou and China from many other countries is the level of non-bank private lending in the economy.

According to estimates by China's central bank, such lending could represent 4 trillion yuan ($632 billion, 487 billion euros) or 8 percent of all formal lending in the economy.

Much of this is dominated by people from Wenzhou. According to the forecasting organization IHS Global Insight, they have some 800 billion yuan of capital to issue as loans.

This sector is largely unregulated, consisting of consortia of small business owners and also private individuals sometimes lending to private individuals.

For many lending money at above-normal interest rates is a better investment than investing in equities or other financial schemes.

Over tea in the lobby of the Olympic Hotel in Minhang Road, Hu Zhenhua, professor of economics at Wenzhou University, paints a picture of the precariousness of this informal loans system.

"The whole system is based on A lending to B and B lending to C lending to D etc," he says.

"If D, however, flees the country, you get this domino effect where the whole system collapses. It is a crisis and it is probably getting worse."

The banks themselves claim there is plenty of money available for small businesses in Wenzhou and they themselves are not to be blamed for the funding crisis.

Wenzhou Bank, the largest local bank, lent 15.6 billion yuan in the first 11 months of 2011, a 17.5 percent increase on the 13.27 billion yuan of the whole of 2010.

Bad debts have increased from 0.87 percent of all loans at the beginning of 2011 to 1.03 percent by the end of November.

Pan Shifei, the bank's head of small business lending who cuts a youthful figure, was relaxed about the situation in his offices in Chezhan Road.

"No, I am not worried about it. The bad debts are way below the 3 percent we would regard as a warning sign. I don't think that is likely to happen," he says.

He adds it is not always straightforward lending to small businesses in the city because it is often difficult to assess the financial position of their businesses.

"There is often no clear dividing line between their personal and company accounts which makes it difficult to make lending decisions. Many also have little in the way of long-term planning and without planning it is easy to go bankrupt."

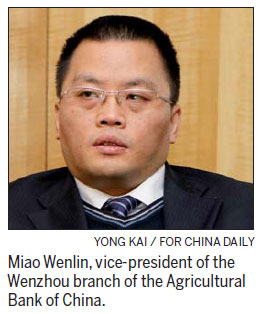

At Xiaonan Road in Wenzhou, Miao Wenlin, vice-president of the Wenzhou branch of the Agricultural Bank of China (ABC), one of China's Big Four banks, says the availability of bank loans is not the key reason for the funding crisis.

"The typical small business does not rely on bank finance. It is only when businesses aggressively expand that they become dependent on bank loans," he says.

ABC in Wenzhou issued 2,758 loans to SMEs in the first nine months of 2011 with an average value of 20 million yuan.

Miao says 80 percent of these loans were for either 6 months or 12 months and were for working capital, which he says is typical in Wenzhou. "Most small companies use it to boost their working capital. Those who borrow money to invest in technology or plant and machinery are rare."

Some believe the banks are not being completely open and are adding to the funding crisis.

Lu Peixin, executive director of Sunrise Capital, a private equity company, based in Wenzhou and Shanghai, says the bank statistics that show a growth in small business lending are misleading because they don't take into account other factors.

"Bank lending may have gone up because there has been a stronger need for SMEs to borrow from the bank since companies have had difficulty getting paid for their products from clients," he says.

"You also have to consider the costs have risen. Raw materials have gone up in price and wages in Wenzhou have gone up by as much as 20 percent. These are probably more to do with bank lending going up. So there is no real increase at all."

Since the crisis began to hit the headlines, the private lenders have been the ones that have often been demonized but that often ignores the important role they play in the economy, which even the mainstream banks admit.

"They are an important part of the financing system," says Miao at the Agricultural Bank of China.

"There are so many people taking part, including business people in a number of sectors as well as doctors, teachers and even public servants."

This begs the question as to how easy it will be to regulate, if the government does attempt to control the moneylenders.

Hu believes that the schemes proposed by the local government in Wenzhou to get small businesses to register all private loans will not work.

"They want to set up a private lending registration center but nobody will use it since there is no benefit to either the lender or the borrower since the local government is not acting as any form of guarantor," he says

"The actual characteristics of private lending are that it is hidden and basically free. It is also irreplaceable."

That it is irreplaceable is the essential problem as businesses try to steer their way through the Spring Festival period.

Many of them need the private lenders as well as the banks to start issuing new loans again - and fast.

|

Clockwise from top left: Pan Shifei, head of small business lending at Wenzhou Bank; Simon Eckersley, founder and CEO of private equity company Hao Capital; Hu Xucang, president and CEO of the Wenzhou-based private equity firm Aroundasia; Hu Zhenhua, professor of economics at Wenzhou University. Yong Kai / for China Daily Provided to China Daily Photos by Yong Kai / for China Daily |

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|