A family art

Updated: 2014-02-26 08:47

By Wang Qian and Ju Chuanjiang (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

Woodprint paintings are traditionally hung in homes around Spring Festival, but for the artists, creating the pictures is a yearlong activity and a lifetime of dedication. Wang Qian and Ju Chuanjiang report.

The Spring Festival has only just finished. But despite the festive celebrations having ceased for another year, a centuries-old folk art workshop in Yangjiabu village in Weifang, Shandong province, is still busy making Chinese traditional woodprint New Year paintings for customers.

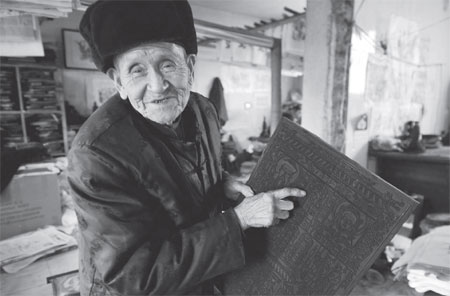

In a dusty, somewhat cramped, residence-cum-studio, Yang Luoshu, 88, successor of the family workshop named Tongshunde, prints pictures one at a time, using a big brush made of palm fibers.

He applies colors to the raised surfaces of a carved woodblock, places a piece of rice paper on it, then brushes it smooth to apply the first color. After several rounds, a picture of figures from the classic Chinese novel Outlaws of the Marsh begins to take shape.

Advanced in years, Yang has a hunched back, but he is still quick with his hands. In half an hour, he has finished a dozen paintings with delicate patterns and bright colors. "These paintings will be well bound and sent to a customer in Hong Kong who just ordered 1,000 copies," Yang says with a smile.

"It's been a family business for hundreds of years." As the 19th generation of a painting family, Yang learned the craft when he was 7. He was named a "master of folk arts" by UNESCO in 2001.

Together with 15 experienced craftsmen, Yang's workshop makes 150,000 New Year paintings every year.

Tongshunde is one of about 100 such family workshops flourishing in Yangjiabu village.

With 300 families, Yangjiabu has been making woodblock-printed New Year paintings since the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). It is now one of China's three production centers of traditional folk paintings, together with Tianjin's Yangliuqing and Suzhou's Taohuawu.

Local government records show that the village can produce 210 million single-sheet prints a year, which are sold across the nation and to countries such as Russia, Japan, South Korea and Singapore.

These paintings are no longer mere decorations for the Spring Festival, they are also fine works of art sought by international collectors.

"However, compared with the village's heyday 200 years ago, when nearly 300 workshops and stores flourished, the figure today is very small," says Wang Yonghai, head of the Weifang municipal research institute on Yangjiabu New Year paintings.

Chinese people tend to decorate their homes with New Year paintings during the Spring Festival, to ward off evil spirits and bring good luck to the family throughout the whole year.

The origin of New Year paintings can be traced back to the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907). The legend goes that Li Shimin, the second emperor of the Tang Dynasty, often had nightmares about ghosts. Then he asked an artist to paint portraits of his two bravest generals and paste them on to the door to guard him through the night, and his nightmares stopped.

The artist who painted for the emperor is said to come from Yangjiabu. When he returned to his hometown, many people asked him to make the same painting, and so "door gods" were created, and are still the most common subjects of Yangjiabu New Year paintings.

The themes of Yangjiabu paintings cover a wide range of topics, from folk religion, auspicious symbols, historical personages, myths and legends, to current affairs, local customs and landscapes.

"They are all based on the lives of the people and sometimes are also used to express various sentiments," Wang says.

A typical painting once widespread during the Ming Dynasty, for example, portrays the story of Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang, founder of the dynasty, showing his ministers how to plow the fields. The picture was trying to persuade the emperor to stop his despotic rule and develop production.

"Yangjiabu painting stands out with its rich use of bright color, rough lines, exaggerated images, and full composition. It is pure and down-to-earth, and it is especially favored among the Chinese public," says Wang.

There is an old saying that during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), each family in Yangjiabu had a painting workshop, and everybody was good at the handicraft, he says.

The custom is particularly popular in the countryside, where colorful paintings remain the dominant decorations on doors, windows, walls and even on wardrobes and stoves throughout the year.

"However, with the invasion of modern production methods, traditional printing techniques have been challenged and few young people have enough patience to learn the craft," says Zhang Dianying, a local well-known folk artist and vice-president of China Woodprint New Year Painting Association.

"Making a Yangjiabu New Year painting generally requires at least 10 steps, ranging from sketching outlines, engraving the woodblock, printing and painting to mounting. All of them have to be completed by hand," the 78-year-old explains.

"The most difficult step is the carving. One wooden board needs to be engraved for one kind of color. To master such a skill requires years of experience," says Zhang, whose palms show signs of wear, dyed yellow with thick calluses.

To show the versatility of the art form, Zhang spent four years engraving a total of 531 woodblocks and creating a 32-meter-long painting. Named The Happiness of Chinese Farmers, it vividly depicts more than 1,000 characters and 100 scenes. It is said to be the nation's largest woodblock-printed painting and is part of the collection of the National Museum of China.

"My work is a piece of art, which cannot be achieved by machines," he says with great pride.

Meanwhile, Zhang's much-younger peers at a local culture and art company are committed to breathing new life into the traditional art form.

"We are attempting to renew the motifs and forms of traditional Yangjiabu New Year paintings through combining diversified art styles, to cater to modern tastes," says 39-year-old Yang Zhibin, an artist with Weifang Fengtai Culture and Art Co.

One of his bold inventions is combining the traditional craft with the styles of modern oil and watercolor painting, bringing a modern touch to the folk art.

The local government has also taken a range of measures to popularize the art in recent years. A 146,000-square-meter folk art garden has been established in Yangjiabu, where tourists can see not only rural people's residences with touches of the Ming and Qing dynasties, but also see how New Year paintings are made.

"We invite tourists to come and buy our paintings. The number of visitors has grown to 800,000 annually from 20,000 in the 1990s," says Yang Gaozhi, head of the Yangjiabu village.

Professional courses have been set up in several local primary and middle schools to train new artists and foster young people's interest in the traditional art form.

Contact the writers through wangqian2@chinadaily.com.cn.

|

Yang Luoshu, 88, the 19th generation of a Yangjiabu New Year painting family, shows off an ancestral woodblock of his family's dating back to the Ming Dynasty. Photos by Ju Chuanjiang / China Daily |

|

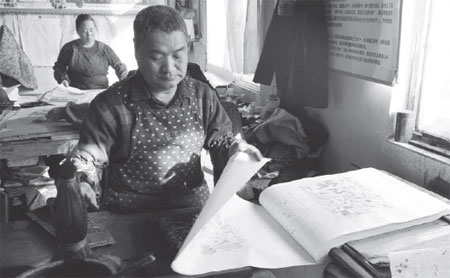

Villagers work at their family New Year painting workshop in Yangjiabu village, Weifang, Shandong province. |

|

A Yangjiabu New Year painting features four children ushering in a prosperous happy New Year. |

(China Daily 02/26/2014 page20)

Today's Top News

Turks stage protests demand PM's resignation

Forecast:China to lower growth rate

Italian new govt wins vote of confidence

Ukraine enters uncharted water

Li urges stronger S. China Sea ties

Fight against graft faces challenge

Ukraine sets back on European course

Chinese pandas arrive in Belgium

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|